WACO—When many readers describe the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, the word “majesty” tends to enter the conversation.

It’s no wonder, according to Laura Knoppers, professor of English at Penn State University.

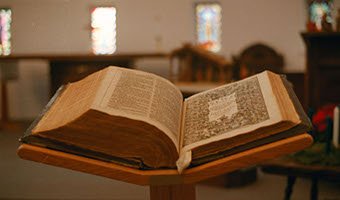

The Dort Bible, a rare second-edition of the Authorized King James Bible, was published in 1613. (RNS PHOTO/Pablo Richard Fernandez)

|

The translators King James enlisted to create a new version of the English Bible had an agenda—to provide scriptural support for the divine right of kings, she asserted.

But Protestant dissidents such as John Milton, in turn, used the same language the translators appropriated to emphasize democratic principles, she observed.

Knoppers examined different views on the term “majesty” in her presentation to a convocation sponsored by Baylor University and its Institute for Studies of Religion that marked the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible.

When nonconformists brought a list of grievances to King James at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, James later boasted he “peppered the Puritans soundly” and turned aside nearly all their demands. However, for his own reasons, he embraced their desire for a new English-language translation of the Bible.

A uniform translation could unify the English-speaking people of Great Britain, James reasoned. Also, the king realized, he could use the translation to shore up the Anglican Church and “amend and polish what was amiss” in existing English translations.

For the most part, the translators employed a variety of English words to express a single Hebrew or Greek word.

“One important exception was the reiterated word ‘majesty,’” Knoppers observed. In that case, the translators reversed normal procedure and applied that single English word to multiple words in the original biblical languages. The word “majesty” is used 72 times in the text, headings and notes of the King James Bible and 18 times in the opening dedication and preface, Knoppers discovered.

“Use of the word ‘majesty’ linked the earthly monarch with God himself,” she concluded. The translation blurred distinctions between the attributes of God and attributes of the earthly king.

However, in both his polemical writing and his epic poetry, Milton took the opposite ap-proach—stripping majesty from the office of the king and portraying it as resting upon the people at large.

“For Milton, the emphasis was on the power and dignity of the people” rather than the monarch, Knoppers said.

In Paradise Lost, Satan seeks to claim as his own majesty that rightly be-longs to God and to the couple in the garden created in God’s image—a metaphor for “kingly usurpation of divine majesty,” Knoppers ex-plained.

“Milton dramatizes the danger of usurping the characteristics of God,” she said.