People of faith must measure the truthfulness of what they hear and see during an election year — and they must be especially careful about the information they pass along.

Believers should weigh information they glean or that they receive from others. What is the source? Is that person trustworthy? From how many sources did it come?

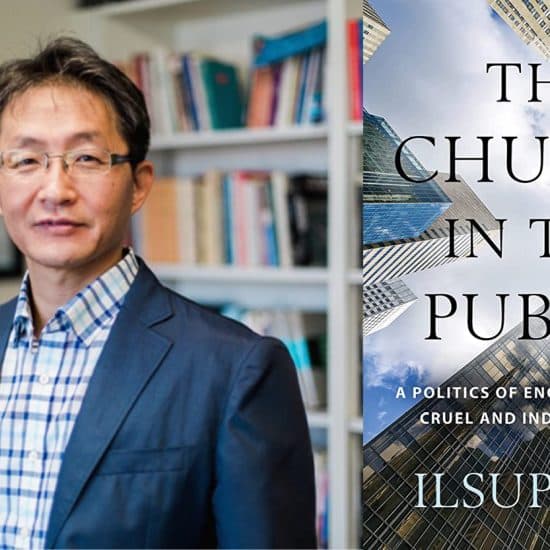

"It requires work in this day and age to take mediated information and make a cohesive whole," noted Lee Wilkins, a University of Missouri broadcast journalism professor who also teaches ethics.

"Information is trustworthy essentially if you're getting the same thing from multiple sources…as long as they are independent of one another," she said.

"Consumers need to be careful not to blur information [that's written] for information or for persuasion."

Direct mail from the candidates themselves tends to be persuasive, Wilkins emphasized. "People are getting…more information from the 'Net…. You must understand the originator of the information and if it is attempting to inform or to persuade," she said.

Kyle Kondik, a political analyst for Sabato's Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia Center for Politics, agreed. Voters must be aware that candidates sometimes stretch the truth "to make themselves look good and their opponents look bad. Complicating matters is that, with some ads, it's almost impossible for voters to determine who is responsible for a specific ad," he said.

"Political action committees… might have flowery, meaningless names that tell voters nothing about who they actually support," he added. He pointed out that "Restore Our Future" is a Super PAC that supports Mitt Romney, while another, "Winning Our Future," supports Newt Gingrich.

"Not only are these names effectively meaningless, but they are so similar that it's hard even for people who closely follow politics to tell them apart. In order to get a more accurate view of what's going on, voters should probably pay attention to people or news outlets that they know and trust," Kondik said.

Because a great deal of the information about candidates and their stands is drawn from sometimes not-so-trustworthy sources, people of faith must be careful about passing it to others.

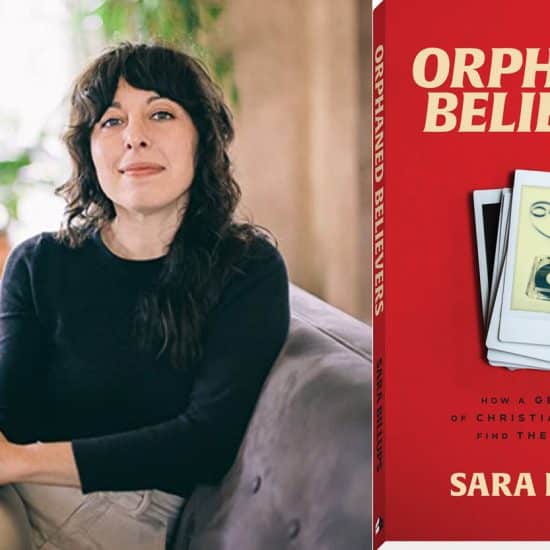

They also must make certain that they aren't simply passing along their own interpretation of the information they've found. Too often, "Christians latch onto one issue at the exclusion of everything else," Van Christian, pastor of First Baptist Church in Comanche, Texas, said.

"We are horrendously guilty of the urban legend syndrome. If it sounds good to us and seems plausible, we want to warn everybody about it," he added.

Even if the information comes from those closest to a believer, he or she must still test it. "If you have family and friends and other people in your circle…whom you trust…still check it out…," Wilkins said. "We all have our filters…but we can all think for ourselves, independent of government…and of other powerful forces in our lives, whether…a teacher or a cleric. As Americans, we get riled up when a Muslim cleric tells a group what to do…but we tend to look at that differently when it's close to home….

"People should be able to respond to information with the question: How do you know that?"

Test the truthfulness of any political information.

|

Christian recognizes that believers often pass along information to help others but he suggests thinking before sharing it. "If we were discussing politics with Jesus, would we do it the same way we do with others?" he asked.

With additional reporting by Ken Camp