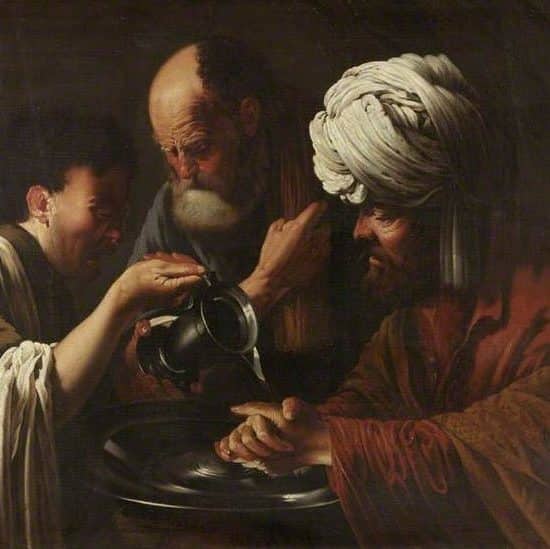

In biblical times, priests offered animal and grain sacrifices — as thanksgiving or to seek forgiveness for sin. Sacrifice meant death. But in Romans 12:1, the Apostle Paul called on believers to be “living sacrifices.”

How does a believer live, yet sacrifice to please God? What does it mean for a Christian to sacrifice in contemporary times? Do believers live sacrificially both individually and as the church?

Living Sacrifice

|

For Roger Olson, the Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology and Ethics at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas, living sacrificially means living for others. In other words, believers “die” to self or sacrifice their desires to put the needs of others first.

Not just any “other,” though. Olson believes Christians must care first for those who need help most. “The mark of such a (sacrificial) life is eager willingness to give up comfort and privilege when that will help the weak,” he said.

When he considers organizations such as Voice of the Martyrs, a nonprofit organization that tracks believers persecuted for their faith, Richard Menninger acknowledged: “I don’t sacrifice. I really don’t.”

Menninger, the Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion and chair of the department of theological and religious studies at Ottawa University in Ottawa, Kan., believes Christians must be logical and intentional about sacrificing their entire being to the Lord. “Everything we do or think should be offered to God…to bring him glory and honor,” he said.

That action, he said, plays out in common ways, as The Message version translates Romans 12:1: “Take your everyday, ordinary life — your sleeping, eating, going-to-work, and walking-around life — and place it before God as an offering.”

Sometimes sacrifice means ordinary things, such as giving up being politically correct or giving up the safety of not saying anything or making life simpler in order to be free to serve others, he explained.

Menninger believes a common application of sacrificial living often is the “willingness to deal with and be available to people with whom I disagree,” he said, even “to live with and worship with” them.

Sacrificial living, then, involves an intentional choice. “Intent seems to matter as to whether or not an action is truly…sacrificial,” noted Tarris Rosell, the Rosemary Flanigan Chair for the Center for Practical Bioethics, professor of pastoral theology in ethics and ministry praxis at Central Baptist Theological Seminary and a clinical associate professor of the history and philosophy of medicine for the University of Kansas Medical Center School of Medicine.

“Do I intend my action to be one that benefits others at personal expense? Or does it just happen that I end up in such a situation without having intended it? Intent matters, surely.”

Choice, too, determines whether an action could be considered sacrificial. “If I do not choose my situation of loss so that others might gain, but merely find myself there, is that sacrifice? No. It might be misfortune, but that is not sacrifice,” Rosell added.

The concept of sacrifice might change based upon life circumstances, he observed. A single person might choose to live in a depressed urban neighborhood and volunteer to meet needs. A married couple might choose a suburban community because of their children. They may give a percentage of their income to the church or charities, rather than using it to purchase a nicer car or a vacation home. Older individuals might consider giving up an opportunity to move to a retirement home to remain an influence in their grandchildren’s lives as a sacrifice.

The distinction would have to be made between the believer and God. “But I’m not sure whether any of that counts as meaningful sacrifice,” Rosell pointed out. “It might be something more like ‘minimally charitable.’”

Romans 12:1 presents a call to the whole church as community and to individuals as members of the body, Elizabeth Newman explained. “I think living sacrificially has often been interpreted — at least in our contemporary culture — as primarily an individual effort,” said Newman, the Eula Mae and John Baugh Professor of Theology and Ethics at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond (Va.).

She pointed out the Apostle Paul also called believers to renew their minds. “So renewal and sacrifice are deeply intertwined, and both are communal practices. The Spirit works through our brothers and sisters, through the preached word, through the sacraments to renew us, to give us new life,” she said.

“From this perspective, our bodies — our selves — are not simply ours, but are gifts from the God who heals us. To truly see this reality is to offer ourselves back to God in a sacrifice of thanksgiving and praise. To live sacrificially is to live abundantly.”

The corporate body should be sacrificial, as well, Olson agreed. Each congregation must be willing to give up “its own comfort” for “those…who are weak and in need,” he said.

Church members first must recognize when they have put congregational needs ahead of sacrifice. “A congregation might be sacrificial when they vote to raise mission giving to 15 percent of (its) annual budget, or when using endowment earnings to support a shelter downtown rather than updating the 1980s decor of their fellowship hall,” Rosell said.

Menninger added Christians must be willing to ask themselves some hard questions: “Are there people in the church that don’t feel accepted? Is all our money going to the church? Are we involved in the community?”

Sacrifice, he insisted, must center on constantly asking the self, both individually and corporately: “Why am I doing what I’m doing? Am I willing to give up what I’m doing for others?” Living sacrificially is “an act and a process.”

Menninger concludes the believer’s relationship with people should be the measure of sacrificial living. Consciously “tithing” all of life’s aspects to God, making every day a sacrifice and bringing glory to the Lord in everything “results in more peace, more concern about people than things or activity,” he said.

“But you are not living a life of sacrifice if things and deadlines become more important than people.”