February is Black History Month, also known as African-American History Month. It is a fitting month for Americans — all Americans — to observe this time and catch up on this aspect of America’s rich heritage.

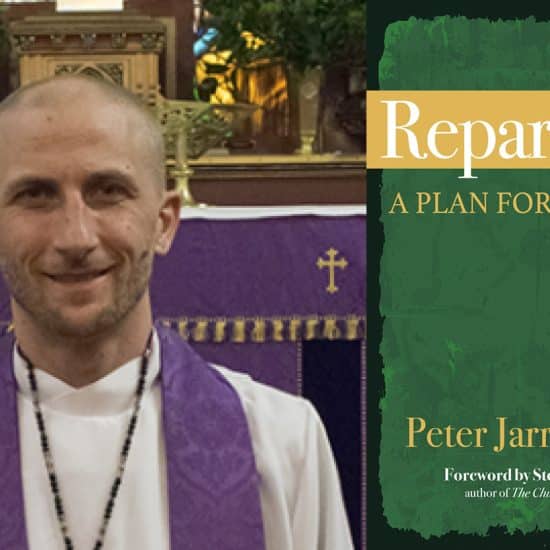

Bill Webb

|

During the past year, Americans observed the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, a pivotal event in the Civil Rights Movement in America. Commemorations of historical events give us greater motivation to see where we have been and measure our progress since.

The study of history is a “warts and all” endeavor. Accurate and reliable history not only logs accomplishments of people and groups of people, it takes note of disappointments and even atrocities they either inflict or experience at the hands of others. Because history recounts the good, the bad and the ugly in the lives of humankind, it is imperative that we explore the subject critically, sometimes to the point of discovering intentionally hidden truth.

Only a few generations ago, the history of African Americans and their accomplishments were, at best, footnotes in written histories of America. If mentioned at all in history books, they were digested to the point of being severely minimized or easily overlooked.

The United States is a highly pluralistic nation today, with people from virtually every corner of the earth and every culture. Many have not been treated well in their pursuits in the Land of Opportunity, yet many of them have made lasting positive contributions to the American nation. “Why not single them out for a special month?” some would ask.

The history of various minority groups in our country and their contributions ought not to be ignored, of course.

But because history has demonstrated that the nation has been snail-like in granting basic personhood and a measure of equality to people of African descent, it is fitting for African Americans and all Americans to get up to speed on this critical subject.

African-American friends tell us we are not there yet in ensuring equality for all.

The church has moved slowly on this subject, too. Martin Luther King Jr. referred to the time of worship on Sunday mornings as the most segregated hour among Christians in America. If he were alive today, Dr. King’s assessment might not be very different in 2014. Because of him and others, churches and Christian people have made at least a measure of progress. Many have done better than others, of course.

A good starting point for observing this month of African-American history would be to explore the contributions of our fellow citizens past and present by exploring distant and present-day history. We do it best when we take the long look, tracing the story from America’s earliest beginnings.

For instance, when adults begin to better understand the wrongness of human bondage, they find themselves in a better position to understand the magnitude of accomplishment for people who for generations in the 20th century were denied education or at least denied education of the quality of others and even the right to vote.

Textbooks do better at being more racially inclusive these days but parents and grandparents should use this point in time to re-educate themselves and tell the stories of black accomplishments in politics, business and enterprise, education, the arts, athletics and a host of other areas. There really are no limits.

Young people tend to reflect the adults they love and admire in their own attitudes about racial differences. They say the same things their parents say about people who are different — for good or bad. And adults can’t fully hide who they are when it comes to disrespectful racial attitudes. We can ask children to “do as I say, not as I do.” If it were only that easy!

The best teachers live out what they are trying to communicate. They have good relationships with people who are different, no matter what the color or what the culture. They sometimes acknowledge disagreements in points of view, but they gracefully demonstrate respect in their differences. They admire the courage and accomplishments of those who have persevered against considerable odds to achieve.

I have frequently told the story of briefly meeting a famous African-American entertainer on an elevator about 20 years ago. We were staying in the same hotel, I to attend an annual Baptist meeting and she to star at a jazz festival in the same city. We rode the same elevator down and, an hour later, rode it back up to our rooms.

Before we boarded the same elevator, I sheepishly asked her what I already knew, “Are you Ella Fitzgerald?” She was, she admitted, and began to visit. What I discovered was that Ms. Fitzgerald wasn’t just a famous singer, she was an engaging person. And she was not just that but a real lady. She represented herself and her race — the human race — very capably. Ella Fitzgerald died a few years later, but I keep telling people about this remarkable woman of color who showed an interest and was willing to talk with me. Honestly, I don’t remember much about the three-day meeting I attended, but I’ll never forget her.

Bill Webb is editor of Word&Way.