When the nation divided during the Civil War, Missouri found itself tugged in both directions. A ‘border state,’ the government actually split with competing governors — one favoring the North and another favoring the South. In the decades surrounding the Civil War, many other American institutions fractured along North-South lines. Not even churches were exempt. Baptists, Presbyterians and Methodists all split regionally over slavery.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Baptists in Missouri experimented with a unique model of dual alignment with both Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) and Northern Baptist Convention (NBC, now American Baptist Churches, USA). The Missouri Baptist General Association (MBGA; now known as the Missouri Baptist Convention) started in 1834 and sided with the SBC following the North-South split in 1845, but some churches in the state still supported Northern Baptist missions.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Baptists in Missouri experimented with a unique model of dual alignment with both Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) and Northern Baptist Convention (NBC, now American Baptist Churches, USA). The Missouri Baptist General Association (MBGA; now known as the Missouri Baptist Convention) started in 1834 and sided with the SBC following the North-South split in 1845, but some churches in the state still supported Northern Baptist missions.

After the War, the Missouri Plan emerged that connected the MBGA with both the SBC and NBC. The Missouri Plan allowed a church to give its missions money entirely to one national body or to leave it undesignated so it would be divided according to a formula based on the state’s previous support of the various missions agencies. Leaders from Southern and Northern Baptist churches served in MBGA positions.

Adrian Lamkin, an American Baptist leader in Illinois, sees that period of dual alignment as an important but under-appreciated period of Baptist life. Lamkin previously served as director of the William E. Partee Center for Baptist Historical Studies at William Jewell College in Missouri and later as a Baptist history professor at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.

“The Missouri Plan really came into being in those years after the Civil War,” Lamkin said, though he noted it took years to fully emerge.

The first steps came as Baptists in the state reunited in the late 1860s after the brief existence of a second state convention that favored Northern Baptists. Lamkin noted Missouri Baptists sought ways to work together despite differences and to increase efficiency. Some also thought the Northern and Southern conventions might reunite. In 1889, they launched the Missouri Plan.

“One of the reasons that Missouri Baptists were going to the Missouri Plan was some of them had the idea that maybe by bridging that issue and coming together now and working together they hoped it would be a model for other Southern Baptists and Baptists in the North,” Lamkin noted.

“There were some Missouri Baptists that thought if we push the Missouri Plan — we are neither North or South, we are both — maybe it will be a model for other Baptists on how we can come back together,” he added. “The Missouri Plan was really an effort to say, ‘How can Baptists of different views work together?’”

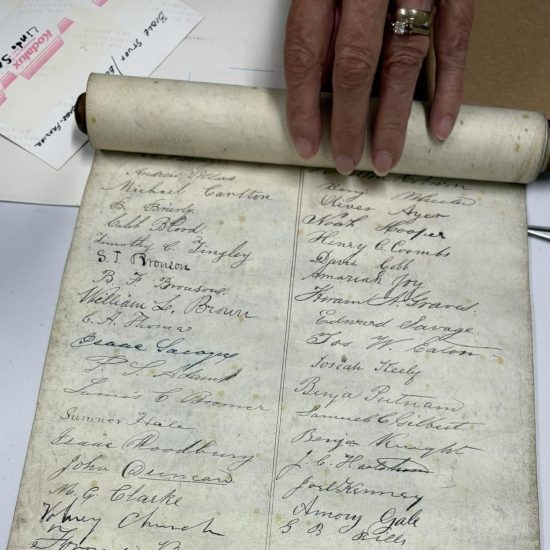

Baptists at the time saw the Missouri Plan as a revolutionary step in Baptist cooperation. E. W. Stephens, then-board president of the General Home and Foreign Missions of the Missouri Baptist General Association, reflected on the start of the Missouri Plan in 1889. He praised Missouri Baptists for putting aside “the spirit of sectionalism” that previously “menaced harmony and prosperity.”

“The Missouri Plan has attracted the attention of the country, and its success may yet effect an innovation in missionary methods, North and South,” he said. “The most gratifying experience has been the favor with which it has been received by churches.”

“The Missouri Plan appeals with a special force to every Missouri Baptist,” he added. “It means a unification of our missionary work, a closer sympathy between the churches, a burial of sectional bitterness and an undoubted impetus to the mission cause.”

Stephens later credited the Missouri Plan with increased missions contributions and for having “established a unity and brotherliness that have excited the admiration of the entire land and exercised an influence far beyond the borders of Missouri.”

Lamkin believes the Missouri Plan should still inspire Baptists today. He acknowledged, however, it might be “much more difficult” today to see something like the Missouri Plan given years of lawsuits, tensions, divisions and harsh rhetoric.

“There is that need for us to think again how can we work together,” he said. “The Missouri Plan was a way to think how we can cooperate together for the Lord’s kingdom.”

Dually-aligned churches

The Missouri Plan started to fall apart in the 1910s, with it ending in 1915 and the MBGA deciding to singularly-align with the SBC in 1919. Churches in the convention were still allowed to dually align until 2006. In the decades following the collapse of the Missouri Plan, several churches sporadically dropped one of their alignments.

While many went with the SBC, a few — like Bethel Baptist Church in Columbia in 1967 — chose American Baptists. Today, a few churches still maintain a historic dual alignment, including Dayspring Baptist Church in St. Louis, First Baptist Church in Columbia, Third Baptist Church in St. Louis and University Heights Baptist Church in Springfield.

Danny Chisholm, senior pastor of University Heights Baptist Church, noted the church has been dually aligned since its founding. While that relationship started as one with ABC and SBC, the church now relates to the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and ABC. Chisholm added that “University Heights wanted to retain an amicable relationship with Southern Baptists” so the church remains connected with local Southern Baptists as part of the Greene County Baptist Association even after the MBC kicked the church out over a new single-alignment policy in 2006.

“We appreciate being part of a broader community of faith,” Chisholm said about being aligned with various Baptist bodies. “We relate with them and we want to cooperate.”

“I think being dually aligned is an effort to try and accommodate different type of viewpoints in your own church,” he added. “It’s been a good situation. There hasn’t been any type of friction or conflict, and I’m very grateful for that.”

Chisholm noted University Heights includes both ABC and CBF in the budget and promotes the missions efforts of both groups. The church also includes budget support for several Missouri Baptist institutions. He hopes this model could inspire other churches to have “space made available for people” who may wish to work with a Baptist body other than the church’s main affiliation.

“Look at it as more of a cooperation rather than a competition,” he added.

See also:

Learning from the spirit of the Missouri Plan

Revive the spirit of the Missouri Plan