The smell of old pizza lingered in the crowded room.

The hearing room in the basement of the Missouri Capitol building swelled beyond capacity with each seat claimed and every spot where someone could stand filled. The seats reserved for the state legislators remained vacant. Long after the hearing’s posted started time that Tuesday night in April, the legislators still had not appeared.

A hearing room in the Missouri Capitol is filled to overflowing for testimony on a religious liberty bill, SRJ 39.People looked around, made small talk and stared at the slowly-moving hands on the clock. Some impatiently gathered around phones and iPads watching for updates as legislators debated various bills two stories above the crowded room. A few legislators showed up to provide free pizza for everyone as the delays pushed the hearing start past suppertime.

A hearing room in the Missouri Capitol is filled to overflowing for testimony on a religious liberty bill, SRJ 39.People looked around, made small talk and stared at the slowly-moving hands on the clock. Some impatiently gathered around phones and iPads watching for updates as legislators debated various bills two stories above the crowded room. A few legislators showed up to provide free pizza for everyone as the delays pushed the hearing start past suppertime.

Shortly after eight that evening — more than three hours after the planned start — three bangs of a gavel opened the House Emerging Issues Committee hearing. With the room overflowing into the hallway, officials opened up a second room and broadcast the hearing live for others to watch on a screen.

Even before the packed hearing, the bill on the docket emerged as the most controversial and high-profile bill of the legislative session.

When brought to the Senate floor a month earlier, it sparked a record 39-hour filibuster. Missouri’s longest filibuster ever only ended after proponents used a rare parliamentary procedure to force a vote.

Joining the legislators and people hoping to testify in the House committee were numerous media outlets and even other legislators not on the committee who chose to stand against the back wall instead of heading to supper.

After more than four hours of back-and-forth arguments, the committee’s chairman allowed staff and others to head home. Then, in an unusual — if not unprecedented — act, the chairman and several other committee members stayed to hear more people still waiting to testify. They finally wrapped up things around 1 a.m. the next morning.

The theatrics did not end that night. The chairman postponed the committee’s planned vote on the bill the next week as some legislators struggled with how to vote. A week later, three Republicans joined the three Democrats on the committee to vote against the bill and kill it for this year. The deciding vote turned out to be Republican Representative Jim Hansen, a Baptist, who teared up as he announced his vote against the bill.

What brought so much attention and politicking? A bill on religious liberty issues.

The debate

Known as “SJR 39,” the bill proposed a state constitutional amendment to carve out legal protections for business owners and others with religious objections to same-sex marriage. If passed by state legislators, the proposed amendment would have gone to Missouri voters for consideration.

The debate quickly appeared to pit several Christian leaders and their lawyers on one side and leaders from the business and LGBT communities on the other side.

Multiple Missouri Baptists testified that night. Michael Whitehead, the Missouri Baptist Convention’s chief legal counsel, stepped forward as the first witness for the bill.

“The fullness of this room actually shows this is a very important issue to the citizens of the state of Missouri,” he said. “I want you to know the sense of urgency that we have that if this body does not vote without amendments, this will die this year [and] the people won’t have a chance to vote.”

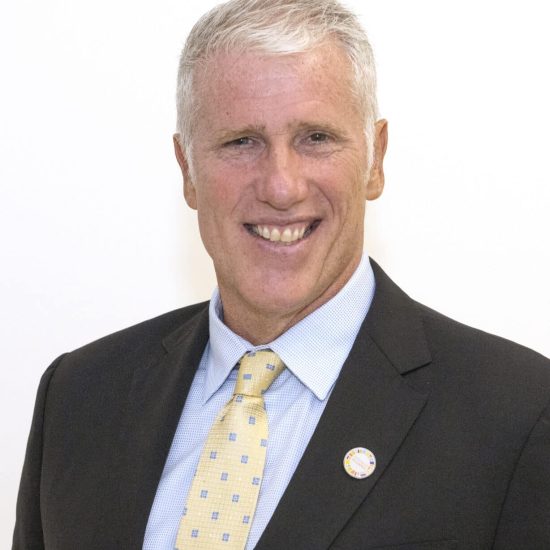

A few speakers later, Don Hinkle walked to the hearing microphone. The MBC’s director of public policy, Hinkle served as a key figure in drafting and promoting the bill. Early meetings to craft the legislation occurred at the MBC’s building down the street.

Both Whitehead and Hinkle argued people in the wedding industry who religiously disagree with same-sex marriage should be allowed to deny services to same-sex couples. They claimed without SJR 39, Baptists and others would face discrimination.

“When it comes to discrimination, Baptists know all about it,” Hinkle said as he noted he spoke “on behalf of the 2,000 churches and the 600,000 members of the Missouri Baptist Convention.”

Jonathan Whitehead, another MBC attorney, also testified for SJR 39. Additional speakers for the bill included a Missouri University School of Law professor, a nondenominational pastor from St. Joseph and Lt. Governor Peter Kinder.

Currently running for governor, Kinder quoted from the man whose statue stands guard outside the Capitol — Thomas Jefferson. Kinder claimed the quote came from Jefferson’s “famous letter to the Danbury Baptist Association.”

Witnesses against SJR 39 included leaders from the Missouri Chamber of Commerce, Kansas City Convention & Visitors Association, Kansas City Sports Commission and American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri. After multiple Christian representatives testified for the bill, one minister rose to oppose it.

From Word & Way Editor Bill Webb:

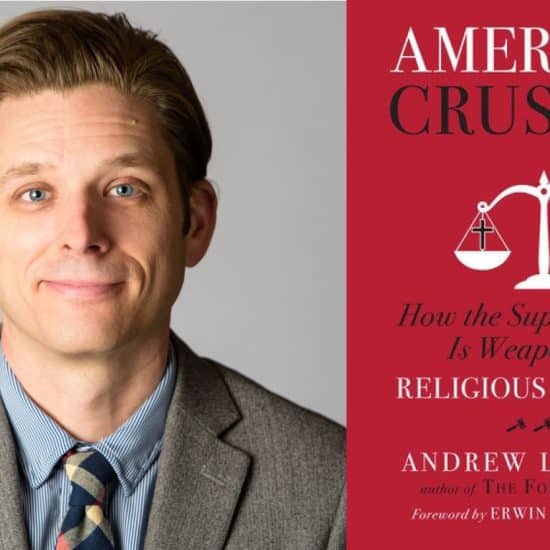

Knowing Brian Kaylor, the author of our cover package on religious liberty, who also serves as Churchnet’s generational engagement team leader, was the minister who spoke against SJR 39, I requested a text of his testimony. Following is a portion of what he said:

“Missourians already enjoy strong religious liberty protections. Those claiming we need additional religious liberty legislation demonstrate they do not believe or trust in the U.S. Constitution, Missouri Constitution and Missouri’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act. I instead have faith in the historic religious liberty protections that have served us well.

“True religious liberty must be for all.

“SJR 39 wrongly privileges one religious belief over others. To allow the state to choose winners and losers among religious beliefs yields the government too much power.

“Thomas Helwys, one of the first Baptist leaders, in 1612 wrote the first English book calling for religious liberty for all people (as opposed to the usual argument of people just demanding freedoms for their own people).

“Early Baptists in the U.S. like Roger Williams and Isaac Backus preached this message of religious liberty for all. Thomas Jefferson’s usage of the phrase ‘wall of separation between church and state’ came in a letter to Baptists in Connecticut because he knew the Baptists would appreciate that philosophy. Were it not for the tireless advocacy of Baptist preacher John Leland, the religious freedoms in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution might not exist.”

See also:

Baptists advocate for religious liberty in D.C. and around the globe