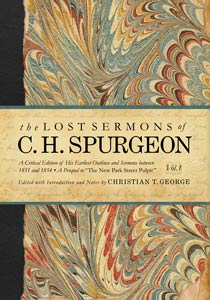

In February, B&H Academic — a division of the Southern Baptist Convention’s publishing house — released the first in a 12-volume set of “The Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon.” The books are edited by Christian George, who found the sermons a few years ago. George serves as curator of The Spurgeon Library and assistant professor of historical theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri. Word&Way Editor Brian Kaylor interviewed George about the new volumes of Spurgeon sermons. Learn more about Spurgeon and The Spurgeon Library at spurgeon.org. This is an expanded version of the interview with sections in italics below not included in the print magazine.

Your newest book is an edited volume of ‘lost sermons’ of famed 19th Century English Baptist preacher C. H. Spurgeon. How did you find these sermons and what was that moment like?

Christian GeorgeIn 2011, as I was preparing to defend my Ph.D. dissertation, I encountered a stack of handwritten notebooks in London that contained the earliest sermons of Charles Spurgeon. For approximately 160 years, these sermons have been lost to publishing history. In 1857, Spurgeon tried to publish these sermons himself, but the demands of his new pastorate prevented him from doing so. As I held the stack of notebooks in my hand, my initial impulse was to fulfill Spurgeon’s long-lost dream. I remember looking over at my wife, Rebecca, who was with me at the time and telling her with trembling hands that by the grace of God we must finish the project Spurgeon had started. Since that moment six years ago, the road to publication has been anything but smooth. Numerous publishing houses turned down the project because of its enormous size: the whole twelve volumes will be about one million words.

Christian GeorgeIn 2011, as I was preparing to defend my Ph.D. dissertation, I encountered a stack of handwritten notebooks in London that contained the earliest sermons of Charles Spurgeon. For approximately 160 years, these sermons have been lost to publishing history. In 1857, Spurgeon tried to publish these sermons himself, but the demands of his new pastorate prevented him from doing so. As I held the stack of notebooks in my hand, my initial impulse was to fulfill Spurgeon’s long-lost dream. I remember looking over at my wife, Rebecca, who was with me at the time and telling her with trembling hands that by the grace of God we must finish the project Spurgeon had started. Since that moment six years ago, the road to publication has been anything but smooth. Numerous publishing houses turned down the project because of its enormous size: the whole twelve volumes will be about one million words.

The lowest point in this project was in 2013 when my health failed. After suffering from ulcerative colitis for twelve years, my appendix ruptured at the beginning of January. I didn’t find out for about a full month. The surgeon said I was lucky to be alive. Over the next twelve months, I underwent three life-threatening surgeries while teaching as a professor at Oklahoma Baptist University. After my final surgery, I almost lost hope of finding a publisher. Rejections were plenty. Then out of the blue, B&H Academic called me and told me they wanted to publish the sermons. One month later, Dr. Jason Allen, President of Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Mo., called me and invited me to consider teaching at the seminary and curating The Spurgeon Library. From that day onwards, the project — like my own life — was revived. Today, God has given me an amazing team of student researchers who have labored alongside us to publish these lost sermons. I am continually reminded that a thousand gears of grace have rotated across a century and a sea to make this project possible. All glory goes to God.

The project is a labor of scholarship, but it’s also a labor of love. We wanted to present these sermons in a way that both the academy and the church could access. And to make it beautiful. We hired a professional artist to hand-marble the covers in the style of the original notebooks. We included full-color facsimiles of every one of the 6,000 handwritten pages, along with transcriptions, editorial commentary and a contextual/biographical introduction. “The Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon” will add approximately ten percent of material to Spurgeon’s total body of literature and will constitute the first critical edition of any of his works.

Since these sermons come from the earliest part of Spurgeon’s ministry, how do these texts show signs of changes in his style or theology when compared to later, more well-known works of Spurgeon?

That’s one question I have been asking also. And these also: What influences shaped Spurgeon’s earliest ministry? What mistakes did he make? Did Spurgeon’s theology, preaching style, or doctrinal emphases change or remain constant? Spurgeon’s first notebook of sermons contains his literary productions, beginning with only the fourth sermon Spurgeon ever preached. Spurgeon is a brand-new convert preaching only months after his conversion in the snowstorm of January 1850. At first, Spurgeon writes one-page outlines. He called them “Skeletons.” But over the course of the notebooks, his sermons become longer in length. By Notebook 9, his sermons are fifteen pages in length. That is the only time in his whole ministry he ever fully manuscripted his messages. So the evolution of his style is a unique discovery in itself.

That’s one question I have been asking also. And these also: What influences shaped Spurgeon’s earliest ministry? What mistakes did he make? Did Spurgeon’s theology, preaching style, or doctrinal emphases change or remain constant? Spurgeon’s first notebook of sermons contains his literary productions, beginning with only the fourth sermon Spurgeon ever preached. Spurgeon is a brand-new convert preaching only months after his conversion in the snowstorm of January 1850. At first, Spurgeon writes one-page outlines. He called them “Skeletons.” But over the course of the notebooks, his sermons become longer in length. By Notebook 9, his sermons are fifteen pages in length. That is the only time in his whole ministry he ever fully manuscripted his messages. So the evolution of his style is a unique discovery in itself.

Only a few years after these sermons were preached, Spurgeon became the world’s most popular preacher. In fact, by the time he’s twenty years old, a New York biography of his life put him on the global radar. How did Spurgeon go from being a poor, formally uneducated teenage preacher to commanding the attention of kings, queens, and presidents What were his influences? Or, you may say, how did Spurgeon become Spurgeon? One answer to that question is hard work. Spurgeon often preached ten to twelve times per week. So he’s not Netflixing his days away, so to speak. He’s also reading the best writers, thinkers, and theologians England had produced. He’s reading John Bunyan, Richard Baxter, George Whitefield and many others. He’s also memorizing long passages of Shakespeare and other masters of the English language. Thanks to his uncanny photographic memory, he never forgot a single page he ever read. That played a large role in the shaping of his mind.

Spurgeon’s audience also shaped his ministry. His first pastorate at Waterbeach Chapel was composed mainly of farmers. So he’s forced to communicate in a language that ordinary people could understand. His preaching is simple, clear, beautiful and mesmerizing. Never academic or dry, Spurgeon used his teenage years to hone his words for common people. As he later said, “The Lord Jesus did not say, ‘Feed my giraffes,’ but ‘Feed my sheep.’” That was one of the secrets of his success: he was the people’s preacher. When he goes to London in 1854, he never lost that ability to connect with the hardworking, ordinary people around him.

With the exception of his eschatology (we’re still analyzing this), Spurgeon’s theology never shifts from where it started. From first to last, he is a Christ-centered preacher through and through. One way we measure Spurgeon’s constancy is to compare sermons in which Spurgeon preached from the same passages on different occasions throughout his ministry. This gives us a baseline from which we can trace the development of his thinking. As Spurgeon grows older, his understanding of Scripture deepens and broadens. His physical and emotional sufferings, along with his controversies and life-experience enrich his love of the Bible, but never does he budge one theological inch from his earliest convictions about the core tenants of Christianity.

To really understand Spurgeon, we have to know where he came from, whom he was reading and how his sermon-craft developed. We’re discovering that Spurgeon was not so much a creator; he was a converter. His preaching upcycled older expressions of evangelicalism popular during the Puritan and Great Awakening eras. How fascinating it has been to watch seeds planted in his early Cambridge ministry fully blossom in his later London pastorate.

As an expert in the life and work of Spurgeon, what was the biggest surprise or revelation for you in the sermons?

You know, Spurgeon is often presented as some kind of bulletproof superhero who can do no wrong. After all, the man published more words in the English language than any preacher in history: 150 books, 63 volumes of sermons, a commentary on the Psalms that took two decades to complete, a monthly magazine. He was pastor of the largest Protestant church in the world. He founded sixty-six ministries including a theological college for underprivileged ministers, two orphanages, a book fund, nursing homes, ministries for policemen and prostitutes, among many others. He stood against the tide of his times with courage, conviction and great clarity. He earned multi-millions of dollars from his sermon sales (from 1871-1892 he earned the equivalent of $26 million). Yet Spurgeon died relatively poor because he funneled all of his earnings back into these ministries. He personally shouldered the cost of much of his social work. For these reason, there is so much to appreciate about this great man and so much in his life to cause us to reflect about our own use of time and resources.

But Spurgeon could also bleed. He himself was a deeply-wounded man. He suffered from depression and almost quit the ministry in his early twenties when he watched a balcony collapse and kill seven people in his congregation. These early sermons humanize the man and show us not just his dimples, but his warts as well. For me, that’s been one of the biggest surprises of this project. Here is Spurgeon at his most vulnerable — a young teenage preacher trying to find his voice, trying to figure out how to preach. His mistakes are obvious and he often scratched through words and phrases he wished he didn’t write. Yes, his sermons are bold and zealous. He calls out sin where he sees it in his community. But he also calls out sin he sees within him. In these sermons, we encounter a softer side of Spurgeon. Pride was his “darling” sin, and he wrestled with it fiercely. The prayers he wrote at the end of his sermons reveal a young man utterly desperate for God: “God, help me, a poor thing.” “Oh Father, help through Jesus.” “God, my Father, help me.” “Lord, help thy weakling.” “Lord, revive my stupid soul!” “Oh God bless me or I am undone.” So the project reveals not only new productions from Spurgeon, but also an unseen process.

The other great surprise of this project is the story within the story. When Spurgeon tried to publish these sermons in 1857, Americans throughout the south burned his sermons. Southerners hated Spurgeon because he was an outspoken abolitionist. Spurgeon believed every human life was sacred because we are all made in the image of God — regardless of skin color. Spurgeon called slavery “man-stealing,” and even broke fellowship with pastors who owned slaves.

Southern Baptists were among Spurgeon’s harshest enemies. Spurgeon was ten when Southern Baptists broke from Northern Baptists over slavery in 1845. Before the U.S. Civil War, Spurgeon received death threats. The media defamed his character. And many wanted to see this abolitionist assassinated. How ironic, symmetrical and redemptive that Spurgeon’s early sermons would be published not by his own publisher, Passmore & Alabaster in London, but by Americans. And not only Americans, but Southern Americans. And not only Southern Americans, but Southern Baptist Americans with all the baggage of our bespeckled beginnings.

What’s the relevance of Spurgeon for us today that make these sermons worth printing and reading?

Charles Spurgeon is relevant for today because Jesus Christ is relevant for today. It doesn’t take Spurgeon long to get his readers from the Bible to the cross. He once said, “If a man can preach one sermon without mentioning Christ’s name in it, it ought to be his last.” For this reason, I believe younger generations are primed for Spurgeon perhaps even more than older generations. Has there ever been a preacher in the history more capable of speaking the language of Millennials? Spurgeon doesn’t even need the full 140 characters to get the gospel across! His sermons are pithy and punchy, as tweetable as they are true.

Charles Spurgeon died in 1892, but God still has something for that Victorian teenager to say. Like Abel, I believe Spurgeon “still speaks, even though he is dead” (Hebrews 11:4). He reminds us that the answer to our problems is not politics or presidents. The answer is Jesus Christ. Only when Christ is at the center of our lives can our lives be ultimately centered. In these sermons, future generations will discover one of the greatest amplifiers of God’s glory. Spurgeon once said, “I would fling my shadow through eternal ages if I could.” Truly, his life and legacy have spilled into our own age. And who knows? With the rise of social media, Charles Spurgeon might become more popular in our day than he was even in his very own. As Helmut Thielicke once said of Spurgeon: “This bush from old London still burns and shows no signs of being consumed.”