SALT LAKE CITY — Roger Gannam cites the Bible to define his company’s mission.

That wouldn’t be notable if he worked at a church or food kitchen. But Gannam works at a law firm, suing others and representing those who have been sued.

His employer, Liberty Counsel, advocates for conservative Christian interests in cases related to the sanctity of life, family values and religious liberty.

Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis, right, listens as her attorney Roger Gannam addresses the media on the steps of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky in Covington on July 20, 2015. Davis, who has said she cannot issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples because it would violate her religious beliefs, is being sued by the American Civil Liberties Union on the behalf of two gay couples and two straight couples. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)“We seek to help Christians avail themselves of their First Amendment rights to live out a Christian life the way they want to live it,”said Gannam, assistant vice president of legal affairs for the Orlando, Florida, firm.

Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis, right, listens as her attorney Roger Gannam addresses the media on the steps of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky in Covington on July 20, 2015. Davis, who has said she cannot issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples because it would violate her religious beliefs, is being sued by the American Civil Liberties Union on the behalf of two gay couples and two straight couples. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)“We seek to help Christians avail themselves of their First Amendment rights to live out a Christian life the way they want to live it,”said Gannam, assistant vice president of legal affairs for the Orlando, Florida, firm.

Liberty Counsel is part of the Christian legal movement, a collection of advocacy groups working in the legal, public policy and public relations arenas to advance and protect conservative Christian moral values.

Together, these firms have turned the courts into key battlefields in the culture wars, as will be on display this fall, when Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission is argued before the Supreme Court.

The potentially far-reaching case asks what should win when the conscience rights of small-business owners who object to same-sex marriage clash with civil rights protections for the LGBT community.

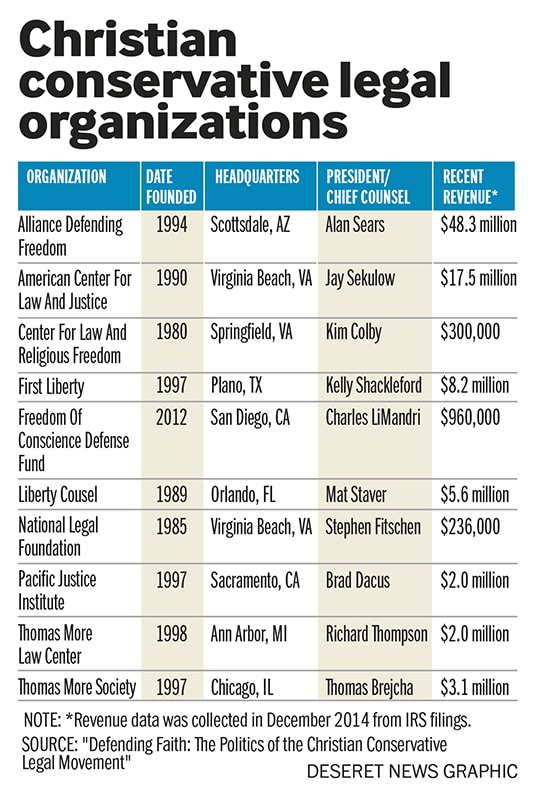

webRNS LEGAL GRAPHIC 080217Alliance Defending Freedom, the most prominent organization in the Christian legal movement, represents Masterpiece Cakeshop, but other Christian firms will be involved in the case as well, offering input on arguments or filing briefs in support of the Christian baker. These groups compete for donations and clients, while recognizing that they’re chasing after the same goals.

webRNS LEGAL GRAPHIC 080217Alliance Defending Freedom, the most prominent organization in the Christian legal movement, represents Masterpiece Cakeshop, but other Christian firms will be involved in the case as well, offering input on arguments or filing briefs in support of the Christian baker. These groups compete for donations and clients, while recognizing that they’re chasing after the same goals.

“There’s plenty of work to go around,” Gannam said. “I think we are co-laborers. We are partners.”

Their shared commitment to splashy media campaigns and aggressive legal tactics have troubled some who work at the intersection of law and religion. Debates over religious freedom are more contentious now than they were in the past, and these organizations may help explain why.

“I think that many of these organizations do overreach, do make implausible claims, and do discredit the cause (of religious freedom) when they do so,” said Douglas Laycock, a religious freedom expert and law professor at the University of Virginia.

Coordinated response

“They’ll coordinate with other organizations,” in terms of how briefs are written, said Daniel Bennett, author of the new book, “Defending Faith: The Politics of the Christian Conservative Legal Movement.”

These groups aren’t reinventing the wheel. They’re borrowing strategies from other legal movements and using court rulings to influence lawmaking, he added.

“Folks that don’t have the representation in the legislative branch to defend their interests” turn to the courts for help, said Bennett, who is an assistant professor of political science at John Brown University, a Christian school in Arkansas.

Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion, helped spark the Christian legal movement, awakening conservative Christian leaders to the idea that they were losing political and cultural clout.

Within 10 years of that ruling, the first Christian legal interest group, the Center for Law and Religious Freedom, was formed.

That first group is one of 10 Christian conservative legal organizations featured in Bennett’s book. These firms protect their religious values through the court system, using cases like the Moral Majority used candidates.

“I define ‘Christian conservative legal organization’ as a multi-issue organization dedicated to the interests of Christian conservatives primarily through legal advocacy, including litigation and public education,” Bennett said.

His definition excludes Becket Law, the high-profile firm behind many religious freedom cases, because it’s focused solely on religious liberty issues. Other interest groups, such as Concerned Women for America, are also left off the list, because legal advocacy is not their primary mission.

Attorney Douglas Laycock, center, characterizes his argument before the Supreme Court on behalf of an Arkansas prison inmate who says his Muslim beliefs that require him to grow a beard are being violated by prison rules that prevent beards on Oct. 7, 2014, in front of the court in Washington. Laycock, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, is working with the Beckett Fund for Religious Liberty which prevailed in the Hobby Lobby case last June. At left is Hannah Smith, a senior counsel with the Becket Fund. At right is Emily Hardman and Diana Verm, far right, both of the Beckett Fund. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)The growth and success of Christian conservative legal organizations has earned them some enemies, especially at a time when religious freedom protections increasingly clash with LGBT rights.

Attorney Douglas Laycock, center, characterizes his argument before the Supreme Court on behalf of an Arkansas prison inmate who says his Muslim beliefs that require him to grow a beard are being violated by prison rules that prevent beards on Oct. 7, 2014, in front of the court in Washington. Laycock, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, is working with the Beckett Fund for Religious Liberty which prevailed in the Hobby Lobby case last June. At left is Hannah Smith, a senior counsel with the Becket Fund. At right is Emily Hardman and Diana Verm, far right, both of the Beckett Fund. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)The growth and success of Christian conservative legal organizations has earned them some enemies, especially at a time when religious freedom protections increasingly clash with LGBT rights.

Three Christian conservative law firms — Alliance Defending Freedom, Pacific Justice Institute and Liberty Counsel — appear on the Southern Poverty Law Center’s list of hate groups because of their “anti-LGBT” positions.

“There used to be broad, bipartisan support for religious liberty. That has sort of melted away now,” said Hiram Sasser, deputy chief counsel for First Liberty Institute.

Alliance Defending Freedom did not respond to multiple interview requests.

By pairing religious freedom law with their moral agenda, Christian conservative legal organizations have hurt religious liberty’s reputation, Laycock said.

“A claim that abortion or same-sex marriage should be illegal for everybody is not a religious liberty claim. It is a claim that conservative Christian morality should be imposed by law on everyone else,” he said.

However, linking cases with moral concerns is a powerful political and fundraising strategy. When selecting cases, the firms consider whether an issue will play well in the press and catch the attention of potential donors, Bennett said.

“They’re looking for cases that set a precedent and earn them a little money in terms of fundraising,” he said. The groups profiled in “Defending Faith” bring in anywhere from $300,000 to $48.3 million in annual revenue, according to Bennett’s research.

Gannam resists the notion that faith-based legal activism harms non-Christian Americans.

“We are distinctively Christian, but the religious liberties we secure and vindicate are for everyone, not just for Christians,” Gannam said.

Beyond the courtroom

The drawback of tapping into the power of the courts is that most lawsuits are all-or-nothing propositions, Bennett said.

“The courts can be good when you’re winning, but really, really bad when you’re losing,” he said.

Christian conservative legal organizations mitigate the risks of losing by proposing legislation, organizing educational conferences and training supporters to effectively interact with the media.

“They’re trying to coordinate grass-roots mobilization, media advocacy and litigation,” said Amanda Hollis-Brusky, co-author of a forthcoming book on law schools that feed the Christian legal movement.

Gannam actually began his religious freedom-related litigation work by attending a training program hosted by the Alliance Defending Freedom. At the time, he was a commercial litigator focused on business transactions, but exposure to the Christian legal movement changed his course.

“I had to work at the traditional practice of law and make money so I could support my religious liberty habit,” he said.

He joined the Liberty Counsel staff three years ago, diving into full-time religion-related advocacy.

The organization looks for opportunities to influence the direction of the law, through relationships with lawmakers.

“We have a dedicated lawyer in D.C. who heads up our public policy arm. He spends all of his time meeting with legislators and other policy organizations trying to think through and articulate appropriate policy goals and sometimes offering model legislation,” Gannam said.

Through similar initiatives at the state level, Christian conservative legal organizations have emerged as key opponents of so-called “fairness for all” bills, which seek to balance religious liberty with LGBT non-discrimination protections.

Robin Fretwell Wilson, director of the family law and policy program at the University of Illinois College of Law, has helped draft these compromise bills in multiple states, often running into members of the Christian legal movement in the process.

“I think it is fair to say they are moving heaven and earth in the states to make protecting gay rights look like it always comes at the expense of religious persons and communities,” she said.

Liberty Counsel leaders believe the “fairness for all” concept offers a weak return for people of faith compared to what’s given to members of the LGBT community, Gannam said.

Although court cases continue to represent the core of these organizations’ work, political activism and community outreach may become more valuable in the future, as religion-related debates expand and evolve, Sasser said.

Taking the long view

At first, the Supreme Court’s ruling legalizing same-sex marriage seemed like a lethal blow to Christian conservative legal organizations. They’d spent years opposing gay marriage, but it still became the law of the land.

In reality, the outcome ushered in new varieties of religious freedom cases, allowing these firms to reshape their public image, focusing on their support of personal liberties rather than their opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion.

Rebranding comes with its own set of challenges. Religious freedom protections are increasingly portrayed as a “license to discriminate.”

Younger Americans, in particular, seem to be wary of conscience rights. In a recent Public Religion Research Institute survey, 1 in 4 Americans ages 18 to 29 favored allowing small-business owners to refuse to provide products or services to the LGBT community for religious reasons, compared to one-third of Americans ages 30 to 64 and 43 percent of Americans older than 65.

First Liberty has responded to the contentious religious liberty climate by working to diversify its clientele, Sasser said, noting that judges and Americans in general are more responsive to the needs of minority faith groups.

“I worry that there are judges who would be sympathetic to protecting a Hindu temple or synagogue or mosque, but maybe wouldn’t worry about a zoning case against a church,” he said.

The key is for Liberty Counsel and other Christian conservative legal organizations to stay committed to making a difference in the long-term, Gannam said.

“As a Christian organization, we draw comfort and encouragement from the Scripture: Do not grow weary of doing good,” he said. “Our mission doesn’t allow us to get tired of trying, even if there are short-term setbacks.”

Kelsey Dallas writes for The Deseret News.