(The Conversation) —The earliest Latin commentary on the Gospels, lost for more than 1,500 years, has been rediscovered and made available in English for the first time. The extraordinary find, a work written by a bishop in northern Italy, Fortunatianus of Aquileia, dates back to the middle of the fourth century.

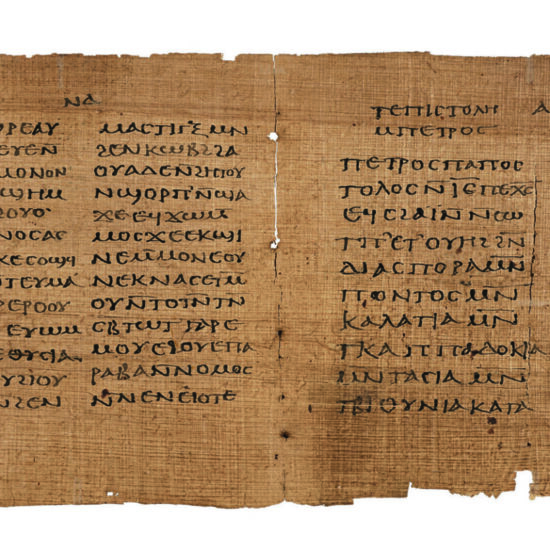

The biblical text of the manuscript is of particular significance, as it predates the standard Latin version known as the Vulgate and provides new evidence about the earliest form of the Gospels in Latin.

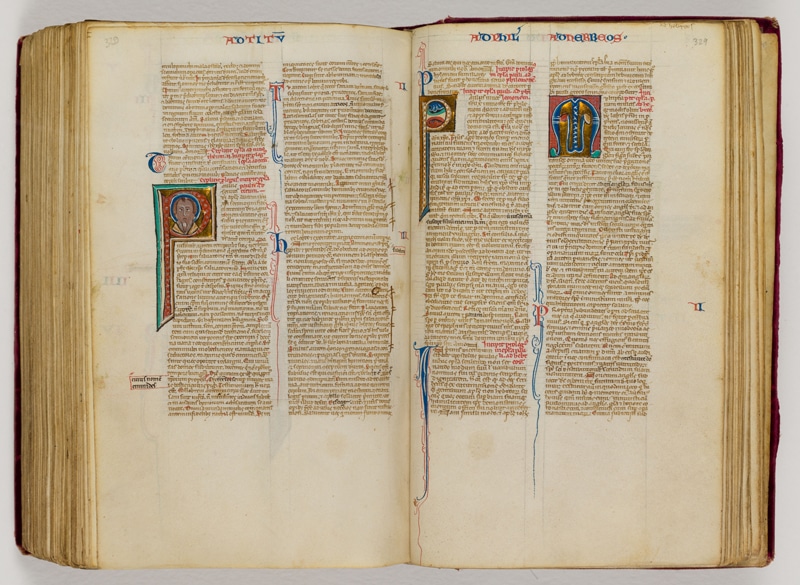

Fortunatianus manuscript: now available online; by permission of Cologne Cathedral Library. Author providedDespite references to this commentary in other ancient works, no copy was known to survive until Lukas Dorfbauer, a researcher from the University of Salzburg, identified Fortunatianus’ text in an anonymous manuscript copied around the year 800 and held in Cologne Cathedral Library. The manuscripts of Cologne Cathedral Library were made available online in 2002.

Fortunatianus manuscript: now available online; by permission of Cologne Cathedral Library. Author providedDespite references to this commentary in other ancient works, no copy was known to survive until Lukas Dorfbauer, a researcher from the University of Salzburg, identified Fortunatianus’ text in an anonymous manuscript copied around the year 800 and held in Cologne Cathedral Library. The manuscripts of Cologne Cathedral Library were made available online in 2002.

Scholars had previously been interested in this ninth-century manuscript as the sole witness to a short letter which claimed to be from the Jewish high priest Annas to the Roman philosopher Seneca. They had dismissed the 100-page anonymous Gospel commentary as one of numerous similar works composed in the court of Charlemagne. But when he visited the library in 2012, Dorfbauer, a specialist in such writings, could see that the commentary was much older than the manuscript itself.

In fact, it was none other than the earliest Latin commentary on the Gospels.

Pearls of wisdom

In his De Viris Illustribus (Lives of Famous Men), written at the end of the fourth century, Saint Jerome, who was also responsible for the revision of the Gospels and the translation of the Hebrew Scriptures known as the Vulgate, included an entry for Fortunatianus – who had been bishop of the northern Italian diocese of Aquileia some 50 years earlier. This prominent cleric had written a Gospel commentary including a series of chapter titles, which Jerome described as “a pearl without price” and had consulted when writing his own commentary on the Gospel of Matthew.

Later Christian authors, such as Rabanus Maurus and Claudius of Turin, searched for it in vain. As with so many works from antiquity, it seemed to have been lost, the remaining copies destroyed in a Vandal raid or eaten by mice in a dusty library.

Among the features which attracted Dorfbauer’s attention was a long list of 160 chapter titles detailing the contents of the commentary, which corresponded to Jerome’s description of Fortunatianus’ work. In addition, the biblical text of the Cologne manuscript did not match the standard version of the Gospels produced by Jerome, but seemed to come from an earlier stage in the history of the Latin bible.

Groundbreaking discovery

This was where the University of Birmingham came in. The university’s Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing is home to long-term projects working on new editions of the Bible in Greek and Latin. As a specialist in the Latin New Testament, I was able to compare the biblical quotations in the Cologne manuscript with our extensive databases. Parallels with texts circulating in northern Italy in the middle of the 4th century offered a perfect fit with the context of Fortunatianus.

Astonishingly, despite being copied four centuries after the last reference to his Gospel commentary, this manuscript seemed to preserve the original form of Fortunatianus’ groundbreaking work.

Such a discovery is of considerable significance to our understanding of the development of Latin biblical interpretation, which went on to play such an important part in the development of Western thought and literature. In this substantial commentary, Fortunatianus is reliant on even earlier writings which formed the link between Greek and Latin Christianity.

This sheds new light on the way the Gospels were read and understood in the early Church, in particular the reading of the text known as “allegorical exegesis” in which elements in the stories are interpreted as symbols. So, for example, when Jesus climbs into a boat on the Sea of Galilee, Fortunatianus explains that the sea which is sometimes rough and dangerous stands for the world, while the boat corresponds to the Church in which Jesus is present and carries people to safety.

There are also moments of insight into the lives of fourth-century Italian Christians, as when the bishop uses a walnut as an image of the four Gospels or holds up a Roman coin as a symbol of the Trinity.

English translation

In the form of a single (no longer anonymous) manuscript, or even a scholarly edition of the Latin text, it will still be some time before this work becomes as widely known as the famous writings of later Christian teachers such as Ambrose, Augustine and Jerome.

For that reason, I have worked closely with Dr Dorfbauer to prepare an English translation of his full Latin edition of the commentary, the first ever to be produced.

This will enable a much wider audience to take account of this rediscovered work. In fact, this English version may be the form in which most people will encounter Fortunatianus’ commentary – as studying languages is now a much smaller component in theological study and online translation tools are beginning to produce more satisfactory results.

![]() But for the fullest appreciation of this work, it will still be necessary to put alternatives to one side and consult the original – which is how the commentary was rediscovered in the first place.

But for the fullest appreciation of this work, it will still be necessary to put alternatives to one side and consult the original – which is how the commentary was rediscovered in the first place.

Hugh Houghton, is deputy director at the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing, University of Birmingham. Houghton’s translation is published under contract by De Gruyter publishers, although he receives no royalties for sales of this book. The translation was completed as part of the European Research Council COMPAUL project, which also funded its publication in open access. Houghton has also received research funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the British Academy. This article was originally published on The Conversation.