A popular myth surrounds the hymn “Amazing Grace.” The story goes something like this: John Newton was a wretched slave trader, but then got saved, quit the slave business, became an abolitionist and wrote the beloved hymn. It’s like rewriting the story of Paul on the way to Damascus as a musical on the high seas. A beautiful, inspiring story.

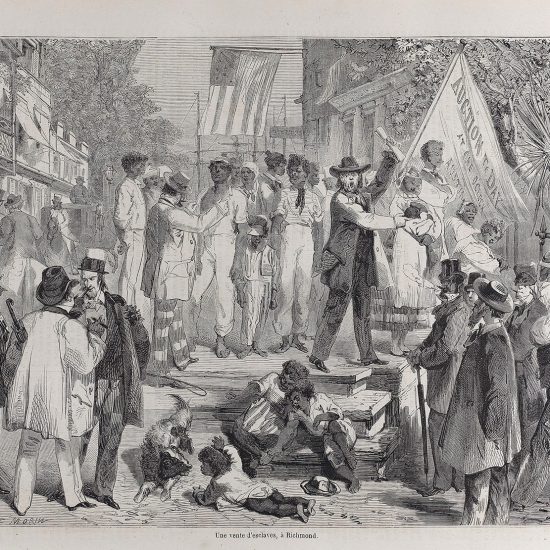

Brian KaylorToo bad that’s not quite the real story, as Adam Hochschild notes in “Bury the Chains.” Newton did work on slave boats, showing no grace as he bought, tortured and sold human beings as if they were lowlier than cattle. He did become a Christian after surviving a violent storm in 1748 at the age of 23. But once upon land, he signed up for another slave boat job. And then another, eventually becoming captain of a slave boat after his conversion. Newton finally stopped sailing on slave boats in 1754, but only because he suffered a stroke. Even then, he kept investing in slave-trading companies for years.

Brian KaylorToo bad that’s not quite the real story, as Adam Hochschild notes in “Bury the Chains.” Newton did work on slave boats, showing no grace as he bought, tortured and sold human beings as if they were lowlier than cattle. He did become a Christian after surviving a violent storm in 1748 at the age of 23. But once upon land, he signed up for another slave boat job. And then another, eventually becoming captain of a slave boat after his conversion. Newton finally stopped sailing on slave boats in 1754, but only because he suffered a stroke. Even then, he kept investing in slave-trading companies for years.

He eventually studied for the Anglican priesthood and starting writing hymns. He wrote “Amazing Grace” in 1772, but did not start to reconsider the morality of slavery until 1780 — 32 years after his conversion. Eight years later, he finally wrote publicly against the slave trade.

I’m not suggesting we rip “Amazing Grace” from our hymnals or stop singing it. But we should stop sharing the sanitized story of Newton’s life. How we tell a story matters because the details teach us the moral of the story. The simple version makes it seem like someone just needs to get saved and then magically they will walk away from all bad things like slave trading. That story fits well with our hit-and-run evangelism efforts that focus on how many people say a prayer over making disciples.

The real story of Newton’s life teaches us important lessons we miss by telling the other tale. First, conversion isn’t the end result, but the first step in becoming a new creation. It shouldn’t have taken so long on something as significant as slavery, but fortunately Newton’s faith grew for decades until he finally could see after a lifetime of moral blindness.

A second lesson from Newton’s story is the need for us to move beyond a shallow faith that sings about getting some amazing grace in the afterlife while ignoring the plight of our neighbors here and now. Newton may have found personal grace at a young age, but it took him decades longer to start to understand the biblical imperative of justice or even basic biblical teachings about love of neighbor. The faith of slave traders doesn’t sound so sweet.

For too long, our churches have been filled with young Newtons, essentially still trading slaves even after converting. Slavery in the U.S. continued sixty years after the British abolition because of “good” church-going people. Thousands of blacks were lynched by “good” churchgoing people. Blacks were forced to use separate water fountains, bathrooms and schools because of the fears held by “good” church-going people. Monuments to celebrate white supremacists were erected by “good” church-going people. Racist leaders were elected, praised and defended by “good” church-going people.

We need to convert again, this time away from cultural Christendom preaching power, fear and hate. Events in Charlottesville, Va., prove we cannot wait decades for this moral conversion. It’s not enough to say we no longer own slaves or crucify blacks with a rope and a tree. We must continue to detox our lives and theology until we remove any vestiges of the slaveholder faith passed down to us.

Clarence Jordan, a white Baptist civil rights leader, lamented churches didn’t lead the way in pushing integration and start the movement at the communion table instead of at bus depots or Woolworth counters. He noted “the Supreme Court is making more pagans be Christian than the Bible is making Christians be Christian.” Jordan added, “If anybody has to bear the blame and guilt for all the sit-ins and all the demonstrations and all the disorder in the South, it is the whitewashed Christians who have had the word of God and have locked it up in their hearts and refused to do battle with it.”

Brian Kaylor is editor and president of Word&Way.

See also: