JACKSON, Miss. (RNS) — In a few weeks (July 1), Les Ferguson Jr. will move on from the pulpit at Lake Harbour Church of Christ in Ridgeland, Miss., just north of Jackson, to a new position in Oxford, home to “Ole Miss,” the University of Mississippi.

The move and the university community, he said, offer the potential for more personal and spiritual growth. It’s also another move toward wholeness for a man whose life was fractured by tragedy nearly seven years ago.

Les and Karen Ferguson, with Conner, Casey and Cole. Not pictured is the couple’s oldest son, Kyle. Karen and Cole were murdered on Oct. 10, 2011. Photo courtesy of Les Ferguson Jr.On the afternoon of Oct. 10, 2011 — Ferguson’s 24th wedding anniversary — his wife, Karen, and the couple’s son Cole, 21, were shot to death in the family’s home in Gulfport, Miss., near the church where Ferguson was then preaching.

Les and Karen Ferguson, with Conner, Casey and Cole. Not pictured is the couple’s oldest son, Kyle. Karen and Cole were murdered on Oct. 10, 2011. Photo courtesy of Les Ferguson Jr.On the afternoon of Oct. 10, 2011 — Ferguson’s 24th wedding anniversary — his wife, Karen, and the couple’s son Cole, 21, were shot to death in the family’s home in Gulfport, Miss., near the church where Ferguson was then preaching.

The apparent killer, Paul Ellis Buckman, 70, had attended the church until being charged three months earlier with sexually assaulting Cole, who had cerebral palsy. The same day that Karen and Cole were killed, Buckman was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his apartment two miles away.

“There were mighty dark days,” Ferguson remembered.

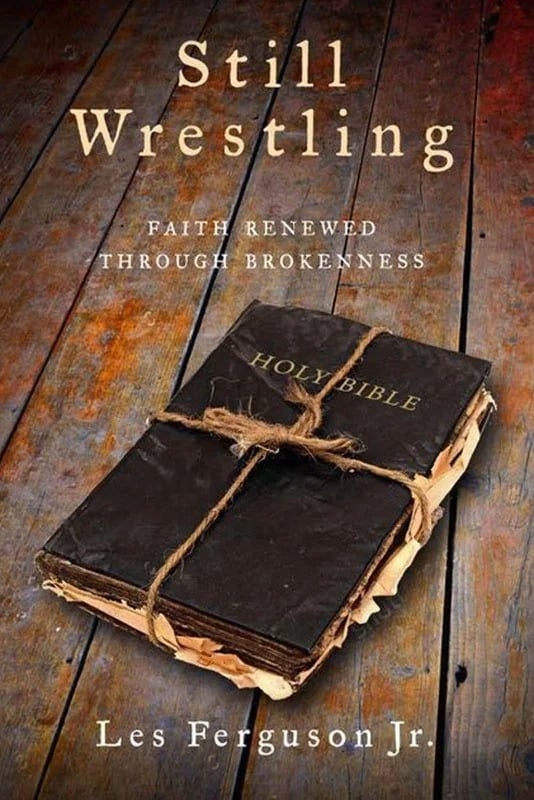

Now, he is the author of the new book “Still Wrestling: Faith Renewed Through Brokenness,” which explores the doubt that consumed him after the double murder.

Ferguson couldn’t imagine ever trusting in God again, much less proclaiming the gospel from a pulpit.

“Still Wrestling: Faith Renewed Through Brokenness” by Les Ferguson Jr. explores questions of faith and doubt that consumed the Mississippi minister after his wife and disabled son were slain in 2011. Image courtesy of Leafwood PublishersHe was brought back in part by the people who reached out to him to return to his calling. “You took a broken, timid, uncertain man and gave him a chance to do ministry again,” he tells the Lake Harbour congregation in the opening acknowledgments to “Still Wrestling.”

“Still Wrestling: Faith Renewed Through Brokenness” by Les Ferguson Jr. explores questions of faith and doubt that consumed the Mississippi minister after his wife and disabled son were slain in 2011. Image courtesy of Leafwood PublishersHe was brought back in part by the people who reached out to him to return to his calling. “You took a broken, timid, uncertain man and gave him a chance to do ministry again,” he tells the Lake Harbour congregation in the opening acknowledgments to “Still Wrestling.”

A mother’s sacrifice

It was a long time before Ferguson could find his voice at all. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, 700 mourners filled the church in Gulfport, Orange Grove Church of Christ, for a memorial service. Karen Ferguson was remembered as a hero who helped the couple’s youngest son, Casey, then 5, escape the killer.

The 4-foot-11, 100-pound mother then turned to defending Cole. Another son, Conner, then 14, had gone to play miniature golf with friends that afternoon. Kyle, the eldest, lived in Kentucky, where he served as a campus minister. Les Ferguson was at a preachers’ meeting in nearby Biloxi.

In giving the eulogy for both victims, Les Ferguson’s younger brother, Billy, also a minister, described Cole as a hero, too, recalling his “larger than life” smile.

“His love for family and friends and church was vibrant and unencumbered by his physical disability,” Billy Ferguson said.

For his part, Les Ferguson said all the right things — at first.

“God didn’t do this,” he told a reporter in the days after the shooting. “This was just evil.”

But as weeks and months passed, he avoided church, spending his time alone. As he scrubbed his wife’s and child’s bloodstains from the walls, the minister’s despair overwhelmed him. He pushed everyone out of his life, except for his remaining immediate family and a few close friends.

“I didn’t want someone to pat me on the back and tell me it was going to be OK,” he said. “I didn’t want somebody to quote a Bible verse to me. I just wanted to be left alone.”

A change of scene

Ferguson knew he had to leave the Gulf Coast community to which he’d ministered for 13 years the day he moved a love seat in his living room and found bullet holes in the floor.

He moved 200 miles away to Vicksburg, on the Mississippi River.

He began to write as a way to heal, launching an online journal called Desperately Wanting to Believe Again that would become the basis for his 224-page book, published by Texas-based Leafwood, a branch of Abilene Christian University Press.

“I never quit believing,” Ferguson said. “The name probably should have been Desperately Wanting to Trust Again because it was more about my journey of learning to trust God again. I used the blog to rant and rave and whine and fuss and praise as it came to me.”

While in Vicksburg, Ferguson reconnected with a former sweetheart, Becki Berryman. The mother of two teenage boys, she had remained a close friend of Ferguson’s sister after she and Ferguson had dated as teenagers. They married in 2012.

Some of the blended Ferguson family during a beach trip to Destin, Fla. Pictured from left are Casey Ferguson, 12; Becki Ferguson; Max Rangel, 17; Les Ferguson Jr.; Michael Rangel, 20; and Conner Ferguson, 21. Photo courtesy of Les Ferguson Jr.“It absolutely astounds me when I think of all the changes we have been through,” he told RNS. “My youngest son is less than a year away from being a teenager. My oldest son is the father to a 2-year-old. We’ve experienced high school graduations and graduate degrees. We’ve gone through career changes and come full circle back to ministry again.”

Some of the blended Ferguson family during a beach trip to Destin, Fla. Pictured from left are Casey Ferguson, 12; Becki Ferguson; Max Rangel, 17; Les Ferguson Jr.; Michael Rangel, 20; and Conner Ferguson, 21. Photo courtesy of Les Ferguson Jr.“It absolutely astounds me when I think of all the changes we have been through,” he told RNS. “My youngest son is less than a year away from being a teenager. My oldest son is the father to a 2-year-old. We’ve experienced high school graduations and graduate degrees. We’ve gone through career changes and come full circle back to ministry again.”

Casey, who witnessed the attack and is now 12, has done remarkably well, Ferguson said.

“Early on, we were told repeatedly that the young are very resilient,” the father added. “And that has been our experience.”

Finding his voice again

After the double murder, Ferguson thought he’d never preach again.

But when Lake Harbour sought a minister in the spring of 2014, the church’s six elders saw Ferguson as someone whose experience would give him insight and empathy no matter what their members had gone through.

“We felt like Lake Harbour could be a big help to him, too, personally and in his faith,” elder Greg Palmer said of Ferguson’s hiring.

Minister Les Ferguson Jr. and his wife, Becki, left, greet church members after a Sunday morning assembly at the Lake Harbour Church of Christ in Ridgeland, Miss., north of the state capital of Jackson, in 2014. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr“It’s not one of those things where he tells you the terrible story every Sunday,” elder Morris Houston said when Ferguson was hired in 2014. “But in his sermons, you get pieces of what he has recovered from … and I think it has a big impact.”

Minister Les Ferguson Jr. and his wife, Becki, left, greet church members after a Sunday morning assembly at the Lake Harbour Church of Christ in Ridgeland, Miss., north of the state capital of Jackson, in 2014. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr“It’s not one of those things where he tells you the terrible story every Sunday,” elder Morris Houston said when Ferguson was hired in 2014. “But in his sermons, you get pieces of what he has recovered from … and I think it has a big impact.”

Their hunch has paid off.

“God has seen fit to take all of my brokenness and help me be a more compassionate, grace-filled minister,” Ferguson told RNS. “And, as much as I wish we hadn’t experienced some of our pain and heartbreak … never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined the blessed life our family now lives.”

John Dobbs, minister for the Forsythe Church of Christ in Monroe, La., said he’s grateful to see his close friend remarried and preaching again.

Dobbs suffered a tragedy of his own in 2008 when his 18-year-old son, John Robert Dobbs, was struck and killed on an interstate. Ferguson spoke at John Robert’s funeral.

“In his tenderest moments, Les remains crushed by his losses,” Dobbs said. “Grief runs like a river beneath his daily life. But in his tough moments, Les has learned to speak truthfully and forcefully for the abused and threatened.

“With God’s help, Les has taken the weapons Satan meant to destroy and turned them into tools in the hands of the Savior,” his friend added. “There’s a beauty to this beastly story that will only be realized in the resurrection morning.”

Ferguson said he wrote “Still Wrestling,” which took him three years to finish, as a way “not only of dealing with all of my own hurt and pain and loss and difficulty, but also wanting to help others who struggle, too.”

What does he hope readers take away from the book?

“That no matter how broken they are, no matter how damaged they might be, no matter how difficult life is, God is still there,” he said, “and they just need to keep wrestling with him.”

Nearly seven years after the shooting, the minister said he’s definitely in a better place.

But what he’s learned, he added, is that he’ll always be wrestling.

“That’s what God is looking for — for us to wrestle with him and to continue to grow,” Ferguson said. “That’s a part of the struggle.”