(RNS) — Opponents of the Miss America pageant’s decision to discontinue the swimsuit portion of their competition have blamed liberals, feminists, and the #MeToo movement, and with good reason. None, however, have blamed Christians.

Why not?

Miss Louisiana Laryssa Bonacquisti, center, reacts after advancing to the evening gown round of the Miss America 2018 pageant on Sept. 10, 2017, in Atlantic City, N.J. (AP Photo/ Noah K. Murray)Christians, so often known for trumpeting values like modesty, inner beauty, and the dignity of women have a natural place on the front lines of the battle against the bikini. Why weren’t Christians waging their own culture war against the Miss America pageant, as some have against abortion and gay marriage?

Miss Louisiana Laryssa Bonacquisti, center, reacts after advancing to the evening gown round of the Miss America 2018 pageant on Sept. 10, 2017, in Atlantic City, N.J. (AP Photo/ Noah K. Murray)Christians, so often known for trumpeting values like modesty, inner beauty, and the dignity of women have a natural place on the front lines of the battle against the bikini. Why weren’t Christians waging their own culture war against the Miss America pageant, as some have against abortion and gay marriage?

As it turns out, they used to.

Long before feminists began protesting the Miss America pageant in the late 1960s, Christian groups had signaled their disapproval. When the Miss America pageant began in 1921, Baptists, Quakers and Methodists alike called for Christians to steer clear of Atlantic City, N.J., and other bathing revues.

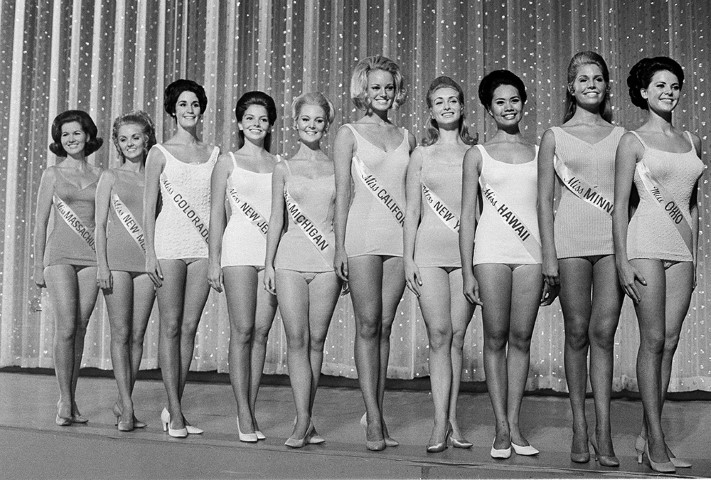

Ten semi-finalists of the Miss America pageant pose in their swimsuits in Atlantic City, N.J., Sept. 6, 1969. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz)Southern Baptists passed a “Resolution on Beauty Contests” in 1926 that stated, in part, that “‘Whereas, ‘Beauty contests’ and so-called ‘bathing revues’… tend to lower true and genuine respect for womanhood … We, the Southern Baptist Convention do deplore and condemn all such contests and revues.”

Ten semi-finalists of the Miss America pageant pose in their swimsuits in Atlantic City, N.J., Sept. 6, 1969. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz)Southern Baptists passed a “Resolution on Beauty Contests” in 1926 that stated, in part, that “‘Whereas, ‘Beauty contests’ and so-called ‘bathing revues’… tend to lower true and genuine respect for womanhood … We, the Southern Baptist Convention do deplore and condemn all such contests and revues.”

The next year, a religious leader declared in The New York Times that the pageant was “damaging to the morals of men, women and children.” In a resolution to Atlantic City’s commission and pageant directors, the Atlantic County Federation of Church Women wrote, “We are persuaded that the moral effect on the young women entrants and the reaction generally is not a wholesome one.”

These arguments sound similar to those made later in the century by feminists who also believed Miss America was “an image that oppresses women in every area in which it reports to represent us.”

In contrast to the 1968 feminist protest of the pageant, however, whose efforts had no tangible effect, the earlier Christian critiques helped shut the pageant down for five years.

Fast forward to 2007 when Deidre Downs, Miss America 2005 and then a Baptist, appeared on the cover of Missions Mosaic: The Magazine for Women on Mission, a publication of the Woman’s Missionary Union of the Southern Baptist Convention.

What led the Christians give up the fight and join the pageant?

Hosts Chris Harrison, from left, and Lara Spencer with winner Miss New York Kira Kazantsev during the Miss America 2015 pageant on Sept. 14, 2014. Photo by Ida Mae Astute, courtesy of ABCAs it turns out, in a stroke of genius, pageant organizers won Christians over to their side by hiring one of their own to help reboot and remake the pageant.

Hosts Chris Harrison, from left, and Lara Spencer with winner Miss New York Kira Kazantsev during the Miss America 2015 pageant on Sept. 14, 2014. Photo by Ida Mae Astute, courtesy of ABCAs it turns out, in a stroke of genius, pageant organizers won Christians over to their side by hiring one of their own to help reboot and remake the pageant.

In 1935, Atlantic City businessmen hired Lenora Slaughter, a Southern Baptist from Florida, to revive the pageant. In an effort to sanitize the salacious revue, Slaughter shunned the word “bathing suit” in favor of the term “swimsuit,” playing up contestants’ athleticism rather than sensuality. She added a talent component and instituted scholarships for winners. A new rule banned contestants from visiting bars and nightclubs, established curfews, and forbade contestants to speak to any man alone.

Christians felt increasingly at home in the pageant as Slaughter reformed it, inviting some of them to serve as hostesses, judges, or board members. In time, many who once opposed the pageant most vocally became its fiercest allies.

To be sure, some Christians continued to oppose the spectacle, but gradually their voices were marginalized. The pageant came to be seen as a preserver and protector of American womanhood, even an antidote to feminism. The Miss America pageant promoted an ideal of femininity in keeping with Christian values, one that did not threaten to usurp male power.

The relationship between Christianity and the pageant was formalized when Miss America 1965, Vonda Kay Van Dyke, became the first Miss America to speak openly about her faith.

Vonda Kay Van Dyke. Photo courtesy of Creative CommonsAt the time, Miss America contestants signed a contract agreeing not to talk about religion or politics, but when emcee Bert Parks asked Van Dyke whether her Bible served as her good luck charm, Van Dyke seized the opportunity: “I do not consider my Bible a good-luck charm. It is the most important book I own,” she answered.

Vonda Kay Van Dyke. Photo courtesy of Creative CommonsAt the time, Miss America contestants signed a contract agreeing not to talk about religion or politics, but when emcee Bert Parks asked Van Dyke whether her Bible served as her good luck charm, Van Dyke seized the opportunity: “I do not consider my Bible a good-luck charm. It is the most important book I own,” she answered.

After receiving positive responses from the public, pageant officials decided to change the rules to allow for open religious expression.

Not all women who participated in beauty contests claimed to be Christian. (Perhaps despite the wishes of the organizers: Bess Myerson, Miss America 1945 and the only Jewish winner in pageant history, was asked to change her name to sound less Jewish.)

Still, more than half of the winners after Van Dyke’s coup have professed Christianity. Miss America 1980, Cheryl Prewitt (Pentecostal), Miss America 1995, Heather Whitestone (Baptist), and Miss America 2007, Lauren Nelson (Methodist), explicitly saw pageants as part of their religious journeys. And all of them donned a swimsuit as part of the credentialing process.

Some Christian contestants claimed that competing in swimsuits offered them a way to demonstrate that they had taken seriously the Bible’s command to treat their bodies as temples of the Holy Spirit. Others asserted that choosing a one-piece swimsuit provided them a platform from which to advocate for modesty. Most saw no need to say anything at all.

But even those Christian competitors who felt compelled to explain their participation believed that the swimsuit portion built character more than it threatened it. They absorbed the language of health and fitness used by the pageant and made it their own. The swimsuit competition was not an exercise in objectification, but an opportunity to showcase the bodies that God had given them (and for which they had worked so tirelessly).

Shelli Renee Yoder, Miss Indiana 1992 and an eventual opponent of pageants wrote, “The possibility of achieving perfection arrested me and seemed to clarify the Gospel of Matthew’s prescription, ‘Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.’”

Yoder’s pursuit of perfection landed her a preliminary swimsuit award and second runner-up to Miss America.

The Miss America pageant, the swimsuit portion included, provided Christian young women an opportunity to test their faith, grow in their faith, and live out their faith.

Why weren’t Christians the ones to ruin the Miss America pageant? Because their sisters, daughters, and granddaughters were participating as their churches bought program ads, hosted watch parties, and invited winners to speak.

It took a cultural moment like #metoo to call a largely Christian enterprise to repentance.

Mandy E. McMichael is an assistant professor of religion and associate director of ministry guidance at Baylor University. Her forthcoming book, “Miss America’s God: Faith and Identity in America’s Oldest Pageant,” will be published by Baylor University Press.