NASHVILLE (BP) — Most Americans likely know of Francis Scott Key’s passion for the United States, expressed in his writing of the national anthem. Far fewer know he also was a passionate advocate of Sunday School whose leadership in the Sunday School movement helped evangelize the West.

Most Americans likely know of Francis Scott Key’s passion for the United States, expressed in his writing of the national anthem. Far fewer know he also was a passionate advocate of Sunday School whose leadership in the Sunday School movement helped evangelize the West.As the United States celebrates its 242nd birthday, Christian educators say Key’s two passions went hand in hand. Sunday School could once again, they say, be a catalyst for spiritual and moral renewal in America.

Most Americans likely know of Francis Scott Key’s passion for the United States, expressed in his writing of the national anthem. Far fewer know he also was a passionate advocate of Sunday School whose leadership in the Sunday School movement helped evangelize the West.As the United States celebrates its 242nd birthday, Christian educators say Key’s two passions went hand in hand. Sunday School could once again, they say, be a catalyst for spiritual and moral renewal in America.

“America and Sunday School literally grew up together,” said David Francis, a retired director of Sunday School for LifeWay Christian Resources who has referenced Key in his writings. “Nowhere else in the world has Sunday School been embraced like in America. Nowhere else in the world has the idea of a constitutional republic been sustained like in America. Two ideas. Both of God. At the same time. Spreading together across a continent. What a fortunate coincidence.”

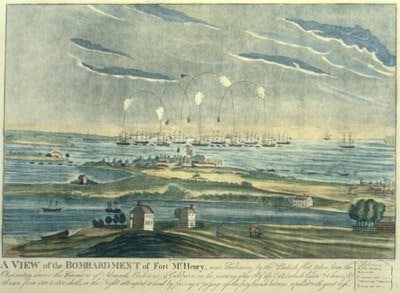

Born in 1779, Key was a Maryland attorney, author and poet. In 1814, he wrote the poem “Defense of Fort M’Henry” after watching the all-night bombardment of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry from a British ship during the War of 1812. Key had gone aboard the ship as an American envoy to negotiate a prisoner release and was not allowed to disembark until after the attack.

In the morning, the sight of an American flag still waving over the fort inspired Key’s poem, which he soon had set to music. Under the title “The Star-Spangled Banner,” it became the national anthem more than a century later.

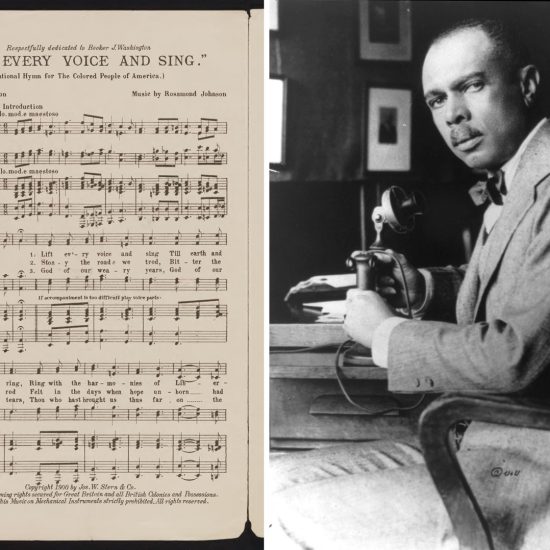

Lesser known is that Key was “an earnest Christian,” “a teacher of a large Bible class” and an Episcopalian, according to Edwin Wilbur Rice’s 1917 book “The Sunday School Movement and the American Sunday-School Union” (ASSU). Key joined the ASSU board of managers in 1824, the year the union changed its name from the Sunday and Adult School Union.

The ASSU’s 1835 Annual listed Key as a “lifetime member” based on his contribution of at least $30 — the equivalent of $815 today. The 1840 and 1841 Annuals listed him among the union’s vice presidents.

Francis wrote in his book “Missionary Sunday School” that the ASSU’s aim was to start Sunday Schools across America where individuals from lower economic classes heard the Gospel and learned to read and write “using the Bible as a primary text.” Sunday Schools typically comprised children “who rarely or never attend[ed] church,” and adult classes often formed as a secondary ministry.

Key chaired an 1830 ASSU meeting in Washington which instituted the “Mississippi Valley Enterprise,” a campaign that established west of the Appalachian Mountains more than 61,000 Sunday Schools for some 2.7 million pupils over the next 50 years, Francis wrote. Many of those Sunday Schools developed into churches, some Baptist, in areas previously without an evangelical witness while others became weekday schools before the era of American public education.

When Key died in 1843, the ASSU stated in its Annual, “By the decease of the Hon. Francis S. Key, of the District of Columbia, we lose one of our earliest and most steadfast advocates and patrons. His frequent and liberal contributions to our funds, and his readiness at all times to vindicate the principles and advance the usefulness of the Society, furnished unequivocal evidence of his interest in our cause.”

When Key died in 1843, the ASSU stated in its Annual, “By the decease of the Hon. Francis S. Key, of the District of Columbia, we lose one of our earliest and most steadfast advocates and patrons. His frequent and liberal contributions to our funds, and his readiness at all times to vindicate the principles and advance the usefulness of the Society, furnished unequivocal evidence of his interest in our cause.”

Francis told Baptist Press the Sunday School movement under Key and other early leaders “played no small role” during America’s first century in raising up a citizenry that was “both moral and literate.”

Ashley Clayton, a vice president at the Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee, said Sunday School once again could contribute to a spiritual renewal in America.

“The reason for that,” Clayton told BP, “is Sunday School is not just a leader or preacher. It becomes an army, from preschool all the way through your oldest adults, that has the potential of reaching more and more people.”

Sunday School classes, Clayton said, are “high-leverage events” because they include Bible study, fellowship and opportunities for all attendees to serve the Lord by meeting physical, emotional and spiritual needs.

As in Key’s day, Sunday School maintains unique ministry power in America, Clayton said.

“Americans tend to be socially oriented,” he said, “and because of that, the small groups of Sunday School provide a great platform” to reach and disciple them.