CHICAGO (RNS) — With a roll of the dice, John Scalzi sealed his fate.

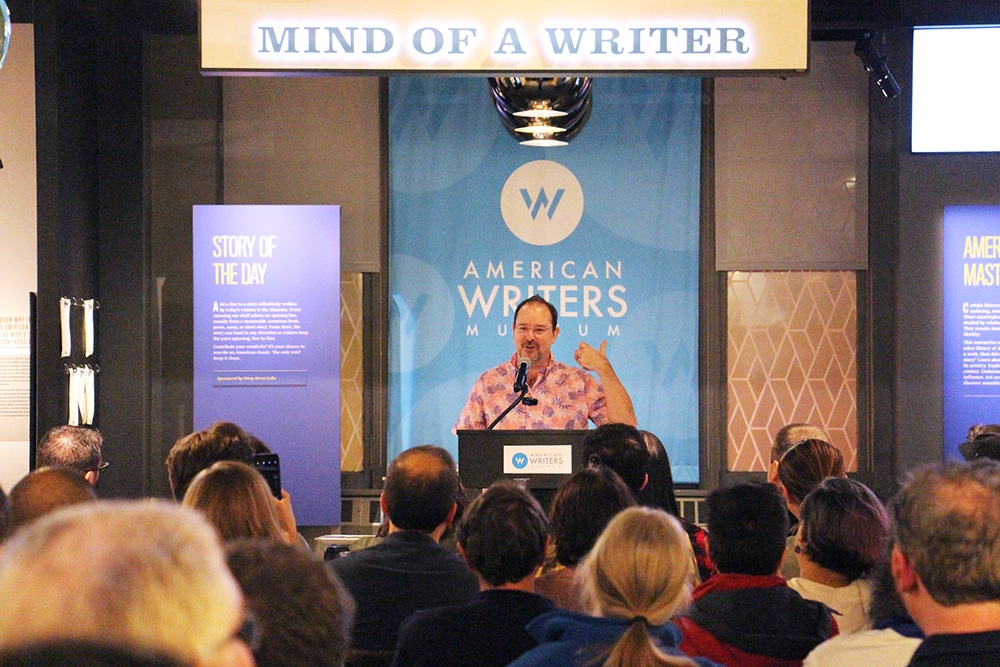

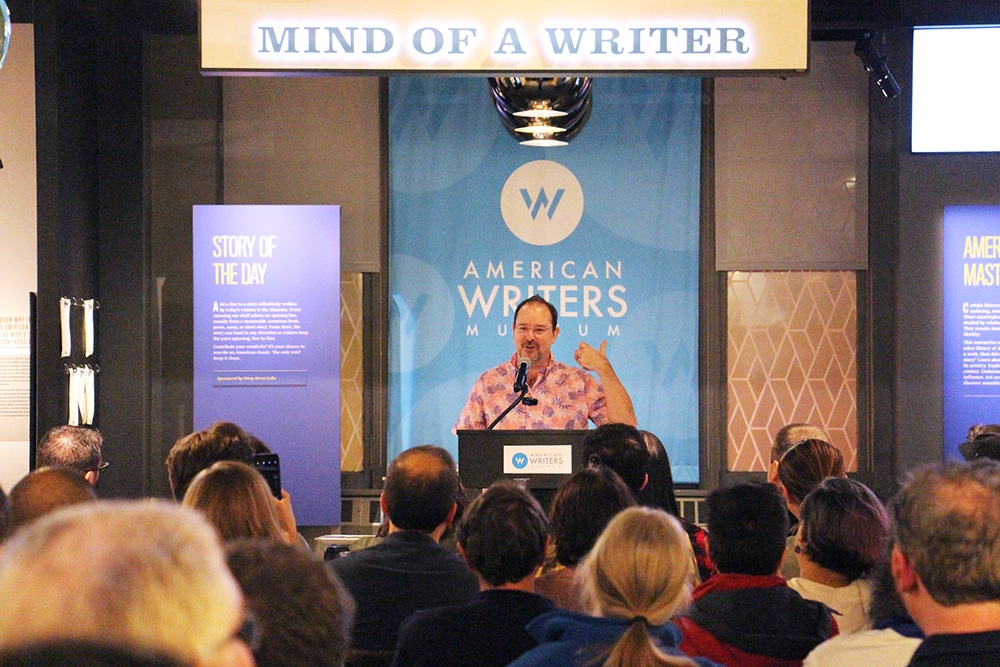

At his appearance in late October at the American Writers Museum in Chicago, the best-selling author, newspaper columnist and social media maven tossed a 10-sided die to determine what he would speak about that evening.

Science-fiction author John Scalzi speaks about his new book, “The Consuming Fire,” on Oct. 22, 2018, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan MillerSometimes it’s explaining the meaning of life. Sometimes it’s how he wrote his latest science-fiction novel, “The Consuming Fire,” in two weeks.

Science-fiction author John Scalzi speaks about his new book, “The Consuming Fire,” on Oct. 22, 2018, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan MillerSometimes it’s explaining the meaning of life. Sometimes it’s how he wrote his latest science-fiction novel, “The Consuming Fire,” in two weeks.

Sometimes it’s even preaching. During an appearance at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Fort Collins, Colo., to talk about his new book, Scalzi, a self-described agnostic, preached on Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount from the book of Matthew.

It’s a passage that speaks to him — because it asks why we do what we do.

“Even as an agnostic, to ignore the wisdom of religious teaching, to ignore the fact that so many people are religious, just doesn’t make sense,” he told Religion News Service.

Religion doesn’t just show up in Scalzi’s book tours. It also plays a role in many of his books — which look at themes like reincarnation, predestination and the role of overzealous missionaries, along with examining the good and evil that religion can do in the universe.

And that’s not unique to Scalzi.

Religion and science fiction often intersect. They’re found in the fictional worlds of sci-fi — like the imagined religions of N.K. Jemisin’s Hundred Thousand Kingdoms or the Jewish faith of mathematician-turned-astronaut Elma York in Mary Robinette Kowal’s Lady Astronaut series — as well as in the lives of its authors, like theologian C.S. Lewis, who also wrote a Space Trilogy, or sci-fi writer turned Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard.

There’s a simple reason for that, Scalzi said during a panel on sci-fi and religion at the Religion News Association conference in September in Columbus, Ohio.

“The reason I think there is religion in science fiction is because there are people in science fiction,” he said.

John Scalzi, left, participates on the panel “Close Encounters of the God Kind: Religion in Science Fiction” during the 2018 Religion News Association Conference on Sept. 13, 2018, in Columbus, Ohio. Kimberly Winston, right, moderated the panel that also included James McGrath, second right, David Williams and Farah Rishi. RNS photo by Kit DoylePeople always have looked to both religion and science fiction to imagine the future and examine the present, said James McGrath, the chair of New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University in Indianapolis. McGrath, who served on the panel with Scalzi, has taught classes on religion and science fiction.

John Scalzi, left, participates on the panel “Close Encounters of the God Kind: Religion in Science Fiction” during the 2018 Religion News Association Conference on Sept. 13, 2018, in Columbus, Ohio. Kimberly Winston, right, moderated the panel that also included James McGrath, second right, David Williams and Farah Rishi. RNS photo by Kit DoylePeople always have looked to both religion and science fiction to imagine the future and examine the present, said James McGrath, the chair of New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University in Indianapolis. McGrath, who served on the panel with Scalzi, has taught classes on religion and science fiction.

“Stories about attempts to create artificial beings … stories about beings from up there coming and visiting down here and people from down here possibly being caught up there go back to ancient times — go back as far as we can trace human storytelling,” McGrath said.

Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” published 200 years ago this year, is often viewed as the first science-fiction novel, McGrath said. It’s the story of a scientist playing God, a now-common trope in the genre.

Before that, there was the story of the Golem, a creature made from inanimate materials and brought to life in Jewish folklore, he said. And there’s a long history of “looking up in the sky and wondering about our place in the cosmos” captured in Psalm 8.

Farah Rishi, who has written about science fiction in Islam and will release her first sci-fi novel in fall 2019, pointed to science-fiction tropes in the Quran, as well.

The first sura describes Allah as “lord of the worlds,” she said during the panel. That “leaves a lot of room for creativity, for speculation.”

She also recounted an Islamic story of the seven sleepers who escape religious persecution by hiding in a cave and emerging hundreds of years later. That’s essentially a story about time travel, she said.

It’s a tradition she said has continued through the real-life science of the automatons of al-Jazari to recent works of science fiction and fantasy like the new Ms. Marvel comics and “Frankenstein in Baghdad.”

For many Muslims, Rishi said, reading widely — including science fiction — is an “unspoken tenet” of Islam, a religion founded, she said, with the angel Gabriel’s command to the prophet Mohammed to read.

And science fiction allows readers to imagine a better world.

“It’s an act of self-care to imagine a world in the near future where Muslim people exist and have relevance that is something beyond terrorism or something beyond violence,” she said.

The Rev. Wil Gafney, associate professor of Hebrew Bible at Brite Divinity School in Fort Worth, Texas, uses science fiction in the classroom.

Gafney has used “Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus” by Orson Scott Card, a book about a group of scientists who travel back in time to stop the conquest of indigenous peoples in North America, to discuss the idea of conquest in the biblical book of Exodus. She’s used “The Sparrow” by Maria Dora Russell, about a Jesuit priest who experiences “hell on several planets” after being sent as a missionary to aliens on another planet, to discuss suffering in the book of Job.

“Science fiction, for me, is inherently theological,” she said.

Hugo Award-winning author Kowal imagines an alternate timeline in her Lady Astronaut series in which Earth moves to colonize the moon and Mars after a catastrophic meteor strike in the 1950s. Kowal, who is Christian, said she made her protagonist Jewish not because she wanted to explore religion but rather because she did not want to ignore it.

“What I wanted to do was give her the same emotional life that all of my other characters have,” she said.

Science-fiction author John Scalzi speaks about his new book “The Consuming Fire” on Oct. 22, 2018, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan MillerReligion plays a huge role in the Interdependency series by Scalzi, who is friends with Kowal, for similar reasons — because “religion tends to be a supporting strut in civilization, period,” he said.

Science-fiction author John Scalzi speaks about his new book “The Consuming Fire” on Oct. 22, 2018, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan MillerReligion plays a huge role in the Interdependency series by Scalzi, who is friends with Kowal, for similar reasons — because “religion tends to be a supporting strut in civilization, period,” he said.

Scalzi’s Interdependency is an interstellar empire founded on a prophecy and connected by a stream between star systems. Its leader is head of both the empire and its largest religion. When the connections between planets collapse, she uses the church as a “tool for doing good.”

“The good, in this case, is saving as many people as possible from this natural collapse. That is an inevitable. It’s going to happen. How do we save as many people as we can, even if and when the empire itself is falling?” Scalzi said.

A positive portrayal of religion can be surprising for some to see in science fiction, Scalzi acknowledged. But he said it’s part of the complexity of humans, both in real life and on the page.

Religions ultimately are about people. In the hands of some leaders, religion is a profound source of good, he said. In the hands of others, it can be evil.

And so is science fiction.

The genre is “about people dealing with a different time, dealing with different technology,” Scalzi said. “But they are still people, and the religious impulse is never going to go away.”

And science-fiction writers can’t ignore it.

“When 5 billion people out of 7 billion very strongly have professed religious belief of some sort or another, to ignore it, minimize it or just say it doesn’t matter is foolish,” he said.