New Orleans Saints and New England Patriots players form a prayer circle after an NFL football game in New Orleans on Sept. 17, 2017. (AP Photo/Bill Feig)

(RNS) — If you’ve never heard of New England Patriots “character coach” Jack Easterby, it’s not for lack of media attention. Ever since ESPN’s Seth Wickersham published a feature article on him in 2015, Easterby’s profile has risen, with stories in the Boston Herald, USA Today, Patriots.com and more. With the Patriots in the Super Bowl yet again, this week has brought another round of attention to Easterby.

He may not be a household name, but in a football culture filled with outspoken evangelicals, Easterby stands out from the pack.

His basic story is easy enough to follow.

Easterby started out as a Fellowship of Christian Athletes campus director and chaplain/”character coach” for the men’s basketball team at the University of South Carolina and then served as a chaplain for the Kansas City Chiefs. Bill Belichick and the Patriots scooped him up in 2013 to take on the somewhat nebulous chaplain-like role as “character coach” in the wake of star tight end Aaron Hernandez’s arrest.

While every NFL team has a chaplain, Easterby is unique. A typical team chaplain is a full-time minister to a congregation, serving as the chaplain in a voluntary role on the side.

But Easterby is on the Patriots’ payroll, with an office at the team’s Foxborough headquarters, an ever-evolving set of responsibilities, and a voice in personnel evaluations.

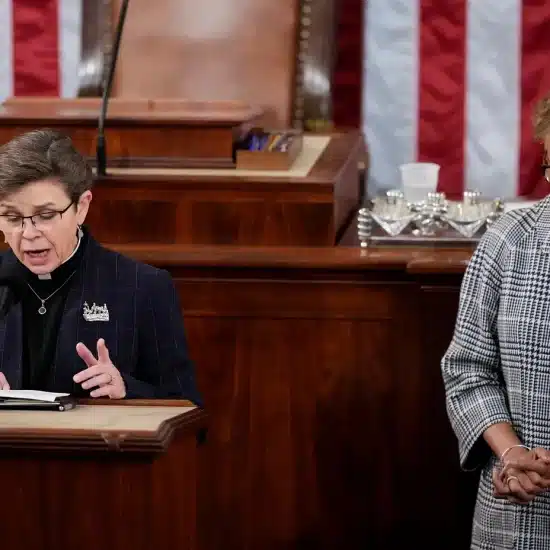

New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick, left, talks with team chaplain Jack Easterby during practice on Jan. 30, 2015, in Tempe, Ariz. The Patriots play the Los Angeles Rams in the Super Bowl on Sunday, Feb. 3, 2019. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

Still, if we put his story in historical perspective, Easterby seems like less of an outlier. In some ways, he’s merely the next step in the evolution of a movement that began fifty years ago to institutionalize evangelicalism within professional football, a movement spearheaded by the original evangelical sports chaplain, Ira Lee “Doc” Eshleman.

The founder of “Bibletown, USA” in Boca Raton, Florida—a combination of various ventures including a church, real estate enterprise, vacation spot, and Bible study conference center—Eshleman began looking for new projects in the mid-1960s.

Around that time, he came into contact with a group of NFL players who were involved with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. A few of the athletes — led by Buddy Dial and Bill Glass — had recently initiated player-led pregame chapel services on their teams.

Searching for a way to reach American youth in the midst of the tumult of the 1960s, Eshleman hatched a plan: He would make his way into the ranks of pro football by serving as an unofficial chaplain while building a network of pregame chapel services for every NFL team. Independently wealthy thanks to his real estate investments in Boca Raton, he would pay his own way, asking for nothing but a few moments before breakfast on game day and the chance to build relationships with players and coaches who, in turn, could reach American youth.

Declaring himself the “Unofficial Chaplain of the Sports World,” Eshleman launched his new career in 1967, leading a pre-game chapel service for the Atlanta Falcons. Wearing a white turtleneck sweater, red Bombay blazer, and blue Jaymar slacks, Eshleman quickly ingratiated himself to the league, holding services that season for the Baltimore Colts, Dallas Cowboys, and Washington Redskins, among others. By the end of the year, he had even won over Vince Lombardi, who allowed Eshleman to hold a voluntary chapel on the morning of the Packers’ Super Bowl II matchup against the Oakland Raiders.

“Man universally is searching for some definite answers to such great issues as life and death, time and eternity,” Eshleman’s message that morning began, before ending with a call for players to invite Christ into their hearts as “Savior and Lord.” (The Packers, incidentally, won the game 33-14.)

Over the next few years, Eshleman became a fixture in the NFL, flying around the country to host pregame chapel services on Sundays and facilitating the development of player-organized chapel services on as many teams as possible.

Thanks in large part to Eshleman’s efforts, by 1976 every team in the NFL had regular pre-game services. By then, Eshleman was no longer the only prominent chaplain on the scene, as other entrepreneurial ministers entered the circuit.

Tom Skinner, an evangelist, author, and leading voice for African American evangelicals, became closely associated with the Washington Redskins, while Billy Zeoli, president of evangelical media company Gospel Films (and close friend of Gerald Ford), became especially popular with the Dallas Cowboys. Even so, Eshleman’s work in the late 1960s paved the way for the institutionalization of pre-game chapels — and thus the need for team chaplains — in the NFL.

Jack Easterby rode this chapel system into the NFL with the Kansas City Chiefs. But Easterby is more than a chaplain. He is charged with promoting a culture of positivity and encouragement and helping the Patriots identify and cultivate character traits in players that will lead to team success.

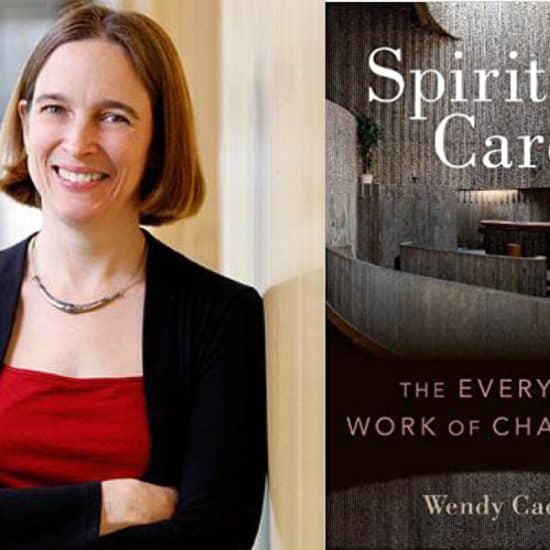

Ira Lee “Doc” Eshleman. Photo courtesy of Sports World

That role, it turns out, was also pioneered by Eshleman.

Beyond just organizing chapels, Eshleman saw himself as a spiritual counselor to the players, offering a listening ear as they confided in him about family problems, the stress of life as an elite athlete, and the ever-present dread of serious injury.

“The pro is so honest and uninhibited in discussing his problems, that it is easy to get to the core of problems and to relate them to God’s answer,” Eshleman once explained to a reporter.

As for Eshleman’s counseling system, it was derived from Campus Crusade for Christ’s “Four Spiritual Laws”:

- God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life

- Man is sinful and separated from God, thus he cannot know and experience God’s love and plan for his life

- Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for man’s sins. Through him you can know God’s love and plan for your life

- We must receive Christ as Savior and Lord by personal invitation

Eshleman pitched his counseling services as a boon to a team’s performance. While he was always quick to say that prayer and faith did not guarantee victory on the field, he also claimed that a player with faith would be able to deal with pressures and anxieties more effectively, which in turn would lead to mental focus, which in turn would improve the odds of success.

Since “what happens at home can affect a man’s performance on the gridiron,” he explained, his “ministry to the individual player can even show up on the scoreboard.”

Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry bought in.

“The effect that faith has is to make a person able to reach his full potential,” Landry told a reporter at a conference hosted by Eshleman. “This is absolutely basic to an athlete. The real hangups, the doubts and insecurities, are mental.”

Joe Robbie, owner of the Miami Dolphins — one of Eshleman’s favored teams — offered a similar sentiment.

“I wouldn’t think to say religion is the reason we’re in the Super Bowl,” he said in 1973, “but it certainly helps in building a winning attitude.”

Numerous players, including Norm Evans, Carroll Dale, Harry Jacobs, and Lem Barney, sang Eshleman’s praises as well.

To be sure, Eshleman was not universally loved in the NFL.

There were more who did not embrace his evangelical convictions than those who did. Yet, even those who poked fun at him often did so with a smile.

In “North Dallas Forty,” a 1973 expose of the Dallas Cowboys written by former player Peter Gent, Eshleman shows up as “Dr. Tom Bennett,” a minister who was “everybody’s pa.” Gent’s description of Bennett dripped with sarcasm, yet he also wrote that “Doc was a pretty good sport and quite fast on his feet,” a man who “laughed good-naturedly” after two players told him they missed the pregame chapel because they were busy fooling around with a woman at their hotel.

By combining his outspoken evangelical beliefs with a laid-back approach to those outside the evangelical fold, Eshleman could present himself as broad-minded enough for the diversity of an NFL team.

More importantly, by presenting himself as a spiritual expert — one who “weighs and evaluates each player’s spiritual record, just as a coach considers his on-the-field record” — and by linking his spiritual services to a team’s success, Eshleman helped to legitimize his evangelical ministry within the NFL.

Today, Jack Easterby mirrors this approach.

Not as flamboyant as Eshleman and far less likely to drum up publicity, Easterby is nevertheless unapologetically evangelical. His organization, The Greatest Champion, aims to “see the platform of athletics used as a world-changing network that communicates the message of Christ and his principles.”

At the same time, Easterby — like Eshleman — seems to be able to connect with players and coaches who do not share his evangelical beliefs. And he has managed to convince NFL executives and coaches that his faith-based counseling and mentorship benefits the team as a whole.

Through his “character coach” position with the Patriots, Easterby embodies the logic that Eshleman put forward fifty years ago: that tending to the spiritual needs of NFL players can improve a team’s performance.

“Few people can laugh off the message of Doc, especially in view of the success of his ministry,” one of Eshleman’s associates declared in 1972. “The product must be good. A lot of people are buying.”

Paul Putz is a historian who specializes in the history of sports and religion. He blogs at sportianity.com.