Vice President Mike Pence, right, administers the Senate oath of office to Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., during a mock swearing in ceremony in the Old Senate Chamber on Capitol Hill in Washington, on Jan. 3, 2019, as the 116th Congress begins. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

(RNS) — This fall, voters in the Midwest elected two Muslim women to the U.S. House of Representatives, the first female members of their faith to enter Congress. The same day, Arizona elected Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, who, while not the first of her kind, is even rarer: Sinema is the only person serving in Congress to identify as religiously unaffiliated — putting her in a caucus of less than 0.2 percent of the lawmaking body.

Even after adding in two representatives who identify as “Unitarian Universalist” and the eighteen who “Don’t know/refused,” just over 2.5 percent of those serving in Congress attest to an untraditional theistic faith or no faith at all.

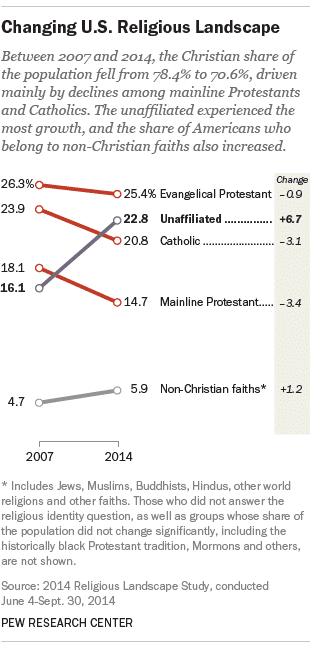

Compare this to the general American public: fewer than half consider religion to be an important part of their lives. More pertinently, in a landmark 2015 Pew Research Center survey titled “America’s Changing Religious Landscape,” 22.8 percent of respondents identified as “religiously unaffiliated.” Of Democratic voters, the unaffiliated were the single largest “faith” group, at 28 percent. Unaffiliated Republican voters represented just 14 percent of respondents.

If an increasing number of people are not affiliating with a religious group and attendance at religious activities is believed to be in decline, why aren’t elected officials’ religious affiliations reflecting the trend?

As the Pew numbers suggest, the divisions in our politics may be to blame.

The party divide reflects a values divide. While the majority of both Democratic and Republican voters may agree that religion’s influence on American life is decreasing, Democrats are much more likely to accept that trend. For many Republicans, the decline is seen as a problem that should be corrected.

If the majority of the GOP’s base, which identifies as either Christian or Mormon, sees the waning influence of religion on American life as a disaster in the making, it follows that identifying as religiously unaffiliated could by itself be a deterrent to voting for a candidate — even if the candidate’s political positions are in sync with the voter’s.

If the majority of the GOP’s base, which identifies as either Christian or Mormon, sees the waning influence of religion on American life as a disaster in the making, it follows that identifying as religiously unaffiliated could by itself be a deterrent to voting for a candidate — even if the candidate’s political positions are in sync with the voter’s.

On the other side, while the number of non-religious voters actively involved in politics is growing, it’s unlikely that non-religious citizens would choose not to vote for a candidate whose faith determines their positions (except for those few whose antipathy toward religion actually drives their politics). Data prior to the 2018 midterms indicated strongly that policy — not religion — was top of mind for voters.

But any reasonable politician may be disinclined to identify as unaffiliated because of the public perception of atheists.

What is that perception? Atheists — ironically, given the state of civil discourse in our current Congress — have a reputation for inciting fierce debate. They are seen as killjoys who press towns and villages to take down nativity scenes and make demands about prayer in schools. Not content simply to aggravate those who cherish religious traditions, the perception goes, they actually poke fun at people’s religious beliefs.

This perception results in anger toward nonbelievers of all varieties and a tendency to paint all who do not profess traditional theistic beliefs with the same brush.

But there are many ways to have faith beyond traditional theism. The members of the Ethical Culture Society of Westchester in New York, where I am a clergy person, focus on how to live an ethical life rather than worship a particular god or gods. As is likely true of those who attend any of the 23 member societies of the American Ethical Union (AEU), we describe ourselves as agnostic or humanistic, since we don’t profess belief or non-belief in a deity. Few of us would describe ourselves as atheists, at least in part because we bristle at the thought of being defined by an absence of belief.

At the same time, our avoidance of the term is also doubtless because of the emotional reactions to what others think atheists are.

For politicians, the negative associations are compounded by the idea that disbelief is unpatriotic. Being branded an atheist also incurs suspicions in the minds of voters that the politician has no moral center, lacks integrity, and is probably dishonest.

In fact (though facts seem to have little effect on people’s attitudes toward non-belief), atheists are, on the whole, less nationalistic, prejudiced and authoritarian than the average American. What’s more, we atheists, agnostics, humanists and freethinkers tend to put a high value on scientifically objective truths.

As the 2016 presidential election demonstrated, however, personal integrity is not a criterion for a substantial number of voters determining their choice of candidates. The key factor, when push comes to shove, is not honesty or objective fact but, rather, alignment with one’s attitudes and emotions.

Perhaps the growing percentage of the religiously unaffiliated among the voting public will encourage candidates to focus their attention on morally significant concerns and to grapple more deeply with the urgent matters before us. Atheists can do that as well as anyone.

As importantly, the nation would be better served to have a variety of religious points of view represented in Congress. As a country founded on the principle of religious freedom, we should actively encourage — not discourage — openness in our elected officials when it comes to their beliefs. And we would finally have a Congress that looked like America.