Before the triumph of Easter Sunday, where is God on that Saturday? Image by Jeff Jacobs from Pixabay

Easter is one of the holidays that has the most build-up to it, as far as religious observances go. There is Fat Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and, of course, Easter Sunday. But what do we seemingly neglect to acknowledge each year? The day between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. The Saturday that Jesus was dead.

No, I do not think that it needs its own title like “Sad Saturday” or “Sackcloth Saturday” (or what some people call it, “Black Saturday”). Instead, I believe that the hopelessness, fear and evil of that day should be addressed.

This year, the Saturday before Easter falls on April 20.

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20. The Columbine High School shooting occurred 20 years ago on April 20, 1999. Drug users often associate the date and time (4:20 p.m.) with smoking marijuana.

Christians and society alike want to see that good came out of bad. They want the answer to the question: Where is God?

When taking a timed test, it is strategic to skip over the hard questions where we are unsure of the answer. Maybe it is this reason we tend to skip over one of the most relatable days of Easter Week: Saturday. The day Jesus was dead. The day so full of questions and uncertainties that it is easier to skip to the parts we know more about.

Saturday Faith

The disciples did not help us out in understanding what living that Saturday was truly like. The only writing we have from that day comes from Matthew in chapter 27:62-66 when he writes that Pontius Pilate ordered guards to stand at Jesus’s tomb so the disciples could not steal the body to make the promised resurrection appear to have happened. But the disciples didn’t appear at the tomb that day.

We must remember that Saturday was the Sabbath day, so this could be one reason that no more detail was written regarding the day Jesus was dead. The other reason is likely that it was the day filled with uncertainty, waiting and nervousness. The Savior that the disciples had left everything to follow was dead. Instead of writing divinely inspired scriptures, perhaps the disciples were just left wondering: Where is God?

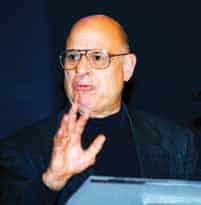

“The disciples had to be scared,” said Cy McMahon, lead pastor of Granite Church in northwest Iowa. “On Friday, after the crucifixion, it was dark and therefore unsafe to go out. On Saturday, it was the Sabbath so they had their day of rest. They had to wonder if they were next to die. If Jesus would really return. They were in a day where everything seemed lost, sad, uncomfortable and beyond repair.”

Cy McMahon

McMahon found the Lord after college and was delivered from alcoholism through his faith. Although finding the Lord made life meaningful for McMahon, it did not make it easy.

“There is nowhere in the Bible that says that being a Christian is easy. Most of the people in the Bible endured trying lives and terrible deaths. When bad things happen, it is often questioned why such an awful thing can happen to a good person. But we were never promised an easy life of luxury. We were told to take up our cross and follow him,” said McMahon.

McMahon has endured a great number of trials in his life. His wife lost her leg due to a doctor’s mistake. A child they cared for from her day of birth and pursued adopting was stripped from their home by the teenage birth father when the baby was over a year old.

“I still remember pulling in the driveway after receiving the call that we had lost the adoption. [The baby] was still in our house, still in our care, but we had to give her up. I remember crying in that moment, not in anger at God but in extreme sadness,” said McMahon.

The verse that got his family through these times of sorrow was John 14:27: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.”

McMahon said that most of his faith has been a “Saturday faith.”

The disciples were a unique group who were able to literally follow in Jesus’s footsteps. They also had to endure his death, but they were blessed to also celebrate the resurrection. But most Christians live a Saturday faith. The day where there was nothing more to do than to wait, to hope, to wonder. The day to ask, “Where is God?”

Max Lucado wrote, “Saturday’s silence torments us. Is God angry? Did I disappoint him? God knows Jesus is in the tomb, why doesn’t he do something? Or, in your case God knows your career is in the tank, your finances are in the pit, your marriage is in a mess. Why doesn’t he act? What are you supposed to do until he does? You do what Jesus did. Lie still. Stay silent. Trust God.”

Being still. That sounds like an easy task. It takes no talent, no special training. You just need to do nothing. Yet, that is one of the hardest assignments to ace. Being still means that you have no control. You have no say. You have no strategy. But God tells us time and time again to be still.

“The LORD will fight for you; you need only to be still” (Exodus 14:14).

“Be still before the Lord and wait patiently for him; fret not yourself over the one who prospers in his way, over the man who carries out evil devices!” (Psalm 37:7).

“For God alone, O my soul, wait in silence, for my hope is from him” (Psalm 62:5).

So how do we stay still and trust the Lord to fight for us in the most uncertain or tragic of times?

My late friend Judita Hruza, a Holocaust survivor, gave me the simplest of advice: Count your breaths.

I met Hruza when she served as a keynote speaker at a patriotic forum hosted at College of the Ozarks in Branson, Mo., in April 2012. After she spoke, I was privileged to have the opportunity to get to know her. During our conversation she said, “Your children will never know a Holocaust survivor. Promise me that you will share my story.”

Judita Hruza (left) and Pamela Lowe

Hruza was born in Czechoslovakia, near the Hungarian border, to a middleclass Jewish family. In 1938, her village was gifted to Hungary by Hitler, and then anti- Semitic laws regulated her family. In 1942, Hruza’s grandmother and uncle were taken to Auschwitz and her grandfather died in a freight car on the way there.

Hruza and her brother were attending school in Budapest on March 19, 1944, when they heard of the German occupation. Within two hours, she and her brother went to the train station in hope to travel home to be with their parents — but they were denied passage because they were Jews. Two months later, her parents were deported to Auschwitz where they died.

In October 1944, a 20-year-old Judita Hruza was told to report to work at a sports stadium with a three-day food supply, warm clothes and shoes. This call to “work” was actually the beginning of a death march through Budapest, Western Hungary and Upper Austria. After months of fighting for her life, eating each crumb of molded bread she could find and killing hundreds of lice on her body each night so she would wake another day, Hruza was forced to walk up a steep hill amongst gunfire.

“Suddenly I just wanted enough time to take 20 breaths. I thought of the zillions of breaths that I had taken — without a thought — during the last 20 years. Now I begged for just 20 more breaths. The shooting lasted for 40 minutes. Five hundred people were killed; two hundred survived,” wrote Hruza in the book “Doctors in Peril.”

On April 15, 1945, Hruza was led to Gunskirchen Death Camp. On May 4, 1945, Gunskirchen was liberated by the US Army and she was freed. Throughout her life, Hruza has been asked how she managed to survive the food shortages, the lice, the horrors, the shootings and the selections for execution.

“The odds were against me,” she wrote. “Death came in so many forms and so frequently that an individual’s chance of survival was negligible. In Gunskirchen Death Camp prisoners died at a minimum rate of 200 a day. If the U.S. Army had arrived six weeks after its actual liberation date, they wouldn’t have found a single survivor.”

Twenty years after she was liberated, Hruza took her children (ages 8 and 13) back to the steep hill in Eisenerz where she had pleaded to take just 20 more breaths. There was no memorial or sign to commemorate the hundreds that had lost their lives in that very spot, just a sign advertising a circus.

Hruza believes that her “Saturday” was the Holocaust.

“I have habits that originated in the Holocaust,” she wrote. “I have trouble throwing out food. I don’t take simple pleasures for granted, I save them. Whenever I take a shower, I am delighted that it’s warm water, not the October rain, that is running down my body. Whenever I am out in the street on a cold, rainy, windy day, I am elated, elated because soon I will be in a dry, warm, safe place.”

Is she thankful that she was in a death march and taken to a death camp? No. But did she let the darkness of that time remind her of the true light she experienced after her liberation? Yes.

“With each breath you take, hope spreads. As long as you can breathe, you have hope. When something bad happens, count your breaths,” she urged.

Hruza met one of the soldiers who helped liberate her from the death camp. He shared with her that he regretted that they could not have liberated the camp sooner, knowing that it would have saved so many more lives. But liberation wasn’t a job that only man could have performed. Where was God?

Not Sunday Yet

Baptist author and preacher Tony Campolo likes to tell a story of a “preach off” where he learned five powerful words: It’s Friday, but Sunday’s coming!

Tony Campolo preaching “It’s Friday, but Sunday’s coming!” in Liberty, Mo. on April 4, 2009. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

“Friday, Jesus was dead on a cross. But that is because it was Friday — Sunday’s coming,” Campolo says. “Friday, things have been so they should be. You can’t change things in this world, but I’m here to give you the good news. It’s only Friday. Sunday’s coming!”

It’s inspirational, but skips over Saturday. The disciples did not know that Sunday was coming. What they knew was that their lives, as they knew them, had come to an end. The man they loved, set their lives aside for, worshipped and adored had been murdered. He was dead. Where was God?

The book of Psalms is full of laments. There are actually more psalms filled with laments than any other type of psalm. So, why did I learn only about the psalms of Thanksgiving in Sunday School and church services? Is it because spiritual leaders fear answering the question: Where was God?

What if our churches don’t skip over a Saturday faith? A faith that says that we are finite beings who will never understand an infinite God. A faith that says that we don’t know all of the answers. A faith that admits to not knowing how the death of a child or a terrorist attack could possibly be a blessing from the Lord or why to not knowing why God would allow it to occur. Isn’t it then that Christianity becomes more powerful? When faced with the hurt, pain and utter shock of terrible events that Christians feel comfortable with lamenting to God because they know God cares about their pain?

The psalmists thought so.

“I cry aloud to the Lord; I lift up my voice to the Lord for mercy. I pour out before him my complaint; before him I tell my trouble. When my spirit grows faint within me, it is you who watch over my way. In the path where I walk people have hidden a snare for me. Look and see, there is no one at my right hand; no one is concerned for me. I have no refuge; no one cares for my life. I cry to you, Lord; I say, “You are my refuge, my portion in the land of the living. Listen to my cry, for I am in desperate need; rescue me from those who pursue me, for they are too strong for me. Set me free from my prison, that I may praise your name. Then the righteous will gather about me because of your goodness to me” (Psalm 142:1-7).

And we don’t have to read very much news to see the pain all around us.

In November 2018, a wildfire swept through Paradise, Calif. It claimed the lives of at least 85 people and destroyed 18,804 buildings. Shane Edwards’s house was incinerated in the fire and he posted a photo of the only remaining sign that he’d lived there — his brick hearth and chimney. As CNN reported, Edward’s friend Shane Grammer saw beyond the destruction depicted in the photo. He saw a blank canvas.

Grammer asked Edward for permission to paint a mural on the remaining bricks as a way to make beauty out of the ashes. Grammar painted the face of a woman on the hearth and captioned it with the scripture reference Isaiah 61:3-4.

“To appoint unto them that mourn in Zion, to give unto them beauty for ashes…”

Shane Grammer’s portrait of Jesus on the baptismal in the ruins of Hope Christian Church in Paradise, Calif. (Terence Duffy)

When neighbors of Edwards saw the mural, they asked if Grammer could make their rubble into a work of art as well. So, he returned to burned Paradise and painted over 20 murals on the debris, including on the remains of the baptismal in the destroyed Hope Christian Church. At times he painted portraits of victims or survivors. At the church, he painted Jesus.

“I did it in an hour,” he told CNN about the Jesus painting. “The spray paint just melted into the residue and made this symbol, both for people thanking God for saving us and asking, ‘God, why did you do this?’”

Although the murals do not bring back the lives lost or the property destroyed, they have become a drop of beauty in the ashes. And perhaps Grammer’s work hints at an answer to the age-old question of “where is God?”

This is an excerpt from the full article appearing in the April 2019 issue of Word&Way.