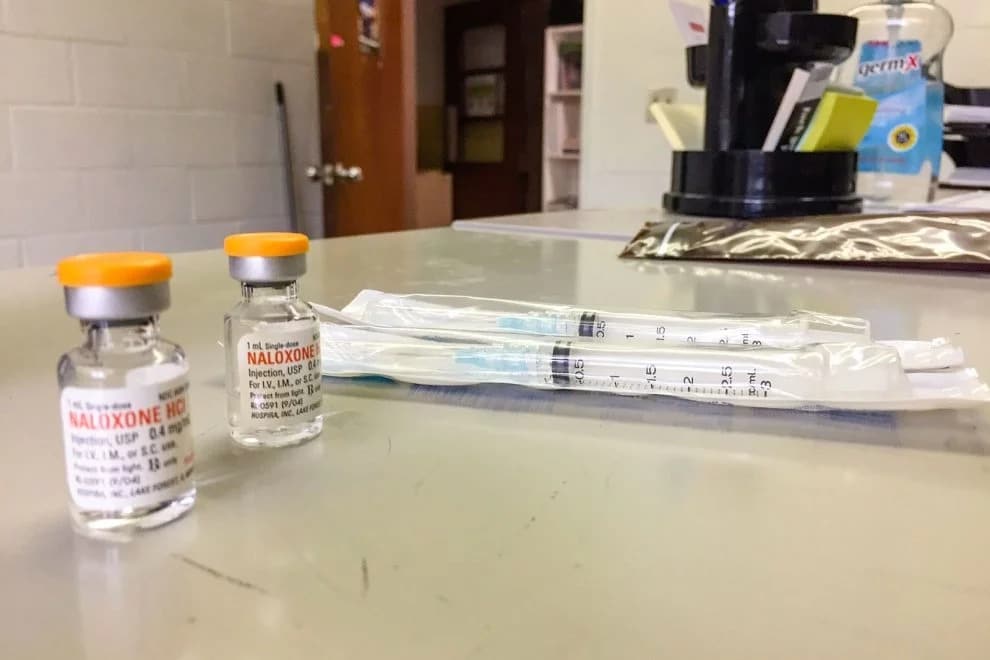

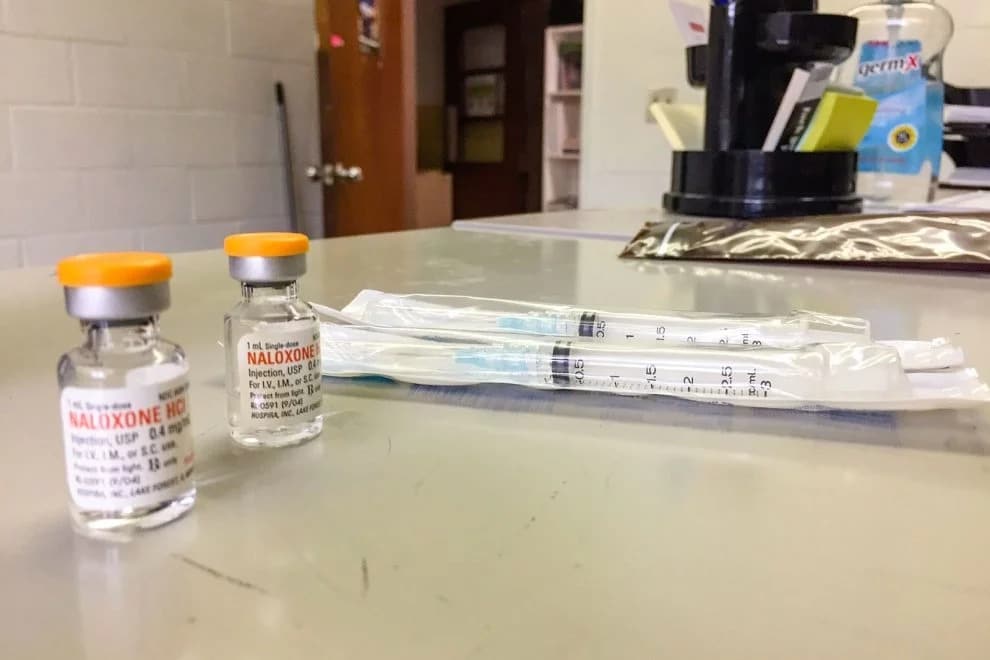

The Twin City Harm Reduction Collective distributes naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug, seen in the basement of Green Street United Methodist Church in Winston-Salem, N.C., on June 6, 2019. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. (RNS) — The Rev. Sarah Howell-Miller, a United Methodist minister, once opposed needle exchange programs for opioid addicts — a stance shared by legislators in some three dozen states. The idea of giving addicts the means to shoot up was, in Howell-Miller’s word, “garbage.”

Then she fell in love with a drug user.

Howell-Miller’s husband, Colin Miller, began using heroin when he was 18, and first went to a syringe exchange when he was homeless and living on the streets of Minneapolis. He said the clinic taught him how to shoot up safely, and when he first wanted to go into detox, the exchange was the first place he turned to.

“It was this unconditional love and care they were extending to me that really resonated with me,” said Miller, who now works as a harm reduction consultant for North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services and advocates for practices such as needle exchanges.

Three years ago, Miller turned to the Rev. Kelly Carpenter, pastor of Green Street Church, with a proposal to house a clinic like the one he’d gone to in Minneapolis. In 2016, the Twin City Harm Reduction Collective moved in.

Green Street United Methodist Church in Winston-Salem, N.C., on June 6, 2019. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Today, in a room in the church’s basement, a row of black metal cabinets is stocked with nearly all the supplies a drug user might need: boxes of syringes, sterile water, cookers, cotton ball filters, rubber tourniquet bands and tiny glass bottles of naloxone, the overdose reversal drug.

The room is visited monthly by about 130 users who drop in to stock up on supplies. While they are there, they often get tested for hepatitis C and HIV, another service the clinic offers. Everything is free and confidential.

New and returning drug users are given a brown paper bag with one box of syringes and anything else they need, including toothpaste and condoms. They are only asked to give their name, date of birth, race and gender. (They may also decline.)

“This reaches the most desperate people in society — people who are out there on the streets, homeless, using drugs,” said one 25-year-old heroin user who gets his supplies at the clinic and has also volunteered there, but did not want his name used. “It’s really an important thing to have.”

Howell-Miller agrees. “I’ve heard people who have struggled with substance abuse say that for them to just walk into a syringe exchange, that’s an act of caring for themselves that perhaps they have never thought they were worthy of, and have probably been told they weren’t worthy of,” she said. “That’s a profound ministry.”

The Rev. Sarah Howell-Miller talks to the Rev. Kelly Campbell, middle, along with Colin Miller at Peace Haven Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, N.C., on June 6, 2019. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Green Street, a United Methodist church, is one of a handful of syringe exchanges housed at a place of worship across the state, and the North Carolina Council of Churches is encouraging more congregations to consider hosting them — part of a larger effort to get churches involved in stemming the opioid epidemic that in 2017 killed 1,884 people across the state, or nearly six a day.

As an approach to the opioid crisis, the welcome and dignity offered by needle exchanges fit in with Green Street’s mission.

‘This church had a long commitment to do ministry with people that other people don’t want to be in ministry with,” said Carpenter, referring to the church’s ministry to the poor and to LGBTQ people. “We’re trying to meet people where they are.”

Many churches already host 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, often providing these groups free meeting space in their buildings. Some offer Celebrate Recovery, another popular 12-step model consisting of a worship service followed by small group sessions.

But these programs, which require participants to abstain from drugs or alcohol, don’t reach everyone. As many drug users will attest, recovery is not a one-time process. Some spend years relapsing until they are drug-free. And many can’t quit. They need medication-assisted treatment, in which a doctor prescribes them a type of opioid that reduces cravings as a way of weaning them off harder, more potent opiates.

“Abstinence-based programs are really important,”said Howell-Miller. “But I think a big learning for me is that it doesn’t work for everyone. When that’s presented as the only option, it becomes isolating and even dangerous for people for whom that doesn’t work.”

Nationally, 130 people a day die from opioid overdose, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Recognizing prescription opioids’ addictive qualities, doctors are prescribing less and more people are turning to street heroin or fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid similar to morphine.

There were 70,237 drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2017, the last year for which numbers are available, according to the Centers for Disease Control. That’s a 9.6% increase from 2016.

Religious congregations have intimate knowledge of such deaths. A North Carolina Council of Churches survey found that 70% of pastors statewide said opioids had affected their congregation; the remaining 30% said they suspected it had but weren’t sure because the congregation didn’t talk about it.

Pastors, said Elizabeth Brewington, opioid response program coordinator with the NCCC, “don’t know where to refer congregants if they needed help and don’t know of resources besides AA and NA.”

The Twin City collective allows drug users to begin to take better care of themselves by using sterile equipment, getting tested for infections and forming relationships with recovering addicts and health advocates.

If nothing else, the collective provides free vials of naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, which paramedics often administer to people whose breathing has slowed or stopped after an overdose. By the collective’s count, 195 people used Narcan vials it distributed in 2018. This year, 210 have administered the drug so far, meaning that as many people have been able to reverse a life-threatening overdose.

“People know it’s a safe space where people can come and talk,” said Rachel Thornley, the program director who runs the service three days a week. “It’s not a trap. The police aren’t waiting for them.”

Still, for many, harm reduction remains a controversial approach.

When the Twin City Collective was first planned, neighbors pushed back and a city councilman objected, but ultimately the congregation was able to win over most of its critics. Last year, the collective won a $98,000 federal grant to hire staff and buy supplies. (The federal government won’t reimburse for syringes or for naloxone, but it will pay for other supplies.)

Recently, it rented a van to distribute supplies at a gas station on the edge of the city.

Rachel Thornley, program director for the Twin City Harm Reduction Collective housed at Green Street Church in Winston-Salem, N.C., poses for a picture at the church on June 6, 2019. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

It gives all its participants a card with the North Carolina statute that allows anyone to carry syringes and injection supplies and shields them from prosecution.

At a meeting in Winston-Salem last week, two dozen clergy — Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians — sat around tables and listened to Miller tell his story and consider a host of ways congregations can get involved.

Several asked what was the difference between enabling drug users and caring for them. Howell-Miller offered that there was no hard line.

“It’s really difficult to figure that out,” she said. “Having someone to talk to can help.”

But for addicts like the 25-year-old heroin user who takes advantage of syringe exchanges, the need for more such compassionate caring is obvious.

“I don’t really know how people can conscientiously object,” he said. “The only thing it does is provide stability for people who otherwise have to resort to crime. It lets them have some semblance of normal life.”