Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — I first became aware of the power of Christian nationalism last year, during an interview at the Evangelicals for Life Conference in Washington, D.C., a gathering that coincided with the March for Life, a large, predominantly conservative Christian rally to oppose abortion and urge the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

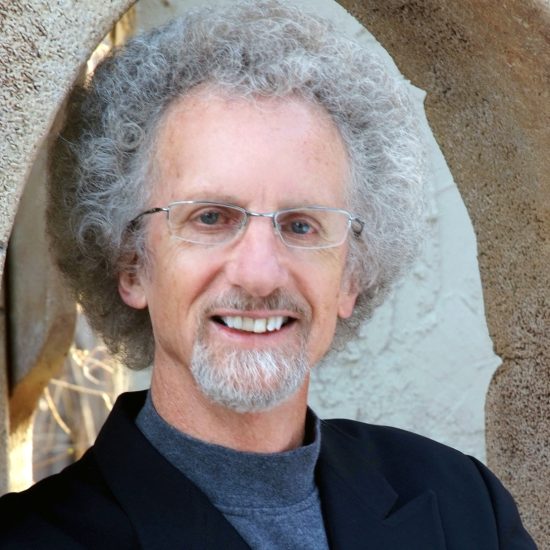

My conversation partner that morning was Dean Inserra, a prominent conservative evangelical pastor, the founder of City Church in Tallahassee, Florida, a Liberty University grad and an advisory member of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Inserra told me about a term from Southern Baptist theology that describes the current moment in American politics and religion. “In this linking of nationalism and Christianity, we are forgetting about the message of Jesus. … When we do that, we have a gospel distortion.”

Dean Inserra. Photo courtesy of City Church

A gospel distortion is the idea that another ideal is impeding the truth of the gospel. Inserra said the gospel distortion in the SBC during and before Trump’s presidency has its roots in Christian nationalism.

“We have to be Christian first. If you are American first, Jesus will be at odds with you,” he said. “Patriotism is not a fruit of the Spirit. It’s idolatry on the Fourth of July.”

Inserra pointed to national holidays that receive as much attention in the SBC as Christmas and Easter. “I say there are different high holy days in the Southern Baptist Church. Some churches have Pentecost and Epiphany. We have the Fourth of July, the Sunday closest to Veterans Day, the Sunday closest to Sept. 11. You go to a Southern Baptist Church on the Fourth of July, you’d think you were at a baseball game, eating a hot dog.”

I believe — with my conservative Christian brothers and sisters — that Christians have an essential role to play in modern-day America and that the Bible has something to say about politics.

But what Inserra said had stunned me, and to learn more I determined to go to a Southern Baptist church in Dallas on Fourth of July weekend. I wanted to hear which would speak louder: Jesus or America.

In my years as a pastor and churchgoer, I’ve attended my share of impressive megachurches, so at first glance, Prestonwood in Plano didn’t look too different. The massive worship center and surrounding buildings rose like a mirage miles from the interstate, down the broad roads of suburban Texas.

Still, as I turned into the enormous church parking lot, I noticed a distinguishing feature. In front of the worship center, off the main road, was a football stadium as large as any high school stadium I’d reported from as a sportswriter in football-crazy South Florida. “Five-time state champions,” read the banner: 2017, 2015, 2010, 2009 and 2005. In Friday Night Lights territory, this was no small feat.

Prestonwood Baptist Church, right, and the fields and campus of Prestonwood Christian Academy. Image courtesy of Google

Prestonwood Christian Academy also boasts seven state titles in boys basketball (including three recent years in a row) and eight in competitive cheerleading. NBA power forward Julius Randle attended Prestonwood before heading to Kentucky for a one-and-done scholarship year, and former Philadelphia Phillies catcher Cameron Rupp is also a Prestonwood Academy grad. Prestonwood likes winners.

When I got there for Saturday night worship, I found out that Prestonwood had a big Fourth of July celebration planned for Independence Day. Pastor Jack Graham promised at the beginning of Saturday worship that they’d be “celebrating our freedoms as a country … and singing patriotic songs,” as well as offering a pastor dunk tank, games and refreshments in the Dallas summer heat.

When I walked in, I noticed that the arena-style worship space that seats 7,000 had been covered with red, white and blue American flag bunting. Flags festooned the stage, and most of the screen designs and backgrounds were red, white, and blue.

As Graham concluded his welcome for the evening service, he said, “We’re going to start with the Pledge of Allegiance, the national anthem and honoring our service members.”

I had not said the Pledge of Allegiance since elementary school, and I could not help but think of the Ten Commandments — ostensibly as influential here as the pledge. The First Commandment, as found in the Book of Exodus, warns against worshipping and pledging allegiance to a flag and not to God, but no one around me seemed to mind, so, feeling a compulsion to conform, I put my hand on my heart and mouthed the words.

We then sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” and sat as the songs for each branch of the armed forces played, and veterans and active-duty soldiers were invited to stand when their branch was called, and we applauded.

American flag. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

In their faces, I saw the faces of so many veterans I had met while working as a chaplain at the VA hospital in Minneapolis. I knew that not all would call themselves heroes, that not all were proud or grateful for their service. I also knew that most were grateful to be recognized, carrying the weight of a country’s wars in their own fragile bodies and carrying too the wounds of those conflicts in their bodies, their minds and their hearts.

Pastor Graham came forward next, introducing that weekend’s theme: “America, Israel and the Road to the Future.”

Prestonwood had decided that in order to sanctify its American patriotism and its embrace of President Trump’s America First foreign policy, the preacher would make the Bible fit a narrative of American exceptionalism (not unlike American Mormons’ suggestion nearly 200 years earlier, that the 12 tribes of Israel had an American connection).

The Rev. Jack Graham of Prestonwood Baptist Church. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

The idea of American exceptionalism having a biblical justification is not new, but Prestonwood made it fresh. The church had bright and compelling red, white and blue graphics with retro black-and-white photography, a guest preacher who specializes in travel to the Middle East, and even a special song. The video montage and song came next, followed by the guest speaker. But first, Graham had to play a little American politics. Again, he forced the Christian narrative into its Trumpian box.

“Oh, I almost forgot,” Graham said casually. “Children’s shelters at the border. We’ve been speaking almost daily with our friends at the White House … who are working to reunite children with their parents. … Irrespective of all our problems with immigration and all the chaos, it’s the call of Jesus to help hurting people.”

America had been reeling for days about the stories of thousands of immigrant children forcibly separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border; two young children being held in detention had died. Most of them were traveling dangerous journeys from crime-ridden, poverty-stricken Central American countries such as Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

America was abuzz with questions. Had the most generous nation on earth lost its heart?

Yet at Prestonwood, all was good. In fact, Trump’s daughter Ivanka earlier that week had donated $50,000 to Prestonwood’s efforts to “care for children at the border.” Her donation represented an especially cunning twist, as was Graham’s statement that the White House was “working to reunite children and families,” when in fact American government officials had separated children from their families in the first place.

Graham, I noticed, euphemistically referred to “children’s shelters,” as opposed to what these centers had been called for years: detention centers. If you want to control the narrative, control the language. Graham did that masterfully, coming across as compassionate, conservative and patriotic. He insinuated that America was taking care of migrant kids, despite all the problems on the border. Yes, you could feel good about that. All those recordings of children crying, the devastated families: fake news.

In this June 17, 2018, photo provided by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, people who were taken into custody related to cases of illegal entry into the United States, sit in one of the cages at a facility in McAllen, Texas. (U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Rio Grande Valley Sector via AP)

Just as quickly, Graham turned the congregation’s attention to the video screens. The images were stirring. First, cameras panned to the Iwo Jima Memorial in Washington, then service members saying goodbye to their children before being deployed, followed by Marines holding back tears at a military funeral.

The song playing in the background, written by Prestonwood’s musicians, was equally patriotic and tear-jerking. The chorus rose, repeating that we would never forget their sacrifice, never forget the way they lived and the way they died. The greatest love on earth was to serve and die in the American military, the song suggested.

It’s a good song. Even hearing it months later, I could sing it and fill in the words. Watching the video, I thought of my dad’s dad, who fought in the Pacific in World War II, was shot in the stomach and nearly died. He was airlifted to Australia and lived the rest of his life with war wounds, internal and external. I thought of my father-in-law, a brave farm kid from rural Missouri drafted into the Army and flown to Vietnam in 1968, just in time for the most tumultuous year in American history. My heart swelled with pride, and I nearly cried.

At the end of the song, I looked around, and nearly everyone in the massive sanctuary was standing in rapt attention, staring lovingly at the flags on the stage and applauding feverishly.

This time, I stayed seated, still thinking about the First Commandment. My love for my country and my love for my God warred within me.

Angela Denker is a Lutheran pastor and veteran journalist. This article is adapted with permission from “Red State Christians: Understanding the Voters Who Elected Donald Trump,” to be published in August from Fortress Press.