Earthrise is a photograph of the Earth and parts of the Moon’s surface taken from lunar orbit by astronaut Bill Anders in 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission. Photo by Bill Anders/NASA/Creative Commons

But seven months earlier, the astronauts aboard NASA’s first manned mission to orbit the moon, Apollo 8, were at a loss for words.

In December 1968, James Lovell, Frank Borman and Bill Anders prepared to become the first humans to journey beyond Earth’s orbit, circling around the dark side of the moon. Just about everyone on the planet would be listening.

What could they possibly say as they watched that pale blue dot rise over the moon’s horizon on Christmas Eve?

“We wanted to do something significant, not so much religious as to give them sort of a shock in the psychological solar plexus, to help them remember Apollo 8 and humankind’s first venture from the earth,” Anders later told PBS.

Before their mission, the astronauts had contacted a government public affairs specialist named Joseph Laitin for his advice, according to a 2018 Boston Globe report.

It was Laitin’s wife, Christine, who reportedly suggested the trio read the creation account from Genesis 1, the foundation of a number of world religions.

The passage begins with the words, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.”

Borman read last, ending the transmission with a holiday greeting.

“And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you — all of you on the good Earth,” he said.

Atheist activist Madalyn Murray O’Hair later sued the U.S. government, alleging the Genesis reading was a violation of the separation of church and state. Her case was ultimately dismissed.

But the crew members of Apollo 8 weren’t the last space travelers to bring religion with them into orbit. From NASA’s Apollo missions to SpaceIL’s recent moonshot, and from Christmas to Ramadan, humans have found ways to practice their beliefs while touching the heavens.

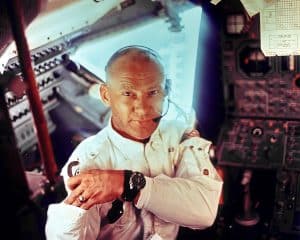

This interior view of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module shows Astronaut Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, Jr., during the lunar landing mission. Photo by Neil A. Armstrong/NASA/Creative Commons

Not long after that Christmas Eve, astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin became the first person to celebrate the Christian rite of Communion in space in the moments before he and Armstrong touched down on the surface of the moon 50 years ago this Saturday (July 20).

Several others have since. Three Catholic astronauts received Communion aboard the space shuttle Endeavour in 1994, astronaut Tom Jones recalled in his memoir. So did astronaut Mike Hopkins aboard the International Space Station in 2013, according to Catholic News Service.

“When you see the Earth from that vantage point and see all the natural beauty that exists, it’s hard not to sit there and realize there has to be a higher power that has made this,” Hopkins told Catholic News Service.

Religious rituals in space aren’t confined to Christianity, either.

The first Israeli astronaut, Ilan Ramon, had written the Kiddush, the Jewish blessing for wine, into his diary so he could offer it aboard the space shuttle Columbia “during his space Sabbath which he read over the radio to Earth,” according to Wired.

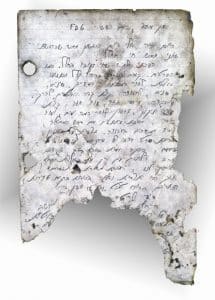

A page from the diary of Ilan Ramon with the Friday night Kiddush blessing. Photo courtesy of The Israel Museum

Ramon, whose father had fled Nazi Germany and whose mother had survived the concentration camp at Auschwitz, was killed when Columbia disintegrated upon reentry in 2003, minutes before it was expected to land at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Only about 40% of the space shuttle and its contents has ever been recovered.

Ramon’s is the only diary that was found, wet and crumpled in a field outside Palestine, Texas. Scientists and scholars spent four years restoring its pages before it was displayed in 2008 at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem — his handwritten Kiddush clearly readable on its pages.

His wife, Rona, told Wired it was “a small miracle that needs to be shared.”

Ramon also had carried a drawing of the Earth from the perspective of the moon by a Jewish boy killed at Auschwitz and a small Torah that had been smuggled into the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

The first known Ramadan prayers offered from orbit came from Malaysia’s first astronaut, Sheikh Muszaphar Shukor, aboard the International Space Station in 2007.

Shukor, an orthopedic surgeon selected as a crew member on the station’s 16th mission, would be in space during the tail end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Though the Muslim Shukor was intent on observing the associated rituals, fasting and praying while in space wasn’t a straightforward endeavor.

The ISS orbits the Earth at around 17,500 mph (making it difficult to pray in the direction of Mecca, especially while floating in microgravity) and completes one revolution roughly every 90 minutes, meaning the sun rises and sets far more frequently than for stationary humans below. This makes it unclear when to break one’s daily Ramadan fast, which begins at sunrise and ends at nightfall.

To address these concerns, Malaysia’s space agency convened 150 Islamic scientists and scholars, who ultimately produced a document outlining instructions for observing various rituals while in orbit, usually by establishing a list of preferred options “based on what is possible.”

For example, the authors concluded that if it is too difficult to pray toward the Kaaba, the building at the center of the Great Mosque of Mecca, it would be permissible to simply pray toward Earth.

The document was ultimately approved by Malaysia’s National Fatwa Council, and Shukor brought into space Malaysian satay — skewers of spicy meat — and cookies to give to others aboard the space station to celebrate Eid al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan.

Beyond the rituals of the major faiths, tokens of religious devotion also have been part of many space flights.

St. Seraphim of Sarov, one of the Russian Orthodox Church’s most revered saints, was an 18th-century monk known for his hermetic lifestyle, visions of the Virgin Mary and reported ability to perform miraculous healings.

He’s also known for his 2017 spaceflight.

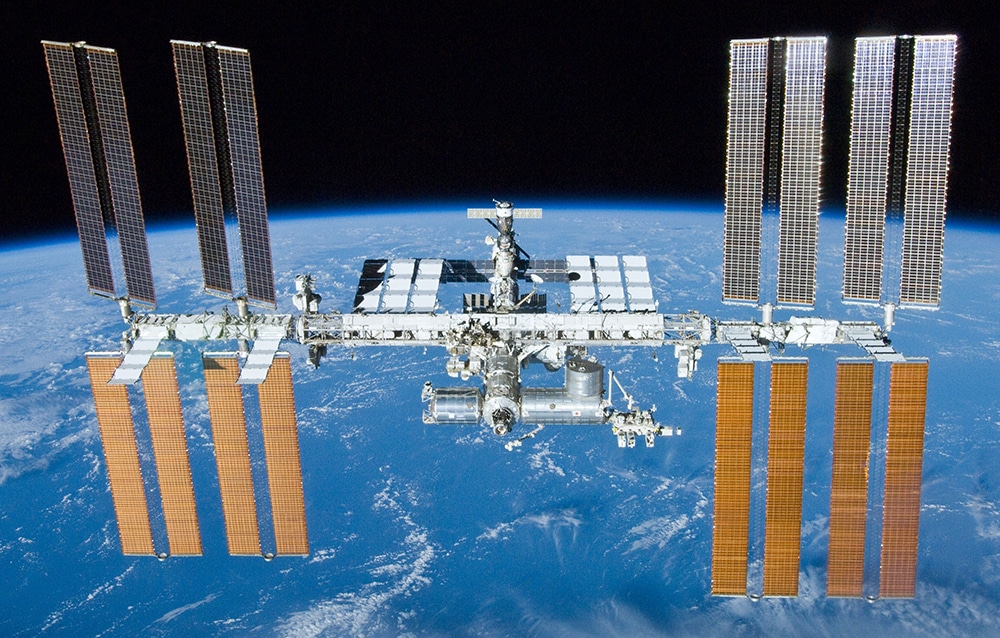

The International Space Station as viewed from the Space Shuttle Atlantis on May 23, 2010. Photo by NASA/Creative Commons

Russian cosmonaut Sergei Ryzhikov carried a relic of the saint with him — a gift from a monastery — to the International Space Station, according to The Associated Press.

“We always wait for some sort of miracle, but the fact that a piece of the relics traveled to the orbit and blesses everything onboard and outside, including our planet, is a big miracle in itself,” Ryzhikov told The Associated Press.

Russian space travelers have taken relics of at least six Orthodox saints and a piece of the Holy Cross with them, according to The Associated Press. Roman Catholic astronauts have carried with them crucifixes, prayer cards, icons and religious items and other mementos from schools, parishes and friends, according to Catholic News Service reports.

Earlier this year, an Israeli moonshot went back to the beginning.

When the Israeli group SpaceIL began working with American aerospace company SpaceX to plan the launch of SpaceIL’s scrappy unmanned lunar lander, they quickly ran into an unexpected religious problem. SpaceIL planned on hitching a ride on a SpaceX rocket to get the project into space, but the U.S. company normally launches its rockets on Saturdays — traditionally a day of rest and religious observance for many on SpaceIL’s staff, some of whom are Orthodox Jews.

A selfie taken by the Beresheet moon lander spacecraft while roughly 23,350 miles from Earth. Image courtesy of SpaceIL

SpaceIL and SpaceX eventually agreed to a Thursday launch, and the Israeli group’s Beresheet lander — whose name is a reference to the Hebrew word for “in the beginning” in Genesis — took its trip to the moon, carrying, in addition to scientific instruments, a massive digital library that included religious texts. The lander also toted along a separate virtual time capsule loaded with Israeli symbols, a Bible and a copy of the Jewish Wayfarer’s Prayer.

Though the SpaceIL lander crashed into the lunar surface due to an engine glitch, the group has signed a partnership to share its technology with another U.S. company, Firefly Aerospace, which will embark on its own moonshot.

The name for Firefly’s lander?

Genesis.