Photo by Tung Wong on Unsplash

(RNS) — Messaging is incredibly important in American religion.

Phrases like, “It’s not a religion, it’s a relationship” are pervasive in evangelicalism. In fact, if one attended a Southern Baptist Church this Sunday, the only time the word “religion” would be used would almost certainly have a negative connotation.

The same is true in American politics. While the data clearly indicates that the Republican Party has moved further away from the middle of the political spectrum than Democrats have, lots of chatter on social media seems to indicate the opposite.

That chatter accuses Democrats of being out of touch with the American mainstream.

Give some credit to the Republican messaging operation — they have made the term “Democrat” synonymous with the word “socialist.”

However, messaging has consequences. If one party tries to make the other look extreme and voters internalize that message, they will perceive the political landscape as being hopelessly divided.

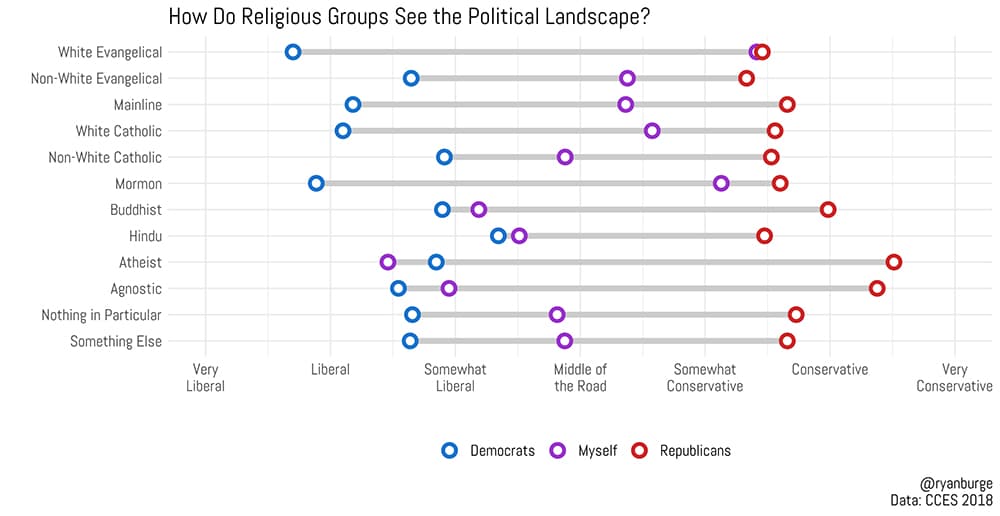

Data from the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study seems to show exactly that. The survey asked respondents to place themselves on a scale from “very liberal” to “very conservative.” They were also asked to place both the Republicans and Democrats on the same scale.

It’s a perfect test of messaging.

The survey found that most respondents placed themselves in the middle — somewhere on the spectrum between somewhat liberal and somewhat conservative.

“How Do Religious Groups See the Political Landscape?” RNS graphic by Ryan Burge

Religious groups, however, are different. White evangelicals, for example, see themselves as being just as conservative as the Republican Party. Their perceived political outlook is exactly the same as the GOP. And they see Democrats as being their polar opposite.

Non-white evangelicals, mainline Protestants, and white Catholics see themselves as closer to the Republicans than the Democrats, as do Mormons.

The nones — those who claim no religious affiliation — on the other hand, see themselves as having the same political beliefs as Democrats. Atheists, who are a subset of the nones, see themselves as more liberal than the Democratic Party.

One last thing jumps out: No religious group seems really caught in the middle. American religion has sorted itself out and taken political sides.

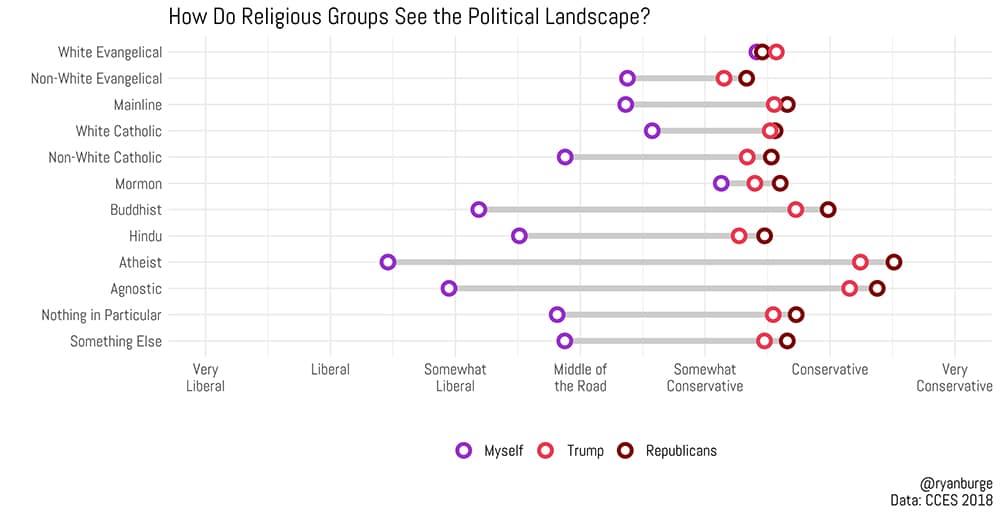

But where do Americans see Donald Trump?

The data indicates that most religious groups see Trump as being less conservative than the Republicans.

“How Do Religious Groups See the Political Landscape?” Graphic by Ryan Burge

However, one exception is white evangelicals. They see essentially no daylight between themselves and our current president. And, despite the fact that only about half of Mormons voted for Donald Trump in 2016, they are the group that is the second closest to his perceived political position.

But it’s also noteworthy that many moderate political groups like mainline Protestants see themselves as closer to Donald Trump politically than the GOP.

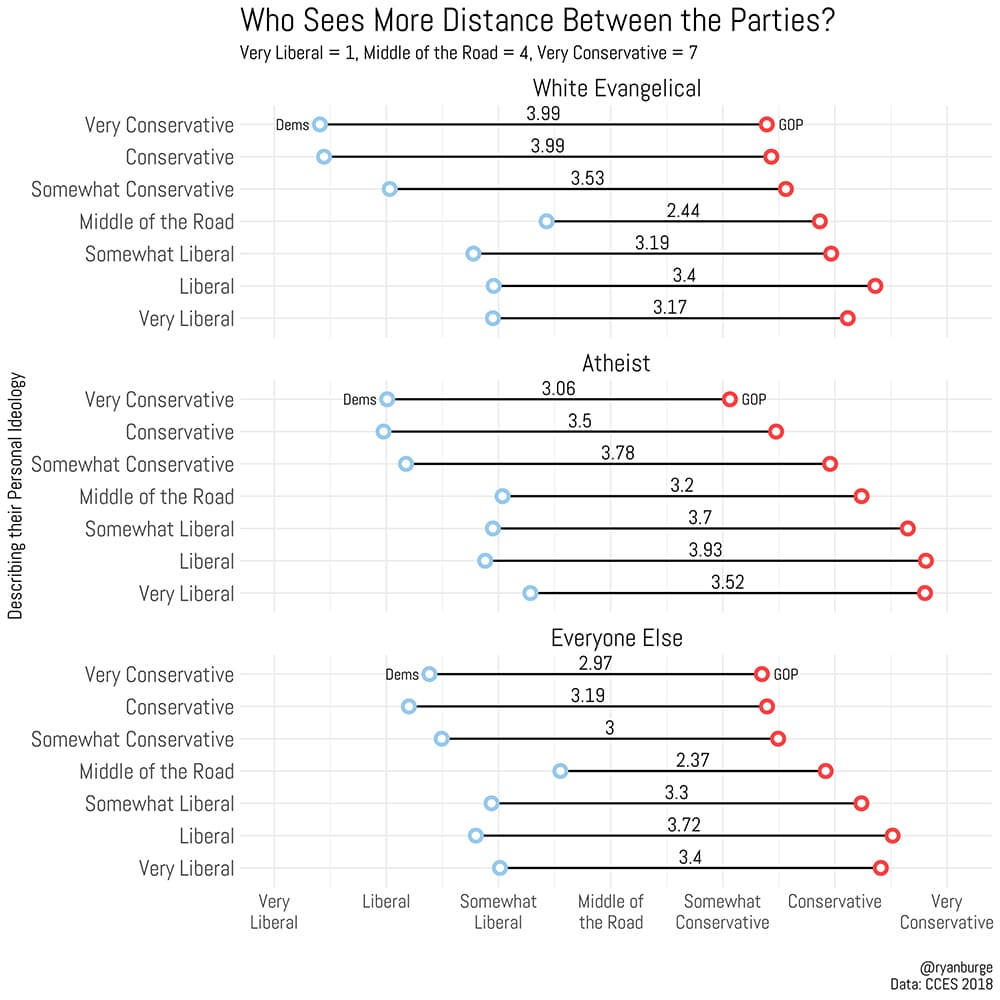

In looking at the data, I wanted to answer a central question: If someone labels themself personally as at the edge of the political spectrum (i.e. very conservative or very liberal) are they more likely to place the opposing party in an extreme political position?

I chose the two religious groups that are, on average, the most conservative (white evangelicals) and the most liberal (atheists). I calculated where a very conservative white evangelical placed the Republicans and the Democrats, as well as a conservative white evangelical and even an evangelical who described themself as “middle of the road.” Then I did the same for atheists, as well as the entire sample, for a good comparison case.

Because the scale I used runs from very liberal (1) to very conservative (7), the largest possible gap between the ratings of each party is six points.

The first finding from this data that jumps out to me is that conservative white evangelicals see a huge distance between the parties — four points.

“Who Sees More Distance Between the Parties?” RNS graphic by Ryan Burge

That’s for two reasons: They place the Democrats further to the left than any other religious group, but they also put the GOP in a fairly moderate position. Essentially, they see the other party as fringy but see their favored party as just slightly to the right.

This same pattern is apparent among atheists, as well. Liberal atheists actually see the GOP as a more extreme political party than white evangelicals do the Democrats. Yet atheists consistently place Democrats closer to the “somewhat liberal” category — which means that the overall distance between the estimates is consistently smaller than it is for white evangelicals.

Here’s the story: White evangelicals think that the Republican Party is more moderate than any other religious group. And because their personal ideology is very similar to the GOP’s, white evangelicals also see Democrats as the lunatic fringe.

Liberal atheists see the Democrats as being fairly centrist, while believing that the GOP is also a fringe party.

Both groups sum up the political landscape this way: “My party is moderate and sensible, while the other party is filled with extremists.”

I suspect this is fueled in part by the social media echo chamber. A Facebook feed that continually tells a conservative white evangelical about how states like New York and Illinois have passed laws making infanticide legal is bound to make readers think that the Democrats have moved far to the left.

In the same way, a liberal atheist’s social feed about multiple states passing so-called “heartbeat bills” is going to make that religious group see the Republican Party as just as extreme.

The result is this: Strong partisans see their party as reasonable and the other as very much out of step with the mainstream. This vilification of the other side poisons both the political and religious wells. Compromise becomes impossible when an elected official is told by his constituents to not engage with “the nut jobs on the other side.”

But, a pastor is going to have a hard time winning converts to their congregation when those on the outside think that evangelical churches are filled with far-right extremists who blindly follow the dictates of Donald Trump and the Republican Party.

What we are left with are tightly bunched groups of Americans, sorted based on political and/or religious views that are seemingly light-years away from any other group. Occasionally they stick their heads up only to point out the absolute worst in the other tribe, which causes their group to huddle together even more tightly.

It seems like a lifetime ago when then-presidential candidate John McCain was asked at a town hall rally about President Obama being a Muslim and an Arab by a woman in the crowd.

McCain responded with grace, saying, “He’s a decent family man, a citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign is all about.”

I worry that there are more people like that woman in churches and at campaign rallies every year and that the person being asked those questions is going to double-down on the divisive rhetoric instead of trying to tamp down the vitriol.

Recently I have been thinking quite a bit about the theological term “Imago Dei,” which is pervasive in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It’s the belief that every human being is born in the image and likeness of God and is worthy of respect. We would create a better future by looking for the Imago Dei in each other, instead of finding excuses to create “us vs. them.”

(Ryan Burge teaches political science at Eastern Illinois University and is a co-founder of Religion in Public. He is also an American Baptist pastor.)