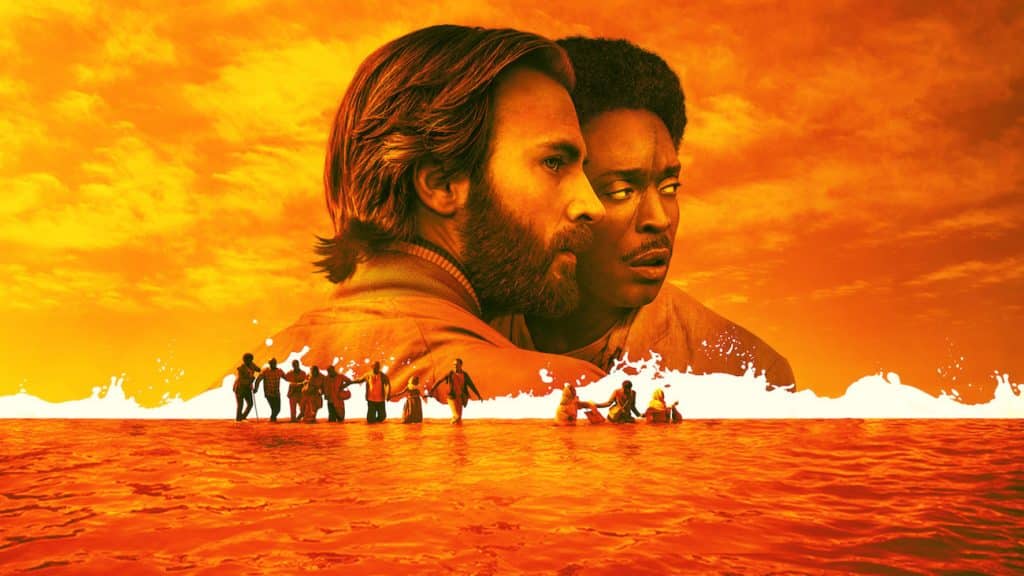

Film poster for “The Red Sea Diving Resort,” starring Chris Evans and Michael K. Williams. Image courtesy of Netflix

(RNS) — There is no glamor to Sharon Shalom’s memories of his evacuation from the Sudanese desert to Israel 35 years ago.

“I had to leave my parents behind in Sudan,” said Shalom, now a rabbi in Tel Aviv, in a phone interview. “The Mossad came in the middle of the night to take us on the trucks. In one small truck, we had 150 people; the mission was very dangerous.”

Now the daredevil operation by Israel’s secret service to rescue more than 8,000 Ethiopian Jews from Sudanese refugee camps in the early 1980s has become “The Red Sea Diving Resort,” a fast-paced Netflix drama that turns Chris Evans, best known for playing Captain America, into a dashing Israeli hero.

Rabbi Sharon Shalom. Video screengrab

If the Hollywood gloss makes the mission out to be “Ocean’s Eleven” in the Nubian Desert, Shalom, who advised the filmmakers on the events of the rescue, said he’s glad nonetheless to see a little-known journey of faith dramatized for a global audience.

“Some friends here in Israel will argue it doesn’t reflect the exact accurate story,” he said. “The bottom line is, it helps us not to forget what happened, and it starts a conversation.”

The resort of the film’s title refers to the dilapidated holiday retreat that the Mossad purchased as a cover for what they dubbed Operation Brothers. “They had to pass as non-Israeli to help run this fake hotel,” said the movie’s writer and director, Gideon Raff, whose pilot for “Homeland,” Showtime’s espionage series starring Claire Danes, won him a share of two Emmy awards for screenwriting in 2012.

“These were people who had international backgrounds and grew up in other places,” Raff said.

This explains in part why Evans, as the taciturn team leader Ari Levinson, heads a cast that includes British stage actor Alex Hassell and the Ukrainian-accented Mark Ivanir, with the dandified Ben Kingsley as Levinson’s Mossad superior, Ethan Levin.

After Levinson convinces Levin to let him round up his band of unlikely familiars, the disguised agents take up residence at the resort, only to find themselves serving actual tourists who have come for vacation. As their guests sleep, they ferry the Ethiopians in nondescript trucks to Mossad agents waiting in small boats up the coast, who transfer the refugees onto a larger vessel and safety.

The film’s portrayal of the team’s derring-do, shot in South Africa and Namibia, was a test of Director of Photography Roberto Schaefer’s lighting skills. “These operations were always on the darkest Friday of the month, when the moon is really just a sliver,” said Raff. “How do you light a whole desert?”

Actors Michael K. Williams, left, and Chris Evans in “The Red Sea Diving Resort.” Photo courtesy of Netflix/Marcos Cruz

Michael K. Williams (“The Wire”) plays an Ethiopian community leader who serves as the conduit between the Mossad and the refugees, an amalgamation of several covert contacts in the Sudanese camps. Chris Chalk (“Gotham”) plays the villainous Sudanese Colonel Ahmed who tries to frustrate the Israeli plan.

Authenticity was paramount for the filmmakers, who at one point hired a Ugandan C-130 Hercules transport plane actually used in several other refugee rescue missions.

Raff began work on the film by seeking out those who participated in Operation Brothers, and not only the Mossad agents who pulled off the ruse. “I spent a lot of time with the Ethiopians who courageously left their homes and crossed the desert,” he said.

Gideon Raff participates in the “Tyrant” panel at the FX Winter TCA Press Tour, on Tuesday, January 14, 2014 at the Langham Huntington, in Pasadena, Calif. (Photo by Phil McCarten/Invision for FOX/AP Images)

One of those was Shalom, who told Raff his story firsthand as the script was being developed and helped him locate other former refugees.

“It is amazing how Israeli soldiers and Mossad agents answered our letters,” said Shalom, which he said is a testimony to the bonds formed during the high-risk operation. “Suddenly they met brown tribes in Sudan country, we who are Ethiopian Jews. These commandos trained in how to kill people embraced us and began to cry. This happened — and we really are brothers.”

Though the film focuses on the Israeli effort to get them out, it is the Ethiopian Jews, Raff said, who made history in Operation Brothers. “Ethiopian Jews started this whole thing,” he said. “They left their homes and marched to Sudan. They wrote letters to every Jewish organization hoping to arrive in Jerusalem, their homeland. Sometimes they don’t get enough credit for how they were proactive in their rescue and smuggle into Israel.”

Shalom, whose Ethiopian name was Zaude Tesfay, remembers the trauma. “We walked from our village in Ethiopia, a dangerous journey by foot. A lot of people died on the way. But our forefathers teach us: ‘Go, keep going, and never stop.’ So we never gave up.”

The rich history of Jews in Ethiopia begins as far back as 950 B.C.E., during the reign of King Solomon. Other historians date their heritage to the first century.

“We didn’t come to be Jewish in one day,” said Shalom, who wrote a history of his people in “From Sinai To Ethiopia” in 2016. “The Ethiopian Jews are descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Without our power, faith, hope and dreams, this mission would never have happened.”

Edward L. Johnson, a pastor in Lincolnville, South Carolina, and author of “These Were God’s People,” a chronicle of the Ethiopian Jews and other African diaspora groups, said via email, “Africa is the most ethnically diverse continent on the planet. It is when you research these groups that you are then able to see their differences in beliefs, culture, and religion. The biggest mistake that Europeans made when they began to conquer Africa is when they lumped all Africans into one basket as ‘black people.’”

The drama of the Ethiopians’ deliverance into Israel was followed by the longer, sometimes harder, journey of assimilation.

Renamed by Israeli authorities after his arrival at age nine, Shalom served as an officer in the Israeli Defense Forces before attending rabbinical school and became one of the first Ethiopian-Israelis to be ordained by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

Still, he has seen his people face marginalization in society. “When we came, they told us we are not 100% Jewish,” said Shalom. “They say, ‘You do not look like Jews.’ A lot of people felt inferior about their identity.”

This January, Shalom saw a lifelong dream come true when he was appointed founding chair of The International Center for the Study of Ethiopian Jewry established at Ono Academic College near Tel Aviv. It is the first such center globally to document the journey of Ethiopian Jews.

“We want to tell the true story of Ethiopian Jews, and want people to understand it,” said Shalom. “This center will explain and describe Ethiopian Jewry — not from a paternalism that seeks to devalue us, but from reality.

“The center helps next-generation Ethiopian Jews feel that they belong here in Israeli society.”

Chris Evans, left, and cast in “The Red Sea Diving Resort.” Photo courtesy of Netflix

At a time when Israel is increasingly the target of criticism internationally for its hardline approach to peace negotiations, the film’s Israeli heroes may not be entirely well received.

“Sure, people will criticize the fact that this story happens to be about Israel,” said Raff. “But this is not a political movie; it’s a human movie. This story about people coming together — of former refugees helping refugees — is very timely.”

The film concludes by noting the current refugee crisis, with over 70 million displaced people globally. Raff said he and his team hope it spurs viewers to action.

Shalom believes the movie could offer hope precisely to those caught up in the ongoing strife in his part of the world.

“With all the conflict here in the Middle East, I see a lot of hate and fear of others,” he said. “This movie is important for all human beings — not simply Israelis and Ethiopians — because it’s a unifying story of brotherhood.”