Photo by Pexels/Creative Commons

(RNS) — Most of us have a vague idea that there is a significant need for foster parents. As someone familiar with the abortion wars, I’m reminded of the fact often: Rarely does a week go by without someone making some version of the argument that we need abortion rights because of deep problems with America’s foster care system.

But even those who are vaguely aware don’t know how badly the situation has deteriorated in recent years. As the number of children in need of homes has risen, in at least half of U.S. states the number of parents who choose to foster is actually falling.

The situation has become critical in part because of the opioid crisis. In 2000, some 15% of the 270,000 removals of children from their homes were prompted by drugs being used in the household. By 2017 that percentage had reached a whopping 36%.

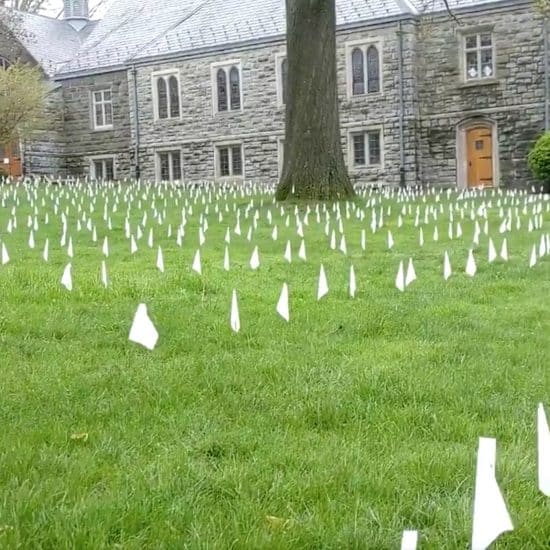

More than 100,000 kids are currently waiting for foster homes in this country, while another 20,000 will age out of the system this year. What awaits those who age out is very often not a happy situation. Data provided by the National Foster Youth Institute suggests that 20% will be instantly homeless, 1 out of 2 will develop substance dependence, just 3% will go to college (out of 70% who say they want to go), 25% will suffer direct effects from PTSD, and just half will be employed by age of 24. A disproportionately high percentage will be incarcerated.

Some states and nonprofits have been trying new things to sign up potential foster parents. Yard signs, church booths, and billboards still exist, but there’s increased focus on targeted digital ads, brand management and even community discount cards (to use at local businesses) for those who choose to foster.

But even if they can be recruited, prospective parents often get disillusioned early in the process. Agencies are stretched thin and overworked. Initial calls are often not returned for weeks, or even months. Those who do agree to foster face the frightening possibility that a child they have grown close to will leave.

Though there are also incredible joys associated with foster parenting, most Christian organizations now mobilizing to meet the growing need are quite direct about the fact that it can also break your heart.

This is especially true as fostering agencies and support groups reorient toward seeing the best outcome as reunifying kids with their families.

For years, charitable organizations like Project 1.27, named for the chapter and verse in the New Testament’s Letter of James commanding Christians to give special concern to orphans, have talked about reunification as “the dark side” of what they were offering foster parents.

Lately, groups have shifted their message. “We need to step into the messiness — often generational messiness — of these families and show Christ’s love,” Project 1.27’s president, Shelly Radic, told the Gospel Coalition last year.

“The first goal of foster care is always reunification of a family,” said my colleague and friend Holly Taylor Coolman, a veteran foster parent who is Roman Catholic and chairs the department of theology at Providence College. “That’s pro-life in an exponential way. Functioning, stable families are the absolutely indispensable life-giving context.”

Responding to the dignity of the human person is precisely this kind of self-gift, with no thought of ownership or control over the outcome.

This is a new way of approaching fostering that fits into the broader Catholic ethic of life. OneLife LA, a pro-life initiative founded by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, is focused on celebrating the “beauty and dignity of every human life from conception to natural death.”

This Sunday (Oct. 13), OneLife LA is sponsoring Catholics Love Foster, an event at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles that is billed as an appreciation of foster parents. The event also aims to recruit large numbers of new foster families.

On the one hand, OneLife LA simply is continuing an already robust Catholic commitment to foster care (including efforts organized by the U.S. Catholic bishops to find foster homes for refugees, undocumented immigrants and victims of trafficking). But in other ways this approach is a completely new tack to inspire and recruit foster parents.

Perhaps as importantly, OneLife LA is concerned with raising awareness about other ways people can be of service in the foster crisis.

Among many excellent ideas, OneLife LA suggests bringing meals to foster families, mentoring foster kids, driving foster kids to church and even becoming an official court-appointed special advocate for a child.

The shortfall in meeting the needs of foster children is a crisis. We need all hands on deck, even if we disagree with some of the views of particular agencies. This is something to which all Christians are called: God has explicitly commanded us to have special concern for the orphan. Especially now, with the need so great in the U.S., we have no excuse for not stepping up to the plate.