Devotees light earthen lamps on the banks of the River Sarayu as part of Diwali celebrations in Ayodhya, India, on Nov. 6, 2018. The north Indian city of Ayodhya attempted to break the Guinness World Record for most lit earthen lamps on the banks of river Saryu on the occasion of Diwali – the festival of light. (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh)

(RNS) — With more than a billion people celebrating Diwali, which comes this year on Oct. 27, the festival is one of the largest and most significant religious observances around the world. But the occasion carries different meanings for different religious communities.

In fact, Diwali has various interpretations even among the world’s various Hindu communities. Some Hindus recognize it as the day represented in the classic Hindu epic, Ramayana, when the protagonists, Rama and Sita, arrive in Ayodhya after 14 years of exile; Diwali is often celebrated as the day of their return. In the south of India, many Hindus mark Diwali as the day Krishna defeated the demon Narakasura and thereby freed the 16,000 girls in his captivity. In western India, many Hindu and Jain communities consider Diwali as the first day of the new year.

In Nepal, the occasion is called Tihar (not Diwali) and focuses on the worship of the goddess Lakshmi. Tihar follows after Navratri (or Dussehra, which they call “Dasain” in Nepali), a celebration of the goddess Durga/Kali/Camunda, among other things. Some Hindus also celebrate the occasion as the day Naciketas (of the Katha Upanishad) returns from his conversation with Yama (Death), bringing the secret of moksha (spiritual liberation) back to the world. According to this tradition, no longer would one’s life end just in a heaven or the underworld – now there was a whole new end to aim for.

People light lamps at the Banganga pond as they celebrate the Hindu Dev Diwali festival in Mumbai, India, on Nov. 22, 2018. (AP Photo/Rajanish Kakade)

Liberation is a common theme for other religious traditions that celebrate different occasions on this same day.

In the Jain tradition, Diwali marks the day that Mahavira – the last Jain spiritual leader (tirthankara) – attained physical death and final enlightenment in the sixth century BCE. Jains refer to this day as Mahavira Nirvana Divas (the day of Mahavira’s liberation), and Jain traditions announce that the community has been celebrating this occasion since the event of Mahavira’s final nirvana over 2,500 years ago.

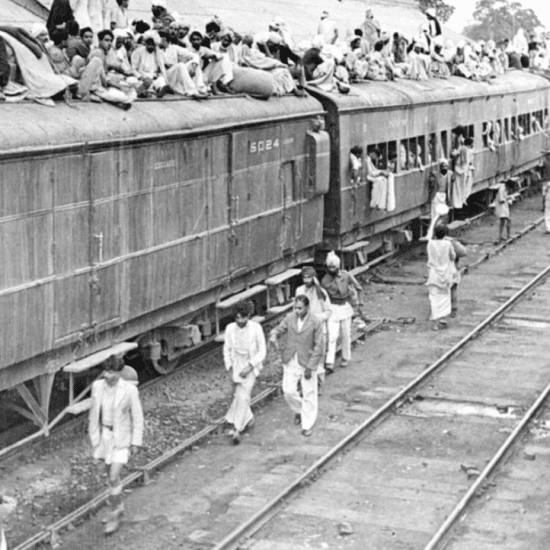

On this same day, Sikhs commemorate Guru Hargobind’s return to Amritsar after being unjustly imprisoned in Gwalior for several years. The sixth guru refused to be released without also securing the release of 52 other Hindu kings who were unfairly incarcerated with him. To this day, nearly 400 years later, Sikhs refer to this occasion as Bandi Chor Divas (The Day of Liberation).

I have always loved that liberation on this day can both be political and spiritual, depending on which tradition we’re talking about.

Because these celebrations occur on the same date, many have wrongly assumed Diwali to be a Pan-Indian festival that transcends religion, mistakenly thinking it’s a celebration that must have the same meaning for everyone with a few cultural differences.

In this Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018, file photo, a woman colors earthen lamps ahead of Diwali festival in Jammu, India. People buy these lamps to decorate their homes during the annual Hindu festival of lights. (AP Photo/Channi Anand, File)

Perhaps a better way to understand Diwali is through its distinctive meanings, histories and even names for various religious communities. It is true that Diwali has become a cultural holiday for many South Asians regardless of their particular religious backgrounds. Given that Hindus make up the vast majority of India’s population, it is the Hindu versions of Diwali that have come to dominate the popularized cultural form of the occasion.

At the same time, Sikhs and Jains have retained their own ways of marking the occasion in ways that honor their distinctive stories and commitments.

A helpful analog might be the way Christmas has become simultaneously a Christian holiday and also one that is broadly cultural and transcends religious identity. It’s not unheard of for Jews or those of other faiths to have a Christmas tree in the house in December, without necessarily investing in the birth and life of Jesus Christ and while retaining their own cultural and religious traditions.

It is true too that, in addition to the shared date, the distinctive occasions celebrated on Diwali all celebrate the triumph of righteousness, often represented by light. For many Hindus, light symbolizes Rama’s righteous defeat of the evil king Ravana, and for many Jains, light symbolizes Lord Mahavira’s spiritual liberation (nirvana). More broadly, the traditional lighting of lamps signifies how light vanquishes darkness.

A Hindu boy holds sparklers to celebrate the Hindu new year holiday of Diwali. Photo courtesy Creative Commons.

This Diwali, I am particularly drawn toward two accounts that overlap with pressing issues in our world today: the story of Krishna freeing thousands of girls imprisoned by evil Narakasura, and the account of Guru Hargobind delaying his own release while insisting on the release of others who were also wrongly imprisoned.

As we sit here and look at the world burning all around us today, I am reminded that these stories are not just mythical legends or historical accounts. They are models that help us envision what true righteousness looks like. They are sharp rejoinders of what we should be doing and how we should be living.

These stories feel especially meaningful today as we witness the wrongful detainment and unjust imprisonment of so many communities. What would Krishna do if he saw young children imprisoned by a heartless government at the U.S.-Mexico border? Or Uighur Muslims detained in concentration camps across China?

How would Guru Hargobind respond if he witnessed the wrongful criminalization and mass incarceration of young black men? Or the creation and subsistence of our school-to-prison-pipeline? Or the privatization of America’s prison industrial complex?

These are the kinds of questions that I am pondering as we commemorate Diwali, Mahavira Nirvana Divas and Bandi Chor Divas this year. If we want to honor these memories and the lessons we draw from them, wouldn’t we seek to apply these ideals into our own lives and situations?

There are plentiful parallels of injustice and wrongful imprisonment in our world today for us to consider; pick yours. This is the season for us to contemplate the models Diwali gives us for what it means to embody liberation, justice and the triumph of righteousness.