Mysterious people with political connections arrived from a country off in the East. They brought news the ruler did not like. There was a new claim to the throne. An effort was underway to remove him and install another ruler. King Herod wanted to dismiss the claims as “fake news” and a “hoax” — not because the intelligence report was inaccurate, but simply because he didn’t like the news. These Magi, after all, had done their research.

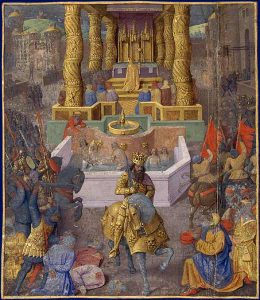

The taking of Jerusalem by Herod the Great 37 BCE, by Jean Fouquet – Public Domain

The arrival of foreign individuals with news of an overthrow effort — a “coup,” he wanted to call it — shook Herod. Although he liked to pretend the people loved him, even making up high poll numbers just to feel loved, he knew deep down the truth behind his constant lies. He liked to call himself “Herod the Great,” but realized that few outside his palace staff did so.

He sat on the throne only because of the interference of a foreign government. And he remained in power because he won the approval of a foreign dictator, Augustus. But Herod knew that Augustus could easily orchestrate Herod’s downfall through an assassination order or merely by withdrawing support and embarrassing Herod. So, news from a different foreign power in the East — one seemingly at odds with his own foreign benefactor — greatly troubled Herod.

“Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews?” those “nasty” Magi had asked. “We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.”

Herod christened himself as “the chosen one.” Then came these “really, really bad” ones with information that another might actually be chosen. Perhaps he could give them belittling nicknames to undermine their credibility. Lyin’ Balthasar, Little Melchior, and Low-Energy Casper. But that might not do the trick. Herod knew he need to take decisive action to stop “the squad” and their “very fake news.”

How could this happen to him? It wasn’t fair, Herod insisted. He had built a “beautiful” wall at the Temple to keep out of the holy area those Gentiles who were “rapists” (including some, he assumed, that were probably “good people”). Did he need to add a moat to keep people happy? And he had built big “beautiful” buildings with golden features. Why couldn’t people realize only a great person could build big things? Sure, he had greatly enhanced his own wealth, profiting off his time in government. But couldn’t the people see that he was going to make Israel great again? They had a temple now. Clearly that was better than the last guy, even if it meant moving toward a system with a more autocratic ruler.

After being disturbed by the news from the “dopey” Magi, Herod called together his exegetical advisory council. Perhaps these religious leaders could help him out. They always seemed to pacify a large swath of the people that otherwise would surely be dismissive of a man who had divorced his wife to remarry, abandoned his child, enjoyed decadent entertainment, ignored the religious traditions, and even profaned the holy Temple. So, he asked his religious advisors where this “witch hunt” originated.

“In Bethlehem in Judea,” they answered.

He found it hard that a chosen one could come from that “sleepy” town. But his paranoia quickly kicked in. He sent the “corrupt” Magi on their way after trying to extract a quid pro quo from them so he could take out a political rival.

His trusted court priests stayed with him. Not a single one joined the search for the Messiah, all choosing to stay in the royal palace with Herod. It pleased Herod that at least these religious leaders would remain faithful to him, with a few of them even denouncing those who opposed him as “demonic.”

He soon realized, however, that his efforts to extort those “low ratings” Magi from the East had failed, so he needed to take action himself. He was, after all, a man of action unencumbered by traditional diplomatic norms. He believed anyone challenging him should be executed for treason. In his delusions he had even killed his favorite wife and some of his sons. He definitely wasn’t going to let some “do nothing” baby from some “failing” town challenge his authority.

So, in his madness, he ordered the execution of all the baby boys in Bethlehem. He didn’t care if he had to permanently separate children from their parents. If backing war crimes is what it took to stay in power, he would do it. And his religious council — or is it “counsel”? “Consul”? — stayed faithfully by his side, without a care for those Rachels weeping for their children.

Even that, however, did not ease Herod’s paranoia or depression. It was not too long before he would die, still unloved. And that new King would return from his time as a refugee to offer a new moral ethic far different from that preached by powerful rulers and court preachers. Yet, even among those claiming to support that new King, the ways of the old Herod still found support.

Perhaps he was their true king, after all.