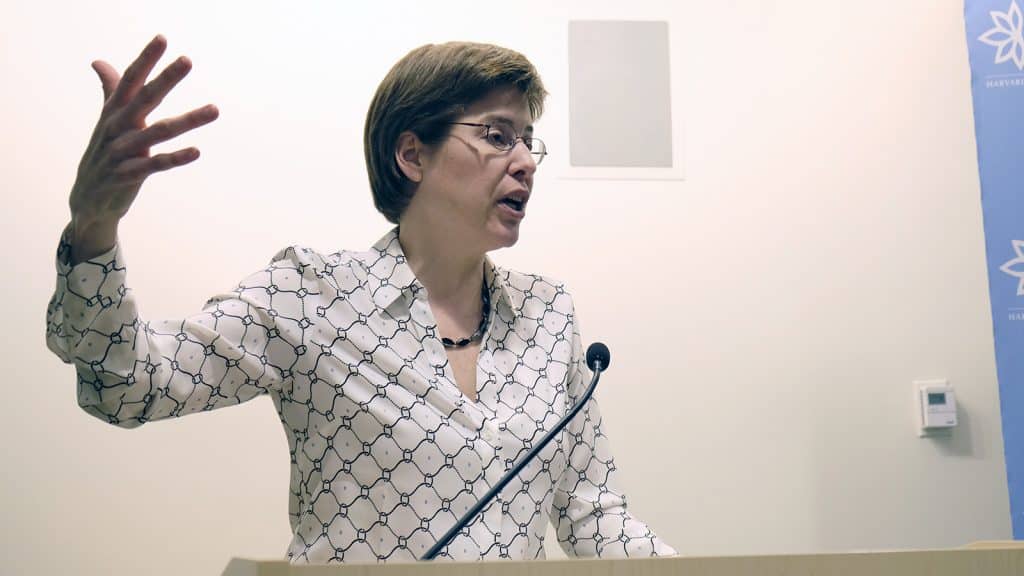

Melissa Rogers. Courtesy photo

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (RNS) — Melissa Rogers knows the laws governing the relationship between the U.S. government and religion are far from perfect.

But she’s fond of a certain quote by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: “Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?”

Prompted by what Rogers sees as a new push toward rewriting these boundaries, continued mischaracterization and distortion of church-state laws, and historic levels of hostility to religious minorities, her new book, “Faith in American Public Life,” defines the relationship between the U.S. government and religion as one with “meaningful independence,” but the ability to cooperate to do good.

As a church-state lawyer who previously served as special assistant to President Barack Obama and executive director of the White House Office of Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships, Rogers offers ways forward to preserve and refine those principles in the face of growing threats.

“We hear that the Supreme Court has kicked religion out of the public square,” she said. “We hear that a president can’t speak about his or her personal faith. We hear that our public schools should be religion-free zones. None of those things is true … and it gives rise to so many unnecessary disputes.”

“Faith In American Public Life” by Melissa Rogers. Courtesy image

Now a visiting professor at the Wake Forest University School of Divinity, Rogers spoke to Religion News Service ahead of her panel at Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of World Religions last month.

“Attacks on houses of worship or on individuals seem to happen with alarming frequency, to the degree that some Americans feel they can’t practice their faith without fear,” she said. “I view that as a crisis. … We don’t have religious liberty in America if people don’t feel they can wear some kind of religious item, a headscarf or turban or yarmulke, and walk down the street and not be afraid.”

The FBI’s newly released report on hate crimes in 2018, which is widely considered to be a serious undercount of hate crimes around the country, found that bias-motivated violence has risen to a 16-year high. Religious-based hate crimes comprised nearly 1 in 5 single-bias incidents.

Americans must “move from the sidelines of this issue into solidarity with the people who are being targeted” and hold elected leaders accountable for “fear-mongering” based on race, religion and ethnicity, Rogers said.

“When we have leaders using dehumanizing language, talking about people in groups in a way that is discriminatory and debasing, when they traffic in anti-religious tropes, when they use violent imagery and language — that can have the effect of setting off people who are on the edge — who are not mentally stable — and causing them to carry out heinous attacks where lives are lost,” she said.

Partisanship is another critical threat to the role of religion in America’s public square, Rogers said.

While noting that political labels “rarely map well on religion,” Rogers said she has seen a tendency in the media and society at large to overlook religious practices and religious liberty claims that come from the political left and center, and in turn, a tendency to overemphasize religious liberty claims that come from the political right.

“We have people practicing their faith every day in ways that that don’t fit into a conservative cookie-cutter approach,” she said. “We have Native Americans who are protesting the passage of oil pipelines across their land. Catholic nuns brought a lawsuit about that recently, in addition to issues raised around Standing Rock and other free-exercise claims made by Native Americans.”

Rogers reeled off a handful of others examples: an Arizona humanitarian worker who successfully invoked the Religious Freedom Restoration Act when he was put on trial for providing aid to migrants on the border; a South Texas Catholic diocese protesting the federal government’s efforts to use land on which a historic chapel sits for a border wall; houses of worship participating in the multifaith sanctuary movement to protect immigrants facing deportation; faith-based groups working with the government to serve as refugee resettlement agencies; resistance to the military draft; Sikhs and Muslims pushing for the right to wear headscarves, turbans and beards while serving in the military.

Melissa Rogers speaks at Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of World Religions in Nov. 2019. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Indeed, a report by Columbia Law School’s Law, Rights and Religion Project last month detailed religious liberty advocacy by progressive movements, rebutting what it called “widespread misconceptions” that only conservative Christians defend the right to religious liberty.

“It’s very important to understand that all of this activity exists out there,” Rogers said. “Free-exercise claims are often made by people who would not define themselves as politically conservative. It’s inaccurate to say the only people who take their religion seriously are people who are political conservatives.”

That’s critical to help legislators, judges and society to consider free-exercise claims more thoughtfully, Rogers said. Instead, media and policymakers often dismiss such religious freedom cases as political acts, rather than ones rooted in sincere faith.

“When you have a free-exercise claim that lines up with your policy preferences, that’s one thing,” she said. “When you have a free-exercise claim that does not line up and in fact contradicts your policy preferences, then that tests the kind of analysis you will do. We should be consistent when we evaluate free-exercise claims and dignify them with a fair and neutral hearing.”

Rogers suggested that objective bipartisan standards should also be afforded to the Trump administration’s controversial appointment of televangelist Paula White as a part-time adviser to the White House Faith and Opportunity Initiative.

Rogers has previously criticized White’s continued promotion of religion-themed products while in office, writing that appointees selling items “accompanied by promises of spiritual rewards … will rightly be viewed as a manipulative scheme that shamefully has the imprimatur of the United States government.” That, she said, was one of several basic standards that administrations from both parties have upheld in their previous faith-based partnerships.

Still, she said, those critical of White’s appointment should remember the Supreme Court has ruled that fencing clergy members out of public office is unconstitutional.

“I certainly think we should not, whether it’s a Democratic or Republican administration, take the position that simply because someone is a minister that they cannot serve in public office,” she cautioned.

But the White House’s unofficial evangelical advisory council, which White has helped spearhead, does raise potential transparency issues for Rogers. Under the Obama administration, officials publicly released logs of White House visitors, a practice the Trump administration has eschewed. She emphasized that the White House must ensure it remains in line with Federal Advisory Committee Act regulations that mandate public records of policy recommendations made by commissions.

Rogers said she is also deeply concerned by appearances of favoring certain religious communities in the White House faith-based partnerships today.

“There can’t be a complacency about just having members of one religious tradition, or indeed a subset of a subset of a religious tradition, included in meetings at the White House,” she said. “There has to be a very broad discipline of reaching out to people of all faiths. And it’s not clear to me that that has been happening the way that it should be.”