On Tuesday (April 14), U.S. President Donald Trump announced the U.S. would halt funding to the World Health Organization despite the global role of the WHO in fighting the coronavirus pandemic. Trump’s move echoes political fights decades ago as the son of a Danish Baptist preacher transformed the health arm of the United Nations to adopt a social justice approach to health across the world.

As of April 15, more than 2 million people globally have been infected with the COVID-19 respiratory disease caused by coronavirus, and more than 134,000 have died. More than 30 percent of the cases and more than 20 percent of the deaths are in the U.S., which has more than 640,000 infected persons with more than 28,000 dead.

The Trump administration has faced increasing criticism — from health officials and governors of both parties — for its handling of the health crisis. The slow response, low testing rate, and rhetoric downplaying the virus’s seriousness may explain why the U.S. is experiencing a worse outbreak. For instance, South Korea found its first case of coronavirus on the same day as the U.S., but now has fewer than 11,000 cases and 225 deaths.

President Donald Trump speaks about coronavirus and the WHO in the Rose Garden of the White House on April 14. (Alex Brandon/Associated Press)

Trump now tries to shift the blame to the WHO by claiming they had overly praised China’s response and didn’t take the coronavirus seriously, even though Trump previously tweeted praise for China’s “transparency” with coronavirus in January before WHO experts were even allowed by the Chinese government to visit to investigate the outbreak. Additionally, as the WHO warned about coronavirus in late February, Trump called the warnings about the virus a “new hoax” from Democrats.

Trump’s funding freeze of the WHO echoes rhetoric by another U.S. president who sought to lower the U.S.’s support as a Danish Baptist preacher’s son led the global health effort.

Born in Vivild, Denmark, in 1923, Halfdan Mahler started a career in medicine that ultimately led to him serving for 15 years as the third director-general of the WHO. At first, he considered following his father, Magnus, into Baptist ministry as the younger Mahler started preaching at age 15. However, he instead studied medicine.

After leading a Red Cross anti-tuberculosis effort in Ecuador, he joined the three-year-old WHO in 1951 as a senior officer in India working on the Tuberculosis Programme. In 1962 he moved to the WHO Headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, to serve as chief of the Tuberculosis Unit. Eventually, he became director-general in 1973.

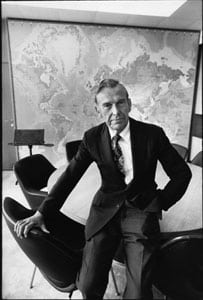

Halfdan Mahler. (Erling Mandelmann)

Three years into role leading the WHO, Mahler delivered a speech calling for “health for all by 2000,” which led to the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata to establish his vision as a global priority. This approach, which Mahler pushed with missionary zeal inherited from his father, called for a focus beyond just establishing various programs to combat a single disease to instead work on strengthening whole health systems in countries.

Mahler explained in a 2008 interview that he led the “search for a balance between the vertical (single disease) programmes and the horizontal (health systems) approach” because “you can’t have one approach without the other, they go hand in hand.” With this, he insisted health should be defined, as the Declaration of Alma-Ata states, as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

“Primary health care will not succeed unless we can generate participation from individuals, families, and communities, but this community participation will not work unless there is support from the health system,” he explained. “For most, it was a true revolution in thinking. Health for all is a value system with primary health care as the strategic component. The two go together.”

“Our goal was to focus world attention on health inequities and on trying to attain an acceptable level of health, equitably distributed throughout the world,” he added.

He said he saw this as part of “social justice.” This approach to health included pushing environmental health concerns like clean drinking water and sanitary waste disposal, as well as calling for systemic changes to what criticized as “neo-colonialism in health.”

“Unless we all become partisans in renewed local and global battles for social and economic equity in the spirit of distributive justice, we shall indeed betray the future of our children and grandchildren,” Mahler declared in a speech in 2008 as he reflected on his work as WHO head. “When people are mere pawns in an economic and profit growth game, that game is mostly lost for the underprivileged.”

“Are you ready to address yourselves seriously to the existing gap between the health ‘haves’ and the health ‘have-nots’ and to adopt concrete measures to reduce it?” he added as he challenged a new generation of global health leaders. “Are you ready to fight the political and technical battles required to overcome any social and economic obstacles and professional resistance to the universal introduction of primary health care?”

And Mahler knew what it meant to fight political battles to implement his “health for all” vision. Some in the U.S. attacked the WHO under Mahler for what they saw as a “political” and “anti-capitalist” approach, criticizing the focus on global inequities and WHO efforts to challenge practices by multinational corporations deemed harmful to public health. For instance, under then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan, the U.S. cast the sole vote against the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes crafted by Mahler’s WHO after Nestlé aggressively pushed products in underdeveloped countries that undermined infants’ health. Reagan also froze contributions to the WHO’s budget, and later paid only a fraction of the U.S.’s regular contributions to the WHO and other UN agencies.

As Mahler lamented after leaving the WHO, he felt the “political pressures” from some governments took energy away from “genuine health issues” the WHO sought to address. And four decades later, the political criticism of the WHO continues.

The White House’s statement on the decision to halt funding not only repeated Trump’s claims about the coronavirus response, but added, “The United States seeks to refocus the WHO on fulfilling its core missions of preparedness, response, and stakeholder coordination.” That vision would seem to align with the pre-Mahler WHO approach of dealing just with disease outbreaks instead of holistic health systems.

With the U.S. as the largest donor to the WHO — giving about 15 percent of the WHO’s budget — the move could undercut the WHO’s programs around the world to fight not just coronavirus but also polio and measles, as well as provide humanitarian health and nutrition in conflict zones like Syria and address other health concerns in underdeveloped communities. Leaders across the globe denounced Trump’s move, and the American Medical Association said that to cut funding “during the worst public health crisis in a century” is “a dangerous step in the wrong direction.”

Although Mahler died in 2016, his legacy in transforming the WHO into a holistic health focus that included social justice matters continues to this day. As do the political fights about his “health for all” vision.