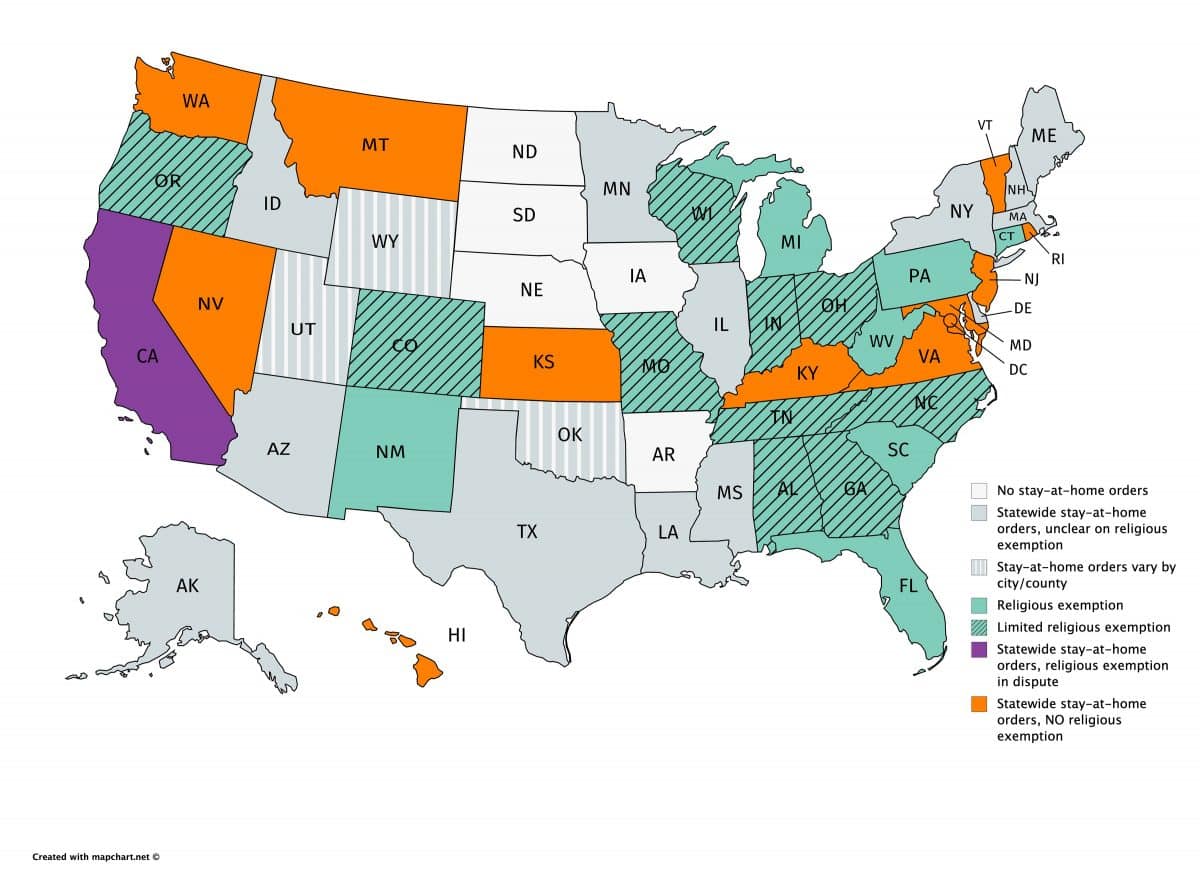

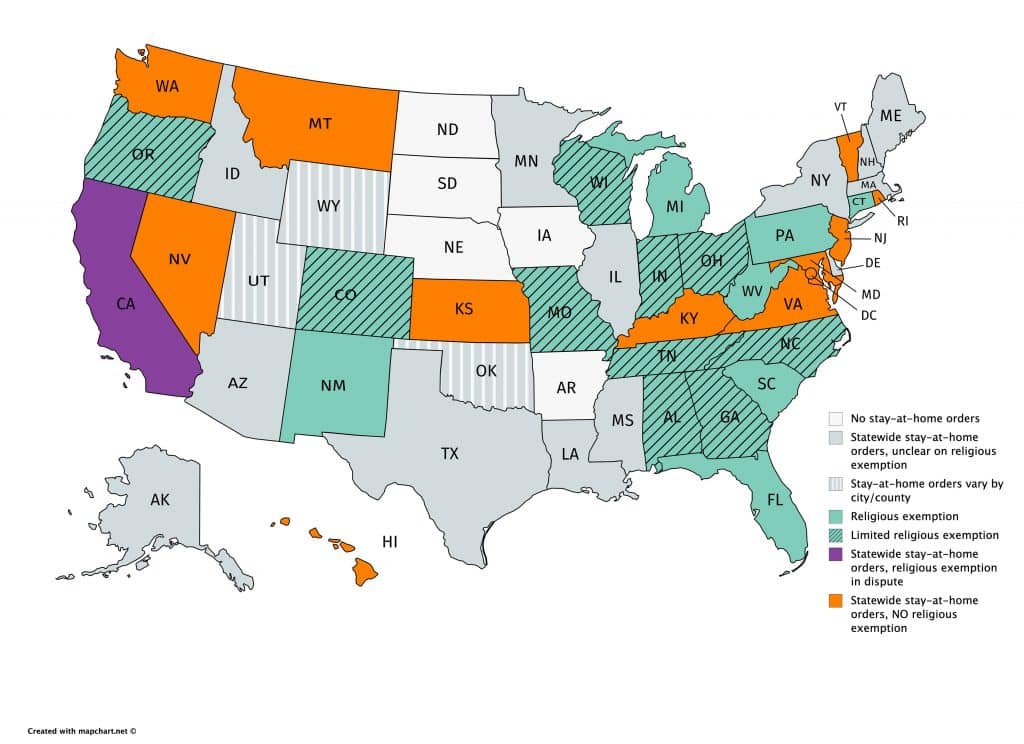

United States map of religious exemption to stay-at-home orders due to the coronavirus. Updated April 14, 2020.

(RNS) — The coronavirus pandemic has raised a number of difficult questions concerning personal freedoms and public safety, with religion front and center. Should congregations continue to gather in person for worship and other social functions? Can the state restrict religious organizations from fully free functioning?

In recent cases in Louisiana and Florida, these issues have come to hinge on a pastor’s will to defy government orders, making the question less philosophical than empirical. My colleagues Ryan Burge, Andrew Lewis and I conducted a survey of 3,100 American adults from March 23-27, asking a number of questions about their own and their congregation’s reactions to the spread of the coronavirus. (While not a randomized sample, we used Census-based quotas to construct a sample that has the same age, gender and regional spread as American adults.)

With Religion News Service’s recent publication of a map detailing where bans on religious gatherings are in effect, we can attach our survey to try to estimate the extent of this important public dilemma.

For ease of analysis, I collapsed the RNS categories. In my charts, “No Orders” refers to the 30 states with no stay-at-home restrictions and to states where stay-at-home orders come with religious exemptions — for instance, the Dakotas as well as Michigan and Pennsylvania. “Partial restrictions” refers to the 10 states with stay-at-home orders that do not fully restrict religious gatherings (such as Ohio and Oregon).

Finally, “Religious Gatherings Restricted” covers those nine states (plus the District of Columbia) that do not exempt religious gatherings from their stay-at-home orders. Given the recent Kansas court ruling in favor of the governor’s blanket order, I counted Kansas as having no religious exemption.

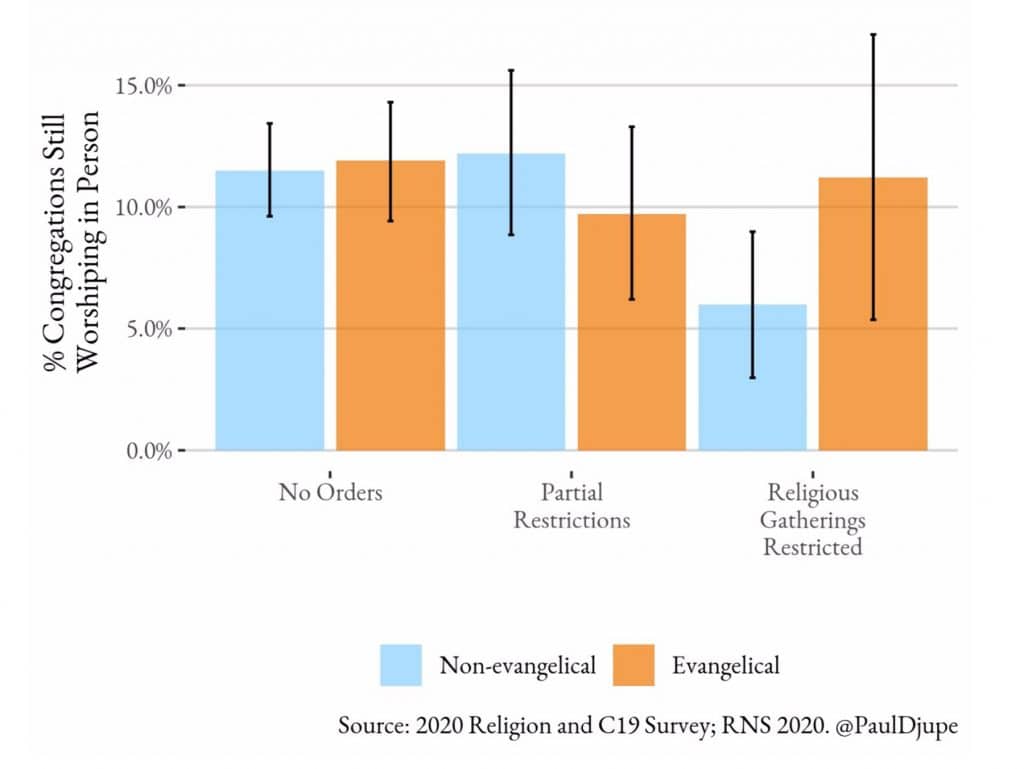

“Percentage of congregations still worshipping in person” Graphic by Paul Djupe

It is important to emphasize that only 12% of respondents reported that their congregations were open to in-person worship at the time of the survey. That figure does not vary much, except where there is no exemption for religious gatherings. In these states, only 6% of mainline Christians report their congregations are open for in-person worship, versus 12% of evangelicals.

Just because 88% of congregations are following public health officials’ advice does not mean that individuals are following suit. Our survey asked if the survey respondent was still worshipping in person even if their own congregation was closed, presumably crowding into a church that is open. This number was much higher — 20% of church attenders reported still attending in-person services. Did it vary by state regulations?

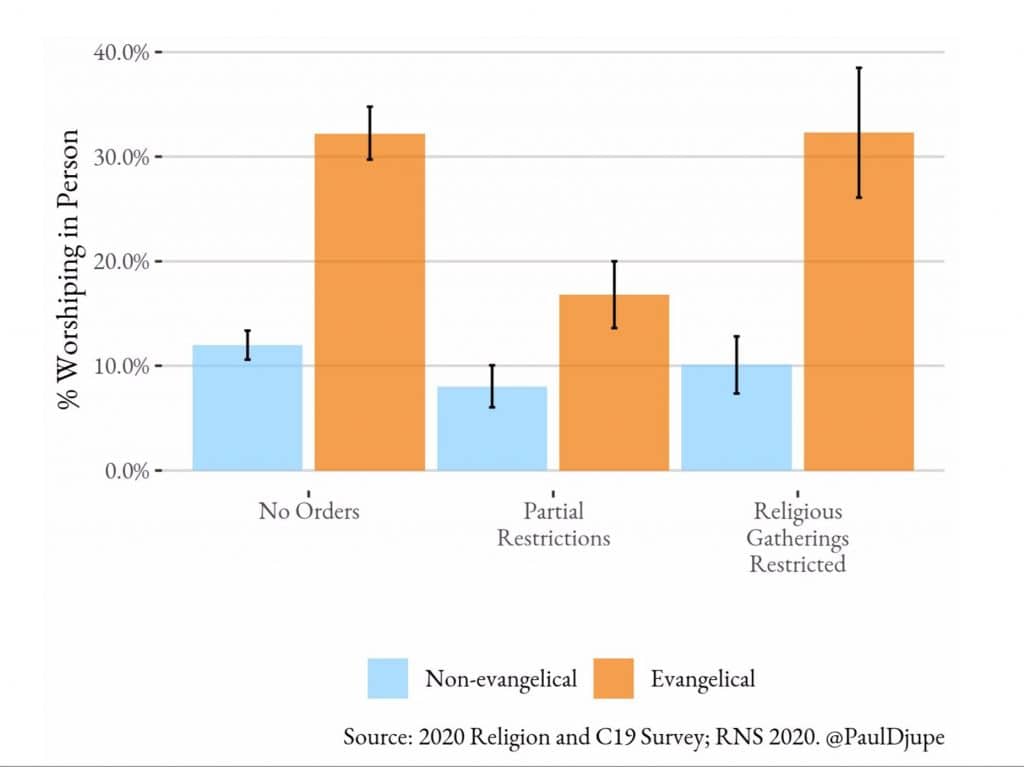

“Percentage worshipping in person” Graphic by Paul Djupe

This number varied according to state regulations, but again, evangelicals were more likely to report worshipping in person in states with no restrictions as well as states with religious restrictions. In both cases, almost a third of church-attending evangelicals reported attending worship in person. In states with only some religious restrictions, far fewer evangelicals report in-person worship — only 16%. Evangelicals’ behavior stands in contrast with non-evangelicals, among whom only about 10% report worshipping in person and without much variation across levels of state restrictions.

This suggests that evangelicals were more liable to defy both social and official expectations about staying home, a notion that was bolstered when we asked respondents if they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “If the government tells us to stop gathering in person for worship I would want my congregation to defy the order.”

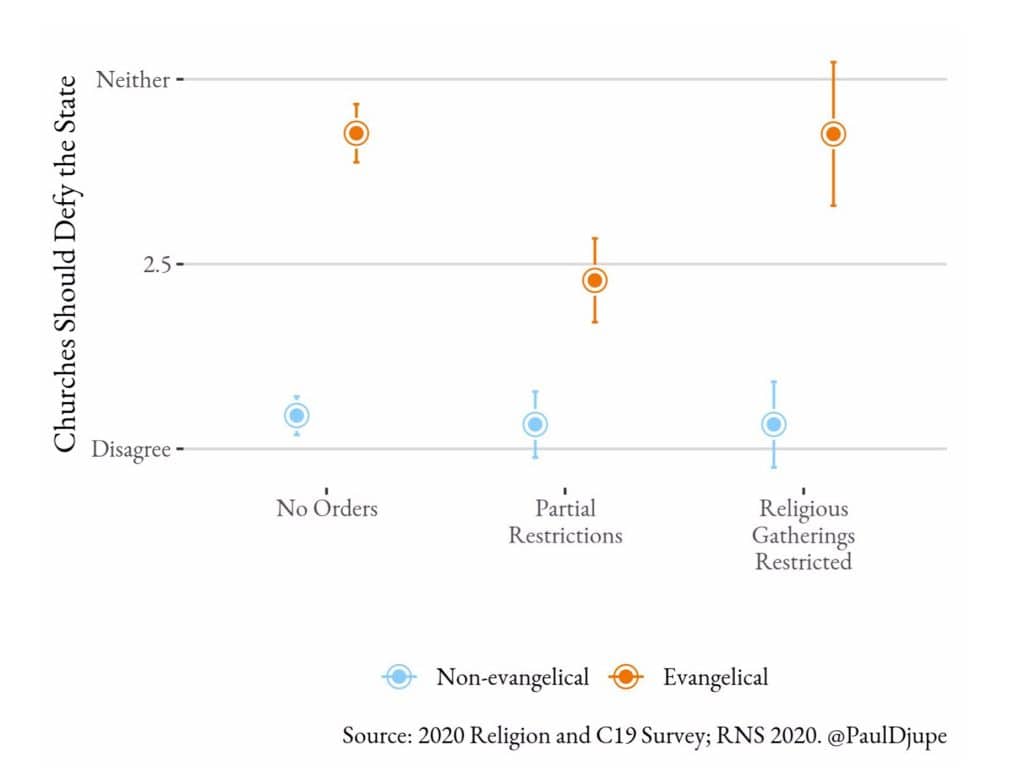

“Churches should defy the state” Graphic by Paul Djupe

What we found is that defiance is higher by some 13% among those with congregations still open and is considerably higher, by 40%, among those still worshipping in person. In the figure below, I assess how this attitude is linked to state restrictions. The pattern should look familiar. Non-evangelicals reject an attitude of defiance to state orders regardless of state restrictions. However, evangelicals take a traditional embattled stance.

On balance they do not support defiance (the average is close to “neither agree nor disagree”), but defiance is much higher when the state has no restrictions and when religious gatherings are prohibited by the state. It is just under half a scale point lower (about 10% lower) when the state has partial restrictions in place. In all cases, though, evangelicals are much more supportive of defiance of the government than non-evangelicals.

On balance they do not support defiance (the average is close to “neither agree nor disagree”), but defiance is much higher when the state has no restrictions and when religious gatherings are prohibited by the state. It is just under half a scale point lower (about 10% lower) when the state has partial restrictions in place. In all cases, though, evangelicals are much more supportive of defiance of the government than non-evangelicals.

Evangelicals have been preparing for this moment. In a 1998 book, sociologist Christian Smith famously referred to evangelicals as “embattled and thriving,” and we can see that embattled mentality on display here. But this view is also currently being stoked by religious elites, with a number of evangelical leaders calling for active resistance against state orders. Christian right legal groups such as Liberty Counsel are spoiling for fights; other Christian right think tanks are urging resistance, supporting the few individual clergy who are quite open about their mission.

The Rev. Tony Spell, the Louisiana pastor who has been charged with a misdemeanor for keeping his church open, told Reuters: “The church is the last force resisting the Antichrist. Let us assemble regardless of what anyone says.”

The sad fact is that a few of the dissident churchmen have now contracted, and at least one has died of, COVID-19. It appears that only through viral infection do holdout congregants finally get the (public health) message.