People protest stay-at-home orders at the state Capitol in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on April 20, 2020. Video screengrab via Twitter/Miguel Marquez

(RNS) — As the nation debates ending widespread lockdowns in hope of saving the economy, even at the risk of losing more lives to COVID-19, some religious organizations are leading the reopen charge. The Christian legal group Liberty Counsel has already branded May 3 as #ReOpenChurchSunday.

Faith, many behind this movement allege, is the ultimate protection. The evangelical activist David Barton recently described the course he would have national leaders take during this crisis: “What you do is call for days of prayer and fasting. If we can get a hold of God on this and get God to intervene then we can see an end to this.”

A photograph taken at an anti-shutdown rally in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, captured this confusion of public health and personal devotion succinctly: One protester had painted the hood of his truck with the motto “Jesus is my vaccine.”

The stubborn popularity of this notion goes back to a similar conflict between the guidance of medical experts and hope in divine intervention almost exactly 300 years ago. The “Jesus is my vaccine” crowd lost the fight then, and the most prominent Christian clergyman in America delivered the decisive blow.

In 1721, Massachusetts was in the grip of one of the periodic smallpox epidemics that had ravaged New England for decades. Half of Boston showed symptoms. Mortality in the city approached 10%. Similar to our day, this was seen by many as not just a health crisis, but a theological one. The majority of the population regarded the epidemic as divine will.

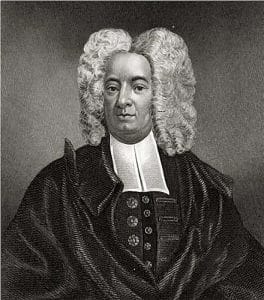

Cotton Mather portrait, circa 1700, by artist Peter Pelham. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

To a Puritan clergyman like Cotton Mather, the most important Colonial preacher and thinker of his day, the cause of any catastrophe was usually clear enough. Years before, when he heard of an earthquake that destroyed the city of Port Royal in Jamaica, he believed the ground had shaken because the people of that colony had fallen into the heathen excitement of visiting fortunetellers. Mather likewise saw a connection between the number of miscarriages in Boston and the “great and visible decay of piety” in the city.

Such hardships could be understood as the result of the wrath of God, and so the best recourse Christians had was to atone, much as the likes of David Barton propose now.

Yet when smallpox hit close to home, Mather began to rethink this position. With his children suddenly showing symptoms he had seen when visiting the dying in “venomous, contagious, loathsome Chambers,” as he called the houses of the afflicted, he began to wonder: If it was in humanity’s power to counteract illness through the God-given gift of the intellect, wouldn’t it be wrong to fail to do so?

Because Puritan ministers were the public intellectuals of their day, some styled themselves men of science as well as men of the cloth — Mather most of all. He was eager to prove his learning equal to that of any of his peers back in England, and so he read as many European medical texts as he could lay his hands on. Emboldened by these interests, Mather proposed a radical new treatment — inoculation — be used to fight smallpox.

But doing so meant breaking ranks with both his country’s religious elite and what then passed for common sense: If plagues were sent by God, to work against them was blasphemy.

The controversy that followed was both the first conflict between science and religion in America and the first media-addled public health disaster. Printer James Franklin (Benjamin’s brother) fanned the flames by publishing screeds against inoculation generally and Mather personally.

Many of the attacks on Mather focused on the source of his information. While also known as a witch hunter who had helped build the case against the accused in Salem, Mather was surprisingly broadminded about where he looked for new ideas. He had first learned of inoculation’s efficacy from Boston’s enslaved population, who had received the treatment before being kidnapped, sold and brought to America.

Specifically, he heard of inoculation from a man named Onesimus, who was enslaved by Mather himself. Long before he came across the procedure in his European medical texts, Mather wrote, “I had from a servant of my own an account of its being practised in Africa.”

Onesimus described the practice in detail and showed him the scar it had left on his arm. After Mather learned Onesimus had been inoculated, he sought further evidence, talking to others in Boston’s enslaved community. Their accounts proved that in non-Christian lands he had thought inferior to his own, the supposedly cutting-edge practice was commonplace.

When the origin of Mather’s opinions became known, suspicion of the practice became more fervent than ever. Like current anti-shutdown efforts, opposition to inoculation was shadowed by violence. A lit grenade thrown through the minister’s window came with a note: “Mather, you dog! I’ll inoculate you with this!” Apparently the fuse fell out when it hit the floor.

When the reopen lobby includes conspicuously armed contingents demonstrating in front of statehouses, tying a note to a bomb to protest a public health initiative has a familiar ring. But the historic and present-day protests have more in common: You don’t throw an incendiary device or put on tactical gear unless you’re terrified that the way you see the world might be wrong.

These lines from a 1721 anti-inoculation pamphlet get to the heart of it: “Is it not taking God’s work out of his hands?” opponents demanded of inoculation. “Is it any better than dictating what measure of his judgement we intend to have?”

If inoculation worked, in other words, then God was not in control, and if God was not in control, many feared they would not have their greatest source of solace just when they needed it most.

It may be giving too much credit to assume those pushing to reopen the country prematurely are moved by heartfelt feelings they are unable to articulate and don’t merely want to be seen. But it’s worth remembering, particularly as #ReopenChurchSunday approaches, that “Jesus is my vaccine” is the prayer of someone motivated mainly by fear — of COVID-19 and all they don’t know.