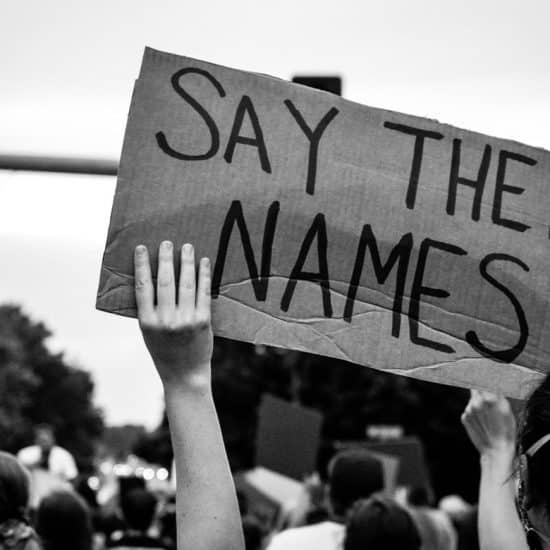

People participate in a rally May 8, 2020, in Brunswick, Georgia, to protest the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed black man. Two men have been charged with murder in the February shooting death of Arbery, whom they had pursued in a truck after spotting him running in their neighborhood. (AP Photo/John Bazemore)

(RNS) — Will your church say anything about Ahmaud Arbery this Sunday? Did your church say anything about Breonna Taylor last Sunday?

In the past few weeks, news of the tragic and dramatic deaths of these young African Americans has managed to rise above the all-consuming pandemic coverage. Arbery was killed by two white men while jogging. Taylor was killed by police in her own home.

For the past decade I’ve pastored an urban, intentionally multiracial church — “intentionally” because it’s our belief that reconciliation across lines of segregation powerfully witnesses to the reconciling gospel of Jesus. While the percentage of racially diverse churches like ours is growing, we’re still something of an anomaly on the landscape of American Christianity.

But just because multiracial churches are rare doesn’t mean they aren’t attractive. I’ve found that most Christians like the idea of diversity in their churches. I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve been told something like, “I’d love to be a part of a diverse church, but my town (suburb, neighborhood, etc.) is so white.” These people will also express their interest in racial justice while again lamenting that there’s nowhere to direct this passion in their racially homogenous setting.

These conversations reveal an assumption that, when it comes to racial reconciliation and justice, the real action must be left to churches like mine. White Christians and their majority white churches, the thinking goes, don’t have an important role to play.

The work, according to this perspective, is “over there”: in the city, within the diverse churches, among communities of color. It’s the same assumption that keeps white churches silent when, once again, black women and men are killed, and black communities traumatized.

The problem with this assumption is it incorrectly pushes racial injustice off on people of color, when race was historically constructed by whites in order to benefit whites. Though the social hierarchy of race comes at the expense of women and men of color, the work of deconstructing it must be done by those who constructed it. By assuming that white churches and ministries have nothing significant to contribute to the reconciliation of the church, we misunderstand how race works.

Photo by StockSnap/Creative Commons

Sure, the most deadly impacts of racial segregation and injustice are experienced in communities of color, at the other end of the racial hierarchy. The deaths of Arbery and Taylor are just the latest horrifying examples. Yet given the sinful origins of race, we must assume that no one in our racialized society is unscathed, least of all those of us who are white.

Not long ago I read a letter from the leaders of a white church who were troubled by a Christian organization’s emphasis on racial reconciliation. The authors ended with a question. What, they wanted to know, would this organization do to address the problem of fatherlessness in the African American community?

My heart broke reading this letter. How could this church and its leaders imagine a monolithic African American community? Who had convinced them that black fathers are somehow lesser than their white counterparts? Why could they not see the pressures faced by many African American communities and families? A massive wealth gap caused by generations of federally imposed housing discrimination, unequally funded public schools, mass incarceration fueled by racially biased policing and prosecution, communities targeted for shady mortgages, and so on.

I also grieved that I know so many amazing black dads who thrive despite the pressures they face. I have a front row seat to many African American churches in our neighborhood that disciple men to be good fathers and call them to levels of responsibility and godly character that I’ve rarely seen in white congregations. These men and their churches understand the negative stereotypes they face and they’re doing everything possible to prove them wrong. Yet they are invisible to the authors of that letter.

But this is precisely how race affects white people: It conceals the truth from us. Rather than seeing the struggles faced by our African American family in Christ, we are prone to believe the stereotypes of our racialized society.

It reminds me of what James Baldwin wrote years ago, that white people are “still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”

We don’t have to remain trapped. By reframing race and racism from something to be engaged with “over there” to something that must be reckoned with in our own white communities and churches, we get closer to the truth of history, and to the challenges we face as the diverse body of Christ. Reframing race calls each white congregation to take its place in the ministry of reconciliation. We can no longer outsource it to churches like mine.

In these days we have seen COVID-19 devastate black and indigenous communities. Asian Americans have been targeted and scapegoated, and Wanda Cooper mourns her son Ahmaud. It is time for white Christians to reframe the way we’ve understood race. There are sins of omission and commission to confess. There is apathy and ignorance to repent of. There is solidarity with the beautifully diverse body of Christ to build.

A white church that chooses to publicly lament the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and Breona Taylor is discipling its members away from the lie that race only matters somewhere else. Likewise, a white congregation that begins listening to the stories of sisters and brothers who have recently immigrated will begin waking up to the painful realities our race has concealed from us.

By reframing race as our responsibility, white churches will find the ministry of reconciliation that was waiting for us all along.