If Joe Biden wins the November election, his running mate announced Tuesday (Aug. 11) will become the fifth Baptist vice president. However, as a Black and Asian American woman, Senator Kamala Harris of California stands in stark contrast to the other Baptist VPs — especially the first one, a slaveholder who was open about his enslaved common-law wife and their children.

Four of the nation’s 45 presidents claimed the Baptist faith: Republican Warren Harding (1921-1923), Democrat Harry Truman (1945-1953), Democrat Jimmy Carter (1977-1981), and Democrat Bill Clinton (1993-2001). And four Baptists can be found among the 48 vice presidents, including Truman who held that post for less than three months before assuming the presidency after Franklin Roosevelt died. Other Baptist VPs include Republican Nelson Rockefeller under President Gerald Ford (1974-1977) and Democrat Al Gore under Clinton (1993-2001).

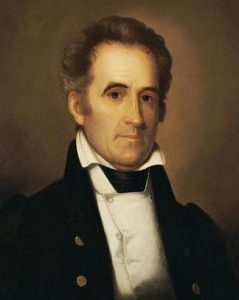

Richard M. Johnson

And then there’s the first Baptist to hold the second-highest office in the land. Richard Mentor Johnson, a Democrat who served as the nation’s ninth VP during the term of President Martin Van Buren (1837-1841).

Van Buren doesn’t seem to make the list of presidents that many Americans today can name. And even fewer know his VP. However, Johnson’s personality and lifestyle captured the attention of the nation at the time.

Born in 1780, he grew up at Great Crossing Baptist Church near Georgetown, Kentucky, a church his parents helped start. Johnson quickly moved from a legal career and Kentucky state representative to join the U.S. House of Representatives in 1807.

As a congressman, he organized soldiers for the War of 1812 — often fighting Native American allies of the British. He oversaw the burning of Potawatomi villages in Indiana. And he gained fame for supposedly killing Shawnee chief Tecumseh in the Battle of Thames in Ontario, Canada — a battle that resulted in Congress requesting President James Monroe honor Johnson with a sword.

After 12 years in the House, Johnson in 1819 started a decade stint in the U.S. Senate, and then returned to the House for another eight years after losing his Senate reelection. During his time in Congress, Johnson supported the Choctaw Academy of the Kentucky Baptist Missionary Society that sought to educate and evangelize Native Americans.

Johnson also gained attention for his defense of religious liberty in the Senate when some argued mail delivery on Sunday violated biblical teachings about the Sabbath. Johnson criticized the effort to end Sunday mail delivery as “a scheme to make this government a religious, instead of a social and political, institution.” Sunday mail delivery continued until 1912.

Recounting Johnson’s role in the Sunday mail debate, Baptist historian Bruce Gourley called Johnson a “forgotten Baptist hero” who played “a pivotal role in the struggle against a conservative Christian coalition that wished to transform America into their own image.”

Johnson sought the role as Andrew Jackson’s second VP for the 1832 election, but lost in balloting to Van Buren. Almost immediately, Johnson started angling for the VP slot four years later behind Van Buren. Johnson’s supporters cited his defense of religious liberty during the Sunday mail debate. But Johnson proved controversial and nearly cost the ticket the election. All because of his love life.

When his father died, Johnson inherited a mixed-race enslaved woman, Julia Chinn. Although they couldn’t marry because she was enslaved — and he didn’t free her — he was open about their more than two-decades-long relationship, including during his time in Congress. They had two daughters together, who both were given his surname, were not enslaved, and eventually married white men and received property from Johnson.

Johnson’s relationship with Chinn led slaveholders in Kentucky to block his Senate reelection in 1828. And his sex life became a topic of racist attacks in newspapers and political materials during the national 1836 election, three years after Chinn died in a cholera epidemic. Baptist clergy who knew him and Chinn from church and the Choctaw Academy publicly defended him. And Johnson argued he was at least honest about his relations: “Unlike Jefferson, Clay, Poindexter, and others I married my wife under the eyes of God, and apparently he has found no objections.”

Despite running on his fame for killing Tecumseh — using the slogan “Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh” — his relationship with the late Chinn hurt in 1836 as many Southern Democrats refused to back the ticket, with the ticket even losing Kentucky. While Van Buren won the presidency, all of Virginia’s electors refused to back Johnson in the electoral college so he fell a vote short of winning. Thus, for the only time in history, the U.S. Senate voted to pick the VP. Johnson’s Democratic Party backed him, and he joined Van Buren in office.

For the 1840 election, many party leaders saw Johnson as a drain on the ticket, while others still recognized him as a war hero. So, Van Buren decided to run without an official running mate — allowing each state’s electors to pick their own VP. Van Buren lost.

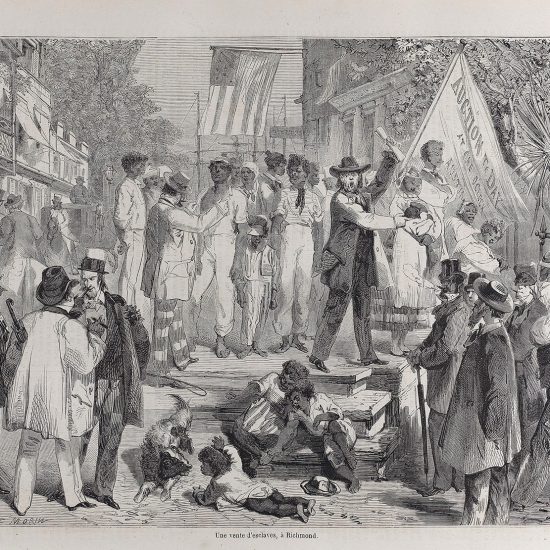

Johnson’s political career never recovered. He lost runs for the U.S. Senate, the presidency, and governor of Kentucky, before finally settling for a Kentucky House seat that he assumed just two weeks before his death at age 70 in 1850. At some point after Chinn’s death he also began an intimate relationship with another woman he enslaved. When she started a relationship with another man, he sold her at auction and hooked up with her enslaved sister.

His legacy remains as five U.S. states have a Johnson County named after him: Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, and Nebraska. But leaders in the Iowa county started talking earlier this year about perhaps changing the name to not honor a slaveholder.

Despite those county names, Johnson largely passed from American memory. Chinn did so even more. In fact, we don’t even know where she was buried.

“She’s literally been erased,” said Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, an associate professor of history and gender studies at Indiana University. “We don’t even know where she’s buried. We’ve literally lost a vice president’s wife, but because she was enslaved, no one cared.”

Come January, a new Baptist vice president might be sworn in. One who, like Johnson’s wife, is descended from both slaveholders and enslaved women.

Sen. Kamala Harris meets people before a Corinthian Baptist Church service, Aug. 11, 2019, in Des Moines, Iowa. (John Locher/Associated Press)