President Donald Trump falsely claimed in a Saturday (Aug. 22) tweet that “the Democrats took the word God out of the Pledge of Allegiance” at the Democratic National Convention. But while the DNC did include the phrase “under God” in the Pledge for each night’s session, the socialist Baptist minister who wrote the Pledge left God out of it.

In this Aug. 17, 2020 image from video, grandchildren of Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden lead the Pledge of Allegiance during the first night of the Democratic National Convention. (Democratic National Convention via AP)

Trump’s claim was based on the fact that two virtual caucus gatherings — those of the Muslim Delegates and Allies Assembly and the LGBTQ Caucus meeting — held before the main sessions included recitations of the Pledge without “under God.” However, the main session each of the four evenings used the phrase in the Pledge — including the first night when the grandchildren of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden led the Pledge. And Biden also used the phrase in his acceptance speech Thursday (Aug. 20).

“With passion and purpose, let us begin — you and I together, one nation under God — united in our love for America and united in our love for each other,” he said.

But while Biden and other Democrats said “under God,” the man who wrote the Pledge in 1892 left it out. And ‘God’ would stay out of it for another 62 years.

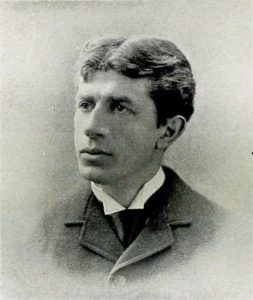

The son of a Baptist minister in New York, Francis Bellamy would follow in his father’s footsteps. The younger Bellamy attended Rochester Theological Seminary (now known as Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, which is affiliated with American Baptist Churches USA), and he pastored Baptist churches in New York and Massachusetts. He also wrote for a number of publications, including the Youth’s Companion.

For the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus reaching the Americas, the 37-year-old Bellamy wrote a salute to the U.S. flag to be used for Columbus Day celebrations. Since Youth’s Companion funded itself in part by selling American flags, pushing a patriotic salute was good business.

The Sept. 8, 1892 issue carried Bellamy’s recommended salute: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

As his words grew in use over the next few decades, the U.S. Congress officially recognized a slightly edited version in 1942: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Still no ‘God.’ Just as Bellamy wanted it.

As Baptist historian Bruce Gourley explained, Bellamy’s text “intentionally reflected the Baptist heritage of church state separation.” And Bellamy’s descendants have said he wouldn’t have wanted the ‘God’ phrase added.

The absence of “under God” in the Pledge wouldn’t be the only thing about Bellamy that would spark a presidential tweetstorm today. While Trump likes to label his Democratic opponents as “socialists,” Bellamy actually was one.

Francis Bellamy

In fact, he started writing for Youth’s Companion after being pushed out of the pulpit at Bethany Baptist Church in Boston. Apparently not everyone agreed with his declarations about “Jesus the Socialist” as he served as vice president of the Society of Christian Socialists. He also wrote for Society’s newspaper The Dawn. In a piece in the May 1890 issue on advancing the cause of Christian socialism, he urged pastors to preach on socialistic themes — and even seemed to predict his own church problems to come.

“The pastor, perhaps, cannot carry his congregation with him, should he avow himself a Christian Socialist; but he can preach frequently on themes having a decided bearing on the relation of Christ to current economics,” Bellamy wrote, “and he can gather around him a select class of his acquaintances, from within and from without his church, who can study the questions of economics from the religious point of view.”

Later in that piece, he defined Christian socialism as “the science of the Golden Rule applied to economic relations.” But he noted it’s difficult to advance since “the law of selfishness has been so thoroughly centered in the old and the current maxims of business,” so they must “work in educating the public mind to right convictions on the place of righteousness in economics.”

This ideology often led Bellamy to a focus on prioritizing the needs of people, not just in economics but also in governance. For instance, in the May 1, 1891 issue of The Dawn, Bellamy wrote about how to improve municipal government to be more efficient and less corrupt.

“The city is a social organism in which the individuals are related to each other in certain common needs. It is time the American city become conscious of itself, and of its mission as a business enterprise for the good of its citizens,” he wrote. “But, before all, after all, under all, trust the people. Trust them with an undismayed, invincible trust. Make the people trustworthy by putting more trust in them.”

More than two decades after Bellamy’s death, a significant shift came to his Pledge. At the urging of President Dwight D. Eisenhower after listening to a Presbyterian sermon, Congress added “under God” in 1954 as the nation found itself in the Cold War with the atheistic, socialist Soviet Union. With ‘God’ in the Pledge, the U.S. increased its rhetorical arsenal in the global struggle.

Now many people see ‘God’ as a natural part of the Pledge. When Trump tweeted another critique of the DNC on Sunday as he prepared to spend the morning golfing, he claimed the absence of “under God” from the Pledge at the two caucus meetings “sounded not only strange, but terrible.” Yet, for nearly half its life, that’s exactly how the Pledge always sounded.

More than six decades after in the insertion of “under God” — and more than 12 decades since Bellamy wrote the Pledge for Columbus Day flag sales — the phrase “under God” has survived court challenges, Columbus statues are being beheaded amid protests, and the nation’s government is run by a wealthy businessman with numerous associates arrested for corruption. Bellamy would probably have lots to say about all of that.