BURLINGTON, Vt. (AP) — Some Vermont religious leaders are asking the state to confront its role as a location where Black people were once held as slaves and remember those individuals.

Rabbi Amy Small of Burlington’s Ohavi Zedek Synagogue says the common myth is that there were no enslaved individuals in Vermont. But the historical record says the daughter of Ethan Allen, who helped found Vermont in the late 1700s, enslaved two Black people at a home in Burlington.

Small is part of a new effort to commemorate the lives of Lavinia and Francis Parker, a mother and son enslaved by Allen’s daughter Lucy Caroline Allen Hitchcock.

“And that’s a hard pill to swallow,” Small told Vermont Public Radio. “But it’s part of the history that we have to recognize and repair.”

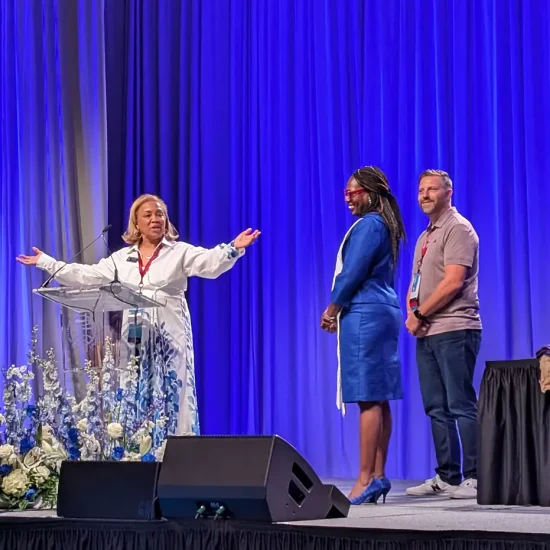

Small is working with Arnold Thomas, the pastor of the pastor of Good Lutheran Church in Jericho. He is the first African American person to serve as denominational leader for the United Church of Christ in Vermont.

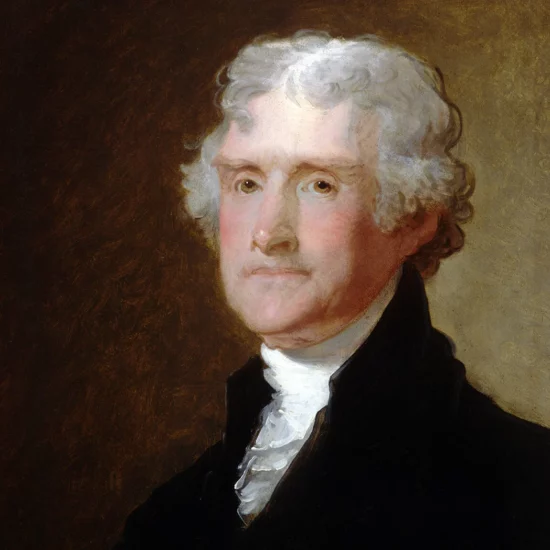

An art installation of slaves at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice by artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo in Montgomery, Alabama. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

“And there is a dark side of our history that we have to accept, embrace,” Thomas said. “And knowing this, where do we go from here to address who we are today, to address the lingering elements of racism, and the lingering elements of segregation?”

Vermont prides itself on being the first state to abolish slavery, but historical records document numerous instances of forced servitude well after the state’s constitution partially banned the practice, said Vermont historian Jeff Potash.

“There were probably 50 to 150 instances of slaves being brought to Vermont,” he said.

Potash said Allen is known to have had Black servants, but it’s unclear whether they were formally enslaved.

“One of our great founding fathers and his family can basically be shown to be part of this larger … willingness on the part of Vermonters to look the other way, and to pretend as though slavery doesn’t operate within their midst,” Potash said.

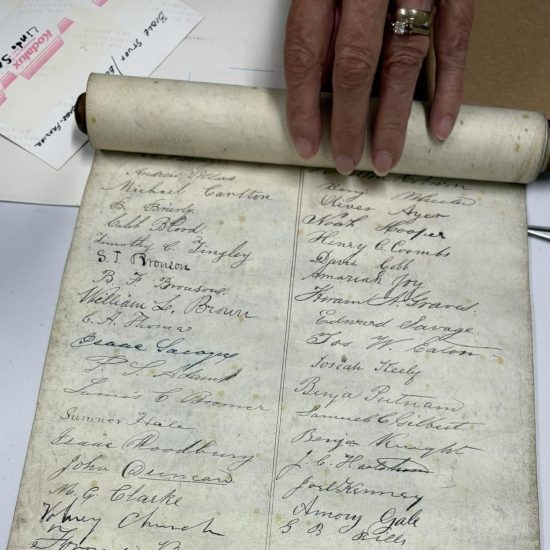

Using old maps Potash found the spot where Lavinia and Francis Parker lived, at the corner of St. Paul and Main Street in Burlington.

A plaque called a “Stopping Stone,” a brass plaque will be placed at the location.

The “Stopping Stones” are part of a project founded by another Ohavi Zedek member, Paul Growald. He modeled the project after an initiative in Germany, where brass plaques have been placed at the last known residences of victims of the Holocaust.

Next month, he’ll unveil brass plaques, set in Vermont granite, honoring the Parkers.

“We want people to stop and reflect that these were individual people who had agency, they had loves, they had lives and they made enormous contributions,” he said.