(RNS) — People who identify as highly spiritual are more likely to say it’s important to make a difference in their communities and contribute to the greater good, a broad new study on American spirituality finds.

The study, “What Does Spirituality Mean to Us?,” found that 86% of Americans identify as spiritual to some extent. It also found that the more people define their spirituality through connection — to a higher power or to humanity at large — the more likely they are to volunteer, donate and vote.

Funded by the Kalamazoo, Michigan, Fetzer Institute, whose mission is to build a spiritual foundation for a loving world, the study included a nationally representative survey of 3,609 people, as well as 16 focus groups that met in 2018 and 2019. All the research was done before the coronavirus pandemic. (Fetzer is a past funder of Religion News Service projects.)

“What the Fetzer study has uncovered is how much people are talking about connection when they talk about spirituality — connection between the inner and outer world and with others in community,” said Omar M. McRoberts, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago and an adviser to the study. “Spirituality is not a solipsistic endeavor where it’s just about individual experience or elevation.”

Still, only 45% of respondents said spirituality influences their political views; 36% said their spirituality influences their political actions, and 41% said their spirituality leads them to hold politicians accountable.

In focus groups, the report said, people were ambivalent about the relationship between spirituality and voting and weren’t sure the two should be connected. Some described voting as a pragmatic choice based in logic or individual preference. Others said it was a profane rather than sacred act.

The report collected information about respondents’ political affiliations but did not provide that analysis in its report.

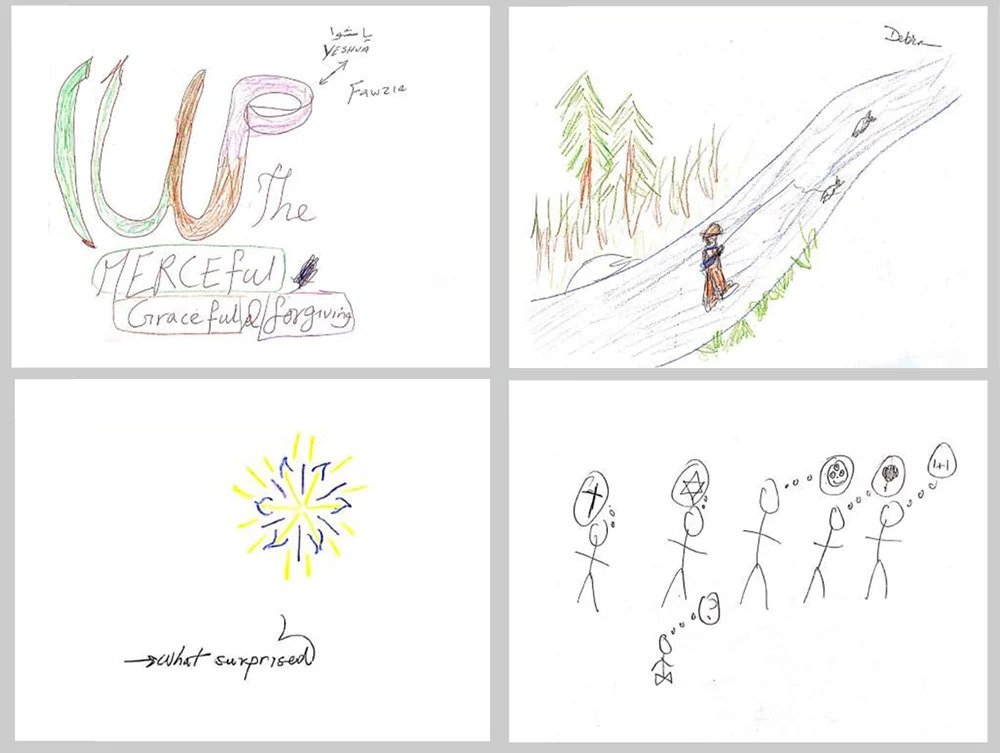

Drawings made for the study, “What Does Spirituality Mean to Us?” (Fetzer Institute/Religion News Service)

Spirituality is a burgeoning field of study in academia, especially as loyalty to religious denominations and institutions wanes. The past few decades have seen a rise of the “spiritual-but-not-religious” category as well as those who say they have no religious preference, the so-called nones.

From yoga classes to mindfulness practices, spiritual loyalties appear to be transferring from old institutions to various new ones.

But Nancy Ammerman, professor of sociology emerita at Boston College and a reviewer for the study, said there’s a lot of overlap between people who say they are religious and those who say they are spiritual. Indeed, the study found that 70% of respondents consider themselves both spiritual and religious. Just 16% said they were only spiritual; 3% said they were “only religious.”

Since multiple studies have shown that participation in religious communities is one of the primary drivers of civic engagement, it’s not clear whether spirituality or religion was moving people toward civic action.

“You end up having a finding that in effect tells you two things at once,” Ammerman said. “It’s framing things in terms of the effect of spirituality, but sitting behind that spirituality is the participation in religious communities that strengthens and sustains the spirituality.”

One of the study’s innovations was to ferret out what Americans consider spirituality to mean. The term is vague and can mean a lot of different things. The study had respondents draw what spirituality means to them in addition to trying to put it in words.

Some common illustrations captured symbols of the natural world (trees, clouds), as well as peace, love, a divine being, or a relationship with others. Asked to describe spiritual people in words, respondents chose positive attributes: happy and joyful; calm, and centered; compassionate and caring.

“It gives social scientists and people interested in this a huge amount of material to work with that doesn’t involve just giving people a set of predetermined responses that they have to put themselves in different boxes but allows people to speak for themselves about what spirituality means to them,” said Ruth Braunstein, a professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut who served as an adviser to the study.

In keeping with past studies, the Fetzer study found that spirituality has a positive valence with the American public. It was something people were working toward, something that could help them become a better version of themselves.

“People are becoming more spiritual as they age. There’s this aspirational quality to it,” said Gillian Gonda, a program director at the Fetzer Institute. “The more someone is spiritual, the more they aspire to be spiritual. It seems to be a never-ending search and journey that deepens for people over time.”