I knew all the baggage that came with the word, especially following the 2016 election of Donald Trump, where 81% of self-identifying White evangelicals voted for him. But I felt a responsibility to the word, and to my people.

One can’t simply wish or pretend away what they are, I thought. Even though I felt confused, heartbroken, and betrayed by the marriage of nationalism and Christianity I saw on full display in my community, that didn’t make me a sudden outsider. I simply was an evangelical; I had been born one — a home-schooled pastor’s kid who went to a Bible college to be a missionary — and I would remain one (until I got kicked out, I joked with my friends).

As a freelance writer who wrote primarily for evangelical audiences, I thought maybe I had a unique opportunity to evangelize my own people. They were, after all, the ones who raised me to love God and read the Bible, to become a disciple of Jesus. Surely they might be open to seeing how their views on immigration, police brutality, war, unchecked capitalism, the prison industrial complex, and more might be at odds with the message of Jesus?

I should have believed my community when they told me over and over again exactly who they are.

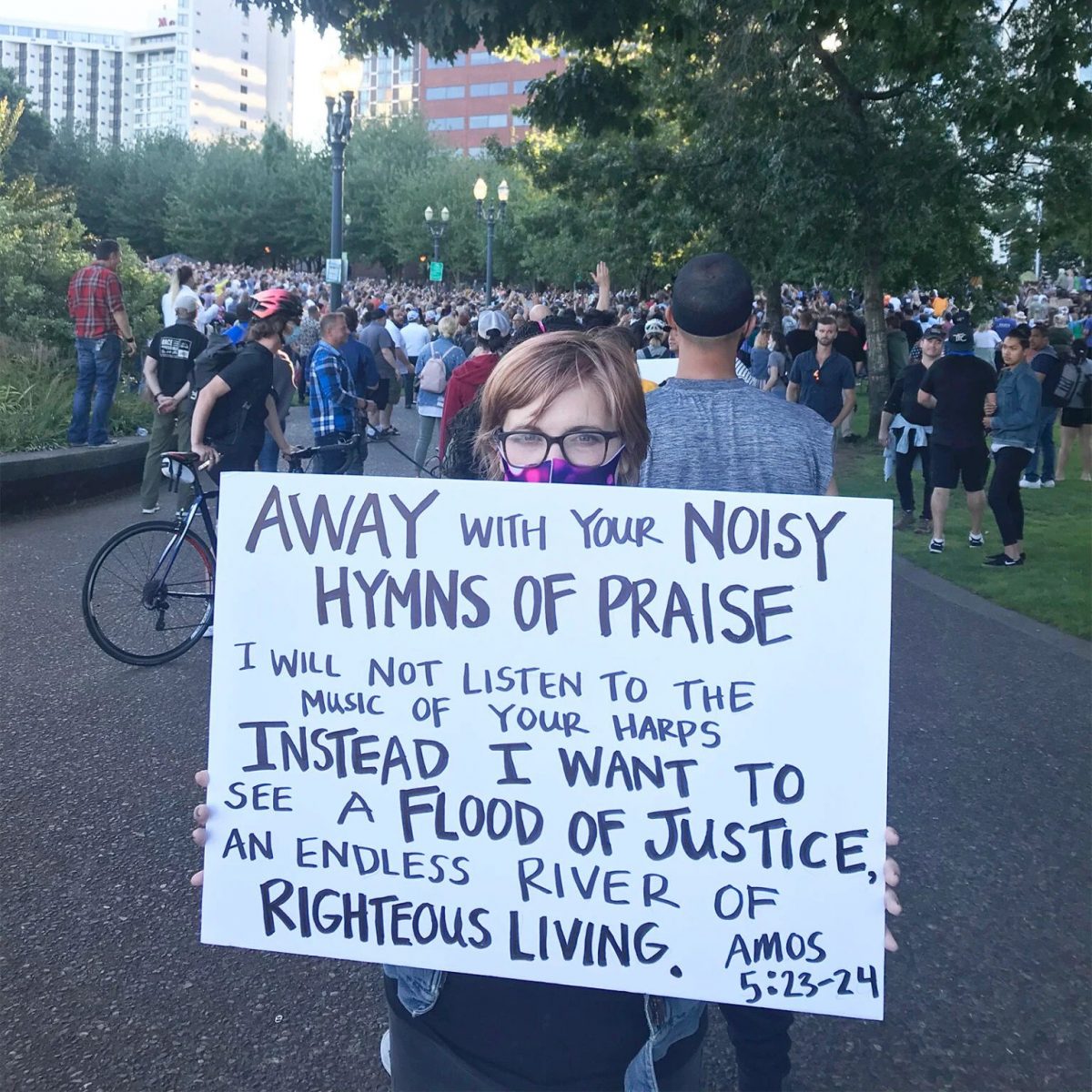

I live in Portland, Oregon, which has been making national and global news for the Black Lives Matter protests going on for more than three months now. Along with my Tuesday night prayer ladies, I joined in with many others in the city to put our bodies on the line to demand a change in our racist policing system. I went as my whole Christian self, holding a sign that said “Mother Mary lost a son to state violence.” I was tear-gassed, charged by officers in full riot gear and shot at with rubber bullets and flash bangs.

While the violence of the police was horrible, my main takeaway from being involved in multiple protests was how much like church they felt — how we chanted and sang and moved our feet. How people looked out for each other — with food and jokes and songs and medical care. How we were bonded together in our belief that another world was possible.

Because of my experience at the protests, when I heard that a worship leader from Southern California was coming to Portland to hold a “riots to revival” concert downtown, I was immediately suspicious. The event, organized by a church in Vancouver, Washington, across the river, was being heavily promoted by charismatic and evangelical Christians as a chance to push back against the state laws forbidding Christians from gathering in church to sing during COVID-19.

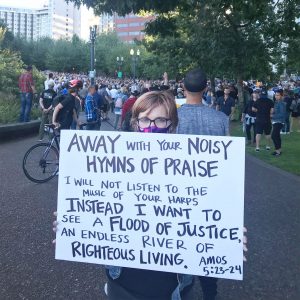

I decided to attend, along with my husband, and support my friend Beatrix who was organizing a counterprotest. My motivation was simple: I thought it was incredibly disrespectful to characterize the protests for Black Lives Matter as “riots” and to hold this concert in the very space where people had been crying out for justice — and being brutalized by the police just for doing that. We wanted to hold signs and identify ourselves as Christians while also not letting people forget about the Black Lives Matter protests that were continuing to go on.

D.L. Mayfield protests a Sean Feucht concert in Portland, Oregon, in August 2020. (Candyce Wani/Religion News Service)

Just standing on the edge of the worshiping crowd was enough to draw the ire and attention of many folks. For almost two hours I was constantly confronted, yelled at, livestreamed, prayed over, and told I was not a real Christian (for the record, I was simply holding a sign that had a Bible verse on it).

I was not prepared for how much worse this would be than tear gas. I was not prepared for the pit in my stomach as I saw the thousands of Christians gathered, without masks, triumphantly singing songs to God, hands in the air and all eyes turned toward the worship leader on stage.

The person leading the event, Sean Feucht, has a mass of curly blond hair and is known for being opportunistic when it comes to marrying politics with worship leading. Feucht, a vocal Trump supporter and former congressional candidate, has been raising money to travel to spots in the United States where horrific deaths at the hands of police have taken place or where long-term protests in support of Black Lives Matter are going on. He sings happy songs about God being on his side, the speakers turned up to full volume in order to literally drown out the protesters’ cries for justice.

I knew almost every word to the songs the group was singing — but I could not bring myself to sing along.

Surrounded on all sides by people with arms raised high, eyes closed, joy and certainty shining on the faces of the true believers, it hit me: We read the same Bible, and we all call ourselves Christians. But we are not singing to the same God. I could no longer pretend otherwise.

I lost my religion that day, in that crowd of worshipers.

I lost the word “evangelical” as I realized I was surrounded by people who truly believed they were proclaiming the good news. Yet on the edges of their concert, young people of color were begging for them to listen to their grief instead of shouting over it.

I can no longer call myself an evangelical, because what defines a White evangelical in the United States has become a longing for an authoritarian state where Christianity is prioritized and privileged.

This kind of Christian nationalism is entirely at odds with the gospel of Jesus, who told us right from the beginning that he was going to be good news to the poor, the imprisoned, the sick, and the oppressed — and that he would be bad news for people who longed to clutch at power and safety and affluence at the expense of their neighbor.

I think the long-term consequences of White evangelicals longing to secure their own power and influence will ultimately backfire spectacularly — we already see people leaving the church in droves, and I expect that number to multiply.

If I am being honest with myself, I know I was kicked out of the evangelical world a while ago. I was told I could not write for Christianity Today anymore because of my stance on LGBTQIA issues. I left my church in Portland after a long and drawn-out period of trying to advocate for equality for women and the LGBTQIA community. And now I routinely have evangelicals, both in person and online, question the state of my salvation because I support the Black Lives Matter movement.

I don’t know what to call myself anymore, but that’s OK. Whatever comes next, it won’t be something I need to create out of my bare hands, something I need to lead or something to reform.

I am still a Christian, and I still have hope for God’s dream of the world coming true in small ways, even in my own lifetime.

But this hope comes not from my fellow evangelicals, singing their loud songs to a small god they hope to control. No, it is showing up in all the unexpected places Jesus always told us to look, and finding God already at work there in so many places and in so many ways.

I’m finding a path forward in my life with Jesus by looking to the example of anarchists and activists, middle-age moms and veterans, the young kids protesting on the street every night, people experiencing homelessness, in immigrant and refugee faith communities, in the Black church and mujerista theologians, in the faith of those who have always been marginalized and therefore are the only ones who can truly envision a new path forward. I’m going to listen to their songs, their chants, and their prayers.

I’m going to keep showing up to their protests — and trust Jesus when he says I will be blessed if I choose to follow them.

D.L. Mayfield is a writer and activist who has spent over a decade working with refugee communities in the United States. She is the author of the newly released book “The Myth of the American Dream.”