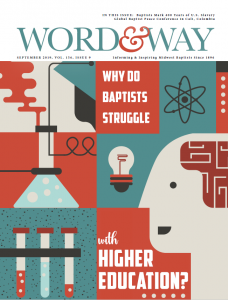

(Note: This piece first appeared as the cover story for the September 2019 issue of Word&Way magazine. It is now being published online for the first time 13 months later, with minor edits to update date references. The print edition also included a timeline highlighting 16 controversies since 1939 during which more than 40 professors at nine different Baptist schools were targeted for dismissal.)

My maternal grandfather, a Baptist pastor in Missouri and Iowa for four decades, liked to joke. One of those wisecracks came as he asked me when I was young, “What’s the difference between a Baptist and a Methodist?” After I shrugged and looked at him in anticipation of the answer, he proclaimed, “A Methodist is a Baptist who can read!”

I laughed a bit, but mostly at how he laughed at his own borrowed joke. I didn’t quite get it at the time. After all, he was not only a Baptist minister but a public school teacher for four decades, so clearly he cared about reading and the other parts of education. And both my Baptist parents had college degrees. And the pastors at my home church all had graduate degrees from seminaries.

Although I’ve since learned the history behind the joke as frontier Baptists did, in fact, lag behind Methodists in education, I’ve also come to appreciate that my grandfather saw a nugget of truth even in more recent decades. While Baptists can read, we do often still nurse a suspicion of higher education.

I’ve thought about that old joke recently as my undergraduate alma mater, Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Missouri, finds itself embroiled in a controversy about the alleged heresies taught by several professors. The news broke in December 2018 after SBU fired religion professor Clint Bass for violating the faculty handbook after he met secretly with Missouri Baptist Convention leaders in an effort to push out other professors in SBU’s Redford College of Theology and Ministry. Although the trustee committee that considered his appeal unanimously agreed with his dismissal, he and his supporters have continued to throw stones at the other professors.

I had some of those professors in classes and I went to school at the same time as the fired professor who sparked this public heresy trial. To me, the issue is clear and the charges of liberalism run amok at SBU are laughable. But I also see something larger at play, something at the heart of that old joke my grandfather told.

Sock It To Me

Shortly before I started my undergraduate studies at SBU, I preached at my home church in Jefferson City, Missouri. I had preached there — and a couple other churches — a few times in high school. This was kind of my sending-off service to preach one more time before leaving town. I don’t think it was meant as a baseline measure to see if I actually got better when I came back from SBU. But at least one member of the church wondered about that.

After the service, a man came up to tell me how much he liked my sermon. He asked if he heard correctly that I’d soon study theology at college. After I confirmed that, he responded, “Well, don’t let them mess you up there, just keep preaching the Bible. “

I think I mumbled something along the lines of “sure, I’ll keep it up,” but I don’t recall. I just remember my surprise at his concern. Why would learning more about the Bible be viewed as a risk to my preaching? Once at school, I merely ignored the comment and dove into my studies, growing in my understanding of the Bible and my ability to preach it.

By my junior year, however, I experienced how Baptists can turn on professors. Two leaders of SBU’s Redford College — Dean H.K. Neely and Associate Dean Scott Langston — found themselves under attack for speaking at the opening meeting of the Baptist General Convention of Missouri (now known as Churchnet), which represented a more moderate expression among Baptists in Missouri who, among other things, did not approve of lawsuits against Baptist ministry organizations (like Word&Way).

Controversy quickly erupted for their involvement at a Baptist gathering. A few months later, Neely left SBU — where he had served in two stints for a total of two decades — after being forced out. He then served as the first executive director of the BGCM (and then hired me the next year as I graduated). Two years later, Langston left SBU after being denied a promotion. In 2019, an SBU trustee inaccurately attacked Neely and Langston as he recounted their removals and urged support for Bass, apparently seeing the current controversy as related to the earlier purge.

But like a game of “Telephone,” the story of Neely and especially Langston morphed from reality. For Langston, the real problems started when he agreed to an interview with a then-Baptist Press reporter now known for false claims and sloppy reporting.

While Baptists can read, we do often still nurse a suspicion of higher education.

I actually attended that first BGCM meeting in 2002 as a ministry student curious about this new Baptist group. And I went so I could write about it for SBU’s student newspaper, The Omnibus. (My article, though factual, would ultimately end my journalism career at The Omnibus because it covered the controversial meeting.)

As a poor college student, I crashed on the floor of a friend of my sister, since she attended a school in St. Louis not far from the meeting at Fee Fee Baptist Church, the oldest Protestant church west of the Mississippi (a church my ancestors helped start). After an evening session, I was talking to Langston, one of the few people there that I knew. I had him in class and appreciated his scholarly understanding of the Old Testament.

As we chatted briefly after the session, a reporter walked up between us and said he wanted to interview Langston, so I excused myself. I wish I would have stayed — as a witness.

The writer for Southern Baptist Convention’s Baptist Press sent to the cover the story apparently peppered Langston with a number of questions unrelated to Langston’s Bible studies he presented at the meeting. Did he believe in the virgin birth of Jesus? Did he believe in a literal, bodily resurrection? Did he believe Jonah was a literal account of a guy swallowed by a large fish?

I now recognize the point of such questions. These “gotcha” questions are attempts to quickly dismiss someone as a heretical liberal, rather than engage in what they actually said at the event and without any room for nuance. But Langston answered them honestly.

We don’t know exactly what Langston said. He didn’t record it and I had already left. The Baptist Press reporter gave a response about Jonah from Langston, who called it inaccurate and taken out of context.

“My perception of that article is that it was poorly done,” Langston later told Word&Way. “I tried to point out that the article did not represent what I said.”

“I think what’s happened is unethical, unbiblical, and unChristian. I don’t want to be associated with that,” he added. “What I’m reacting to is not the theological issue … but the way people have been treated.”

And there’s good reason to believe Langston. That same reporter, Todd Starnes, was fired by the Baptist Press one year later for misquoting someone else.

In April 2003, Starnes interviewed then-U.S. Secretary of Education Rod Paige. Remarks reported by Starnes quickly sparked controversy in national media as it seemed Paige endorsed sectarian content in public schools and expressed preference for Christian schools over the public schools for which he was supposed to advocate. Paige insisted he was misquoted, and the Education Department released a transcript from a recording of the interview that showed numerous cases where the quotes in Starnes’s report were inaccurate or taken out of context. The Baptist Press then admitted “factual and contextual errors” and said Starnes “no longer will be employed to write for the Baptist Press.”

I think what’s happened is unethical, unbiblical, and unChristian. I don’t want to be associated with that. … What I’m reacting to is not the theological issue … but the way people have been treated.

Yet, Starnes quickly recovered from this serious journalistic error. After leading communications at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee — and then working at a couple local radio stations, Starnes was hired by Fox News Radio in 2005, where he remained until let go in October 2019 after he and guest Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, claimed Democrats worship a false god. Starnes has continued his radio show on his own.

At Fox, Starnes quickly gained a reputation as one of the more controversial commentators, including his advocacy for violence against protesters, his racist and anti-immigrant remarks, and his pushing of conspiracy theories. And many of his reports have been criticized by the independent PolitiFact and other factcheckers as false.

Meanwhile, just as Fox News Radio apparently did not find Starnes’s firing meaningful, neither did those at SBU who considered Langston’s promotion. Despite his claim that Starnes misquoted him just like with Paige, Langston did not receive a promotion and left the school in 2004. Langston went to Texas to teach as an adjunct professor, published his second book the year after he left SBU, and has continued to win awards for his scholarship.

It would be hard to find two people more different in personality, tone, and depth of writing. And yet, while Langston remains in the Baptist desert, Baptist Press even started running some of Starnes’s Fox News Radio reports and hosted Starnes as the keynote speaker for the 2010 Baptist Press Collegiate Journalism Conference.

That old joke about Baptists and Methodists is hitting too close to home to be funny anymore.

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before

The controversy surrounding Neely and Langston during my last three semesters at SBU provided my first education in Baptist struggles with higher education. I’ve since learned it had already played out similarly in several other contexts. Over the past several decades, dozens of professors have been fired or pressured to resign at various Baptist schools, including all six SBC seminaries and schools affiliated with various state conventions and the American Baptist Churches USA.

In fact, concerns about professors helped fuel the rightward shift in the SBC that started to win elections four decades ago under the leadership of Paige Patterson and Paul Pressler. As Gregory Wills, a church history professor who moved in 2019 from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, to Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, wrote in a 2010 article in the Southern Baptist Journal of Theology, “The seminaries were the focal point of the struggles” during the SBC conflict.

“By the 1960s conservatives became convinced that liberalism originating from the seminaries gravely imperiled the denomination. They agitated against liberal professors and successfully pressured the seminaries to dismiss some of their most vulnerable faculty members,” he added. “The chief impact on the seminaries was to frighten the faculties into becoming more cautious in their writings and public statements.”

As Wills noted, the internal SBC conflict usually centered on the words and roles of theological schools and their professors. Over the decades leading up the 1979 success by the Patterson-Pressler coalition, those two and other fundamentalist Southern Baptists crusaded against various professors. And they often found success in either forcing administrators to fire an “errant” professor or pressure the beleaguered professor to resign to take a position at a non-SBC school.

The critics of SBC seminaries also started their own alternative schools. W.A. Criswell, pastor of First Baptist church in Dallas, Texas, launched the Criswell Bible Institute (now known as Criswell College) in 1970 just as he finished his tenure as SBC president. Patterson would serve as president of the school during the SBC battle, from 1975 until 1992. After that, Patterson switched to head two of the SBC seminaries, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, N.C., and then Southwestern. The outside critic had taken over.

Other alternative SBC schools also started in the years before the Patterson-Pressler coalition shifted the SBC to offer a different theological perspective and approach to higher education. For instance, Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary in Cordova, Tennessee, started in 1971 as the School of the Prophets. And even though the struggle to take over the SBC and remake the seminaries was effective, schools like Criswell and Mid-America remain open. Since the success of the Patterson-Pressler coalition, those who left to join the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship have also created seminaries — like Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond (started in 1989 and closed in 2019) and Baptist Seminary of Kentucky (started in 1996).

The chief impact on the seminaries was to frighten the faculties into becoming more cautious in their writings and public statements.

In the decades leading up to the SBC shift, as Wills noted, the writings and public statements were what usually got professors in trouble at Baptist schools — not their teaching per se, but their interviews, sermons, and especially books. Perhaps the most well-known of these was the case of Ralph Elliott, the first professor hired at the new Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Mo. He published his book The Message of Genesis in 1961, just three years after moving from SBTS to MBTS.

The book, in which he treated the first 11 chapters of Genesis as not literal, quickly sparked controversy across the SBC, leading to calls for revising the SBC’s confessional statement and thus resulting in the Baptist Faith & Message 1963. MBTS trustees initially supported Elliott, but the next year some of the trustees were replaced — even though eligible for reelection. The new trustee board fired Elliott for alleged “insubordination.”

Yet, even before Elliott’s book, some Baptists in Missouri and Kansas were already on a witch hunt to discover if any “liberal” professors taught at the new school — and pastors in Oklahoma quickly joined the fight after the book’s publication. A prominent St. Louis pastor solicited classroom notes from students, foreshadowing a tactic that would be used by the Patterson-Pressler coalition during the SBC struggle in the 1980s and 1990s. Pressler quickly emerged as a key critic of Elliott. Another key fundamentalist critic, Owen White, won the SBC presidency in 1963 in part due to his advocacy to oust Elliott.

Elliott, who after his time at MBTS became an American Baptist pastor and later dean of ABCUSA-affiliated Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School in Rochester, New York, wrote about the conflict in a 2005 book published by Mercer University Press, The Genesis Controversy. He noted that shortly after his earlier book’s publication, many inaccurate statements about him and his beliefs spread.

“I was surprised to learn, through letters received, radio talks, rumors, and all sorts of ways, that I did not accept the classical statement of the divine-humanness of Jesus and that I was an unbeliever with regard to Jesus and the Christian gospel,” he reflected. “It was during those days that I learned how gullible much of the church community was and how ready to follow anything that was negative.”

He insisted his 1961 book was quite conservative and contrasted it with liberal approaches to Genesis, but the “liberal” label quickly stuck to him. Baptist churches in the region canceled invites to preach and passed resolutions calling for his firing. The Missouri Baptist Convention removed him from the 1961 annual meeting program. And someone even threw an explosive device from a speeding car that damaged the front door of his house.

“Many Southern Baptists considered anything not encountered before as ‘liberal,’” he wrote. “‘Liberal’ was and is, of course, a dirty word in the Southern Baptist context.”

Elliott’s experience with being “given the appellation of ‘liberal’ or even ‘heretic’” for having “violated the machine-stamped mold,” captures an important aspect of Baptist struggles with academic freedom. That attempts to oust professors at Baptist schools nearly always come from the right.

Elliott believed the conflict about him was really a question about “the nature of theological education” and whether it is “education or indoctrination.” Thus, for Elliott, the action of the MBTS trustees to fire him signaled a new era in Southern Baptist life that threatened higher education.

“Their action was a violation of all acceptable academic standards used as a guide for educational institutions,” he wrote. “All Baptist professors were placed under threat. That threat has increased across the years, and professors in every Southern Baptist seminary have lost any sense of liberty and freedom.”

All Baptist professors were placed under threat. That threat has increased across the years, and professors in every Southern Baptist seminary have lost any sense of liberty and freedom.

Elliott was not the first — and definitely not the last — professorial scalp collected in various Baptist conflicts. And while some want to consider these cases as merely theological struggles, collectively they say something broader about Baptists and higher education. What is the purpose of education? How much academic freedom should professors have in their scholarship and lectures? And who gets to decide what is “acceptable” for a professor to say.

Knock, Knock

Adrian Rogers, the first SBC president from the Patterson-Pressler coalition, famously declared while SBC president: “If Southern Baptists believe that pickles have souls, then professors must teach that.” The worldview behind his tongue-in-cheek example gets to the heart of the debate between education and indoctrination.

If the SBC passes a resolution declaring something that is in conflict with the Bible, should professors in turn teach that or what those professors feel the Bible actually teaches? For Rogers, Patterson, Pressler, and the other new leaders of the SBC, the majority vote decides truth. Professors should, therefore, toe the party line and produce more clones.

“Under this idea, we would have spiritual masters to tell us what to teach, what to learn, and what to believe,” declared Bill Underwood, then-interim president at Baylor University, during a 2005 graduation ceremony after quoting Rogers on pickles. “Christian universities must also equip our students with the critical thinking skills needed for a lifelong pursuit of truth. This requires encouraging our students to think for themselves and then to test their ideas in free and open discourse with others, even ideas that are controversial — even ideas that challenge prevailing viewpoints.”

“This free exchange of ideas is most likely to lead to the discovery of truth. That’s the idea behind the First Amendment,” added Underwood, who is now president of Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. “If we are to be a great Christian university, we cannot be afraid to pursue the course of truth, wherever that course might lead. Indeed, if our pursuit of truth leads us to question our existing view of God, it may just be that God is trying to tell us something.”

Ultimately, Underwood’s vision of Christian higher education remains opposed by those in the vein of Rogers who keep knocking on professors. This push for teaching pickled theology continues at my alma mater. Once again, there is an effort to remove conservative professors for supposedly “liberal” and “heretical” beliefs. And, once again, the issue is really about the nature of education.

If we are to be a great Christian university, we cannot be afraid to pursue the course of truth, wherever that course might lead. Indeed, if our pursuit of truth leads us to question our existing view of God, it may just be that God is trying to tell us something.

Zach Manis, one of the SBU professors most attacked by Bass and others, wrote back in December 2018 that “the heart of the matter in all of this” is this question, “What is the purpose of a Christian liberal arts education?” Manis saw his critics as wanting “the indoctrination model,” but he answered the question differently.

“One of the primary tasks of Christian education — including theological education,” Manis wrote, “is that of equipping students to think for themselves about deep questions of enduring significance for their lives, including (especially) their faith.”

“This is not relativism, or subjectivism, or postmodernism, or any of the other boogeymen that haunt the imaginations of Christian fundamentalists. This is, quite simply, what it is to engage in critical thinking, and what it is to equip students to do the same,” he added. “My task as a philosophy teacher is to equip my students to develop and defend their own views. This is what it is to begin to think critically. And the fostering of this ability is among the principle ends of a Christian liberal arts university.”

In 2020, SBU decided to eliminate the philosophy program and Manis’s position at the end of the current academic year.

This is not relativism, or subjectivism, or postmodernism, or any of the other boogeymen that haunt the imaginations of Christian fundamentalists. This is, quite simply, what it is to engage in critical thinking, and what it is to equip students to do the same.

The most attacked of the professors, then-Redford Dean Rodney Reeves, announced in August 2019 he would leave SBU to assume the pastorate of a church in Arkansas. As a former student of Reeves, I wish the best for him and see his departure as a significant loss for SBU. If a professor like Reeves is not welcome in the Baptist academy, then Baptists do, indeed, have a higher education problem. It seems he was prophetic in his first public statement about the controversy in December 2018.

“The damage that has been done to me, my family and friends, my colleagues at SBU, the administration, and the entire university will be evident for years,” he wrote. “When it comes to higher theological education, some people tend to want to believe the worst about you.”

When I taught at a public university in Virginia for several years, some of my friends at church asked why I didn’t teach at a Christian college. I usually just joked that this way I wouldn’t get fired for what I wrote about religion. But maybe, like that old quip about Methodists, it wasn’t really a joke.