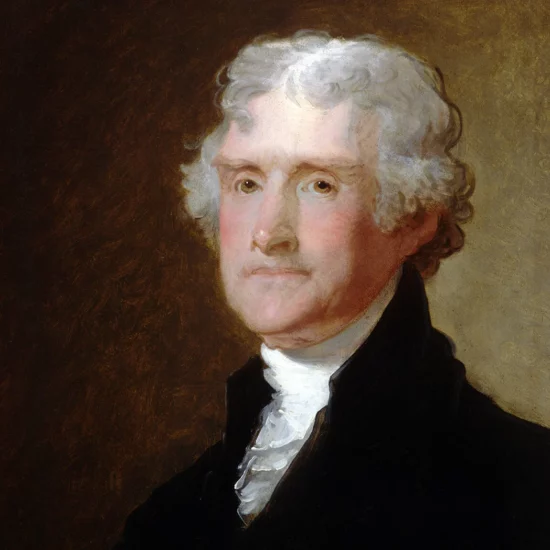

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — When the Junipero Serra statue in downtown Los Angeles was toppled four months ago, artist and community organizer Joel Garcia was among those who cried, prayed and celebrated in a Native American ceremony. Activists removed the monument to the 18th-century Franciscan missionary because it symbolizes to many an imperial conquest that enslaved Native Americans.

Demonstrators prepare to pull down a Junipero Serra statue on June 20, 2020, in downtown Los Angeles at Father Serra Park. (Erick Iñiguez/Religion News Service)

“It was such a nurturing space that some folks for the first time were able to talk about some of that harm that exists in their families,” said Garcia.

Now, Garcia, along with Indigenous leaders, artists, and activists across the state, is contemplating what comes next.

In San Francisco, where statues of Serra and Ulysses. S. Grant were also brought down during this summer’s protests, the city’s arts commission has been examining which of its nearly 100 monuments and memorials should remain or be removed. But a separate New Monument Taskforce, led by Bay Area artists, recently released its own study, The Relic Report.

In Los Angeles, activists and Indigenous leaders took part in a series of public and virtual events between Oct.12-14, identifying the city by the name of the ancestral native village it is built on: “Yaangna, Beyond L.A. Indigenous Frameworks.” In the webinar, hosted by Monument Lab, a public art and history studio in Philadelphia, and the Goethe-Institut, the German government’s cultural outreach organization, participants discussed whether these monuments should be replaced.

Morning Star Gali, a member of the Ajumawi band of Pit River Tribe who is allied with the Statewide Coalition Against Racist Symbols, participated in the webinar. Gali was involved in efforts calling for the removal of the statues of Serra and John Sutter, a Gold Rush-era colonizer.

Now, she said, they’re looking into how to use these spaces as “spaces of healing and truth telling.”

“That looks like returning the land back to California Native people, having our own museums, cultural institutions where we’re able to tell our own truths and provide our own perspectives,” she said.

Cindi Alvitre, a Tongva descendant and educator, suggested that the replacements need not be human figures at all, proposing a field of ancestor poles: shapes carved from trees with the sacred colors of red, yellow, black and white flags that memorialize people who have died.

Visually, it would be “incredibly beautiful” for families to pay homage to their ancestors and would provide a center where people could gather, Alvitre said.

To Garcia, grappling with California’s troubled Native American history is still uncomfortable for many people.

“It just falls under deaf ears,” he said. “We don’t know what it looks like yet. We’re trying to figure it out.”

Garcia, a fellow with Monument Lab, visited Berlin, where he was taken aback by how openly people in Germany discussed their history of genocide.

“When I was in Berlin, the one thing I heard over and over again was this commitment to telling the truth, no matter how difficult it is,” he said.