ST. PAUL, Minn. (AP) — Reflecting on a polarized nation in the throes of a bitterly fought election, Stephanie Christoffels started the communal prayer at a fall training of her fellow Minnesota National Guard chaplains by reminding them of Christianity’s two greatest commandments: to love God and neighbor.

“It’s difficult to love our neighbors … to go on Facebook and see what they’re posting,” the Lutheran pastor and only female chaplain in the Minnesota Guard told the faith leaders in military fatigues, each with the cross insignia of a Christian chaplain and many with badges for service in combat zones. “It’s hard to love people that hate us.”

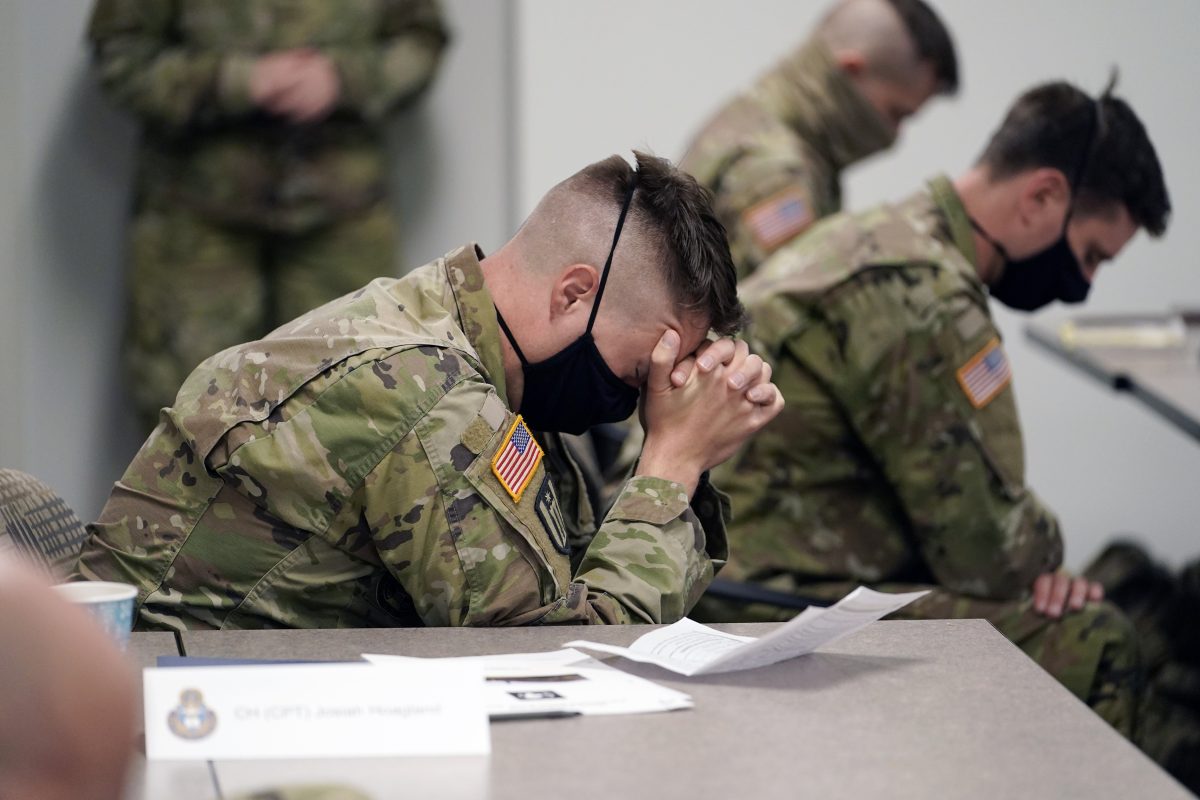

Minnesota National Guard chaplains bow during a prayer on Oct. 19, 2020 in St. Paul, Minnesota. (Jim Mone/Associated Press)

National Guard troops were deployed during this summer’s widespread unrest over racial injustice following George Floyd’s death in police custody in Minneapolis, and again this fall in the city as a surge in violent crime collided with heated debate over law enforcement and race.

Now the chaplains say they’re working on two main lessons learned from those tumultuous times: Building bridges within tense communities and bringing faith-grounded calm and comfort to the front lines whenever they may be mobilized again — possibly as soon as next March, when the officers charged in Floyd’s killing go on trial.

“The work isn’t done,” said Buddy Winn, the state chaplain and a Pentecostal pastor in the Twin Cities. “It’s about relationships … to establish some trust, to de-escalate threats. To people of faith I say, ‘pray hard.’”

The role of Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu faith leaders who serve as National Guard chaplains nationwide has grown more crucial, and more challenging, as thousands of soldiers and airmen, most of them in their 20s, find themselves mobilized not only for natural disasters and overseas conflicts but also domestic unrest.

When the protests erupted in Twin Cities neighborhoods following Floyd’s death, Minnesota’s governor authorized the state National Guard to fully activate for its largest domestic deployment in history.

Sam Houston, a Baptist pastor and the Minnesota National Guard’s only Black chaplain, said he saw protesters taunting some African American guard members — and heard soldiers agonize about wishing they could stand with demonstrators.

“You’re providing the opportunity for people to protest peacefully for you,” Houston advised them, adding that their role in serving was to ensure a safe environment.

“It’s only the people who were trying to break the law,” he said, “that needed to be concerned about the guard.”

Raised in an Army family, Houston plans to spend even more time on the front lines if activated again, “taking care of the soldiers and just praying for discernment, for what to do and what not to do … because as our commander put it, the only thing standing between a good day and a bad day is literally 6 pounds of pressure on the trigger.”

Michael Creagan, the state guard’s only Catholic chaplain, recalled how on a bright Saturday in late May, he was looking forward to celebrating Pentecost with the first public in-person services since lockdown. Instead, he was abruptly called up to join the approximately 10,000 other guard members being mobilized to help law enforcement protect hospitals, federal buildings, and the state Capitol.

It was at the Capitol that he celebrated Mass for troops bunking there, a few blocks from the worst of the damage St. Paul saw during the protests. For the nine days he was away from his parish and school, Creagan supplied soldiers with “piles” of rosaries — “they go fast,” he said of the Catholic devotional beads — and tried to provide some grace and “normalcy” through Mass and confession.

He’s preparing for a possible next time by readying a supply of sacred scriptures from a variety of faiths to better counsel troops from other religious traditions — the Quran, for example, for Muslim soldiers.

“It’s the basic right of the free practice of religion,” Creagan said. “We pluck them up and deploy them, but they need to have their rights protected.”

Winn said chaplains’ fundamental objective has remained unchanged since the first were put in paid Army positions in 1775: to provide pastoral care to their units. That includes everything from leading worship services to counseling the nonreligious, a group that in the Minnesota Guard represents about a third of members.

“You’re the pillar of spiritual resilience for your unit,” said Winn, who wears a bracelet engraved with the names of two Marines who were killed in Iraq in 2007 and whose bodies he retrieved from their forward operating base.

That kind of war-zone experience can help chaplains like him with another important duty: advising commanders on the impact religion might have on any mission. When that involves civil unrest, it means reminding commanders that “we’re not going out against an enemy,” Winn said.

Chaplains are also called to sensitize commanders to potential moral trauma among the troops, such as one case where Winn witnessed a young Black soldier being harangued by protesters for not being with them. And they can be especially useful in defusing such confrontations, as men and women of faith and because they do not carry weapons.

Chaplains wrestle with the same tensions as the regular guard members over being deployed to U.S. protests.

“It was really strange, being worried about myself in my own state,” said Christoffels, a mother of three who served in the Middle East before the summer callup. “We’re trained to do all this, but it’s just different when it’s your own turf.”

In the fall training at the St. Paul armory, she urged the two dozen chaplains to take care of themselves, take time to breathe and work to find some element of commonality even among people engaged in bitter confrontations, whether at a barricade or in the pews.

Christoffels closed her prayer by invoking God’s grace for chaplains, soldiers and civilians alike: “Help us when we’re having a difficult time loving people the way you want us to.”