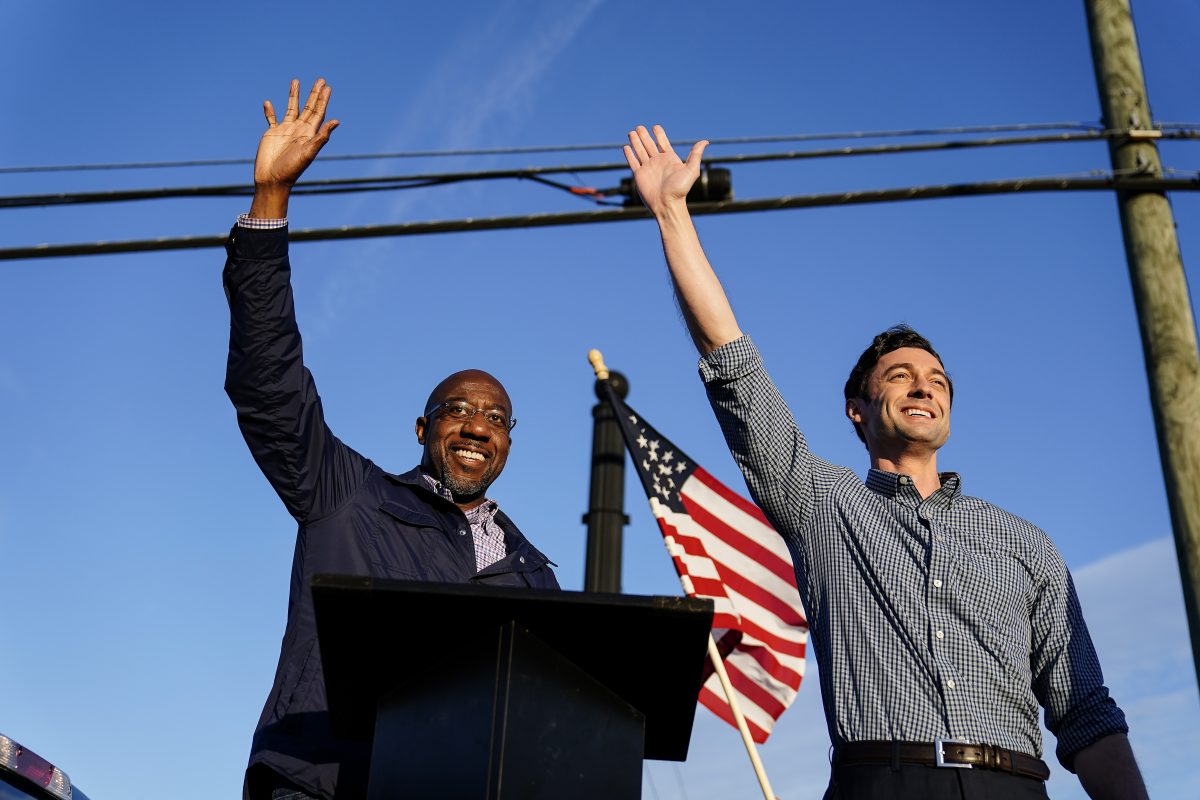

(THE CONVERSATION) — While campaigning for Republican U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler, U.S. Rep. Doug Collins – a former pastor – attacked her Democratic opponent, Rev. Raphael Warnock, the senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, for his views on abortion rights.

“There is no such thing as a pro-choice pastor,” Collins said of Warnock. “What you have is a lie from the bed of hell.”

Their differing views on abortion reflect a range of views on controversial political issues among American clergy. Yet what made the sparring so notable is the infrequency with which two pastor politicians are even in a position to confront one another.

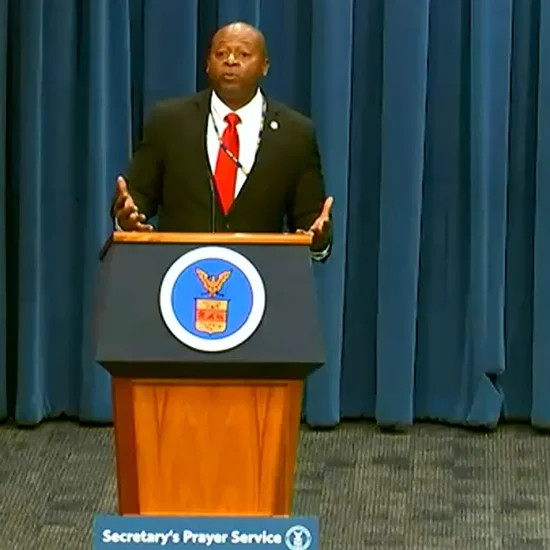

If Warnock were to win, he would join Republican Sen. James Lankford as one of two ordained ministers in the Senate chamber. Only about 2% of members of the U.S. House of Representatives are ordained ministers.

Their numbers are scarce despite the fact that members of the clergy often possess speaking skills, have an impulse to serve, and boast strong ties to their communities – all qualities that are useful in politics. Furthermore, Americans are among the most religious people in the Western world.

So why do so few clergy serve in Congress? And what kind of effect might this have on the priorities and policies that emerge from Washington, D.C.?

Lawyers, Business People Lead the Pack

In the “Congress and the Presidency” course that I teach, I discuss the prior professional careers of members of Congress and the way those backgrounds can influence lawmaking.

Almost half of U.S. senators worked as attorneys prior to their political careers, and 160 current members of the U.S. House of Representatives have law degrees. Other than politics, law is the most common former profession of Democrats in Congress, while business is the most common former profession of Republicans.

Lawyers in Congress can write legislation using language that can guide administrative agencies and judges, with an eye toward shielding laws from potential legal challenges. The downside of this practice is that legislative text can be weighed down in legal jargon that only other lawyers can understand.

Meanwhile, the growing ranks of Republican members of Congress with business backgrounds reflect the party’s ideological opposition to government regulation of the private sector.

Each party’s recent presidents reflect their orientation: The last three Republican presidents – Donald Trump, George W. Bush, and George H.W. Bush – all worked in business prior to entering politics. Once Joe Biden becomes president in January, he’ll join Democratic predecessors Barack Obama and Bill Clinton as having graduated from law school.

Members of the clergy, however, are far down the list of congressional occupations – behind agriculture, engineering, journalism, labor, medicine, real estate, and the military.

Only one former U.S. president, James Garfield, has ties to a previous life at the pulpit – and even those are tenuous. While he’s sometimes described as an ordained minister with the Disciples of Christ – and he did preach to congregations as a young man – there don’t appear to be any clear ordination records. His primary professions before entering politics were as a Civil War general, teacher, and attorney.

It’s possible that the lack of clergy members in Congress may bring less attention to spiritual issues in Washington. Morality may be deemed less important, while crafting public policies that help the less fortunate get short shrift.

At the same time, the clergy has long played an active role in American politics outside of elective office, usually working to influence policy and politicians. Prominent evangelical preachers Franklin Graham, James Dobson, and Kenneth Copeland all spoke out in favor of Donald Trump’s reelection this year.

Reverend Jesse Jackson and Rev. Al Sharpton have each run for the Democratic nomination for president, while Rev. William Barber has garnered attention in recent years for leading “Moral Mondays” protests to advocate for civil rights and progressive causes in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Legal & Papal Pushback

In the past, there have been legal and doctrinal restrictions on clergy members serving in government.

Up until the 1970s, several states had constitutional restrictions against clergy members serving in the state legislatures, which often serve as a stepping stone for candidates to run for national office. But in an 8-0 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1978 that such state restrictions violated the free exercise clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The decision allowed Rev. Paul McDaniel, a Baptist minister, to run to be a delegate to a Tennessee state constitutional convention.

Church policy can also discourage clergy running for office. Two Catholic priests who had served in the House of Representatives ended their candidacies in 1980 when Pope John Paul II declared that he would begin strictly enforcing a canon law that priests should not serve in public office.

One of them was Father Robert Drinan, who had served five terms as a U.S. representative from Massachusetts. Drinan was known nationally as a prominent opponent of the Vietnam War, and he had introduced the first impeachment resolution against President Richard Nixon. Drinan’s support of abortion rights was especially controversial among Catholic church leaders.

Another reason for low numbers of clergy in national elected office may be tied to the country’s longstanding tradition of separating religion from government. In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson famously wrote that the language of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution indicated “a wall of separation between Church & State.”

Religion and government are more closely intertwined in many other Western countries. For example, in the United Kingdom, 26 bishops who are leaders in the Church of England are members of the House of Lords.

While most Americans remain religious, the fundamental belief that religion and politics should operate in separate spheres remains strong in the United States. A 2019 Pew Research Forum survey found that 63% of Americans thought that houses of worship should stay out of politics, while 76% of Americans agreed that houses of worship should not openly support political candidates.

Finally, clergy may be at a financial disadvantage when seeking a national political office. The majority of current members of Congress are millionaires. With the possible exception of some megachurch leaders, most members of the clergy do not enter their profession for financial reasons, and you won’t see many with the means to self-finance their campaigns.

Yet if Rev. Warnock were to win his election in January, it may signal a new trend. The U.S. House of Representatives currently has more ordained ministers than at any other time since occupational statistics began to be compiled in Congress in the 1950s. And if Rev. Warnock becomes a senator, it would be the first time in at least 55 years that the U.S. Senate has had two ordained ministers serving at the same time.

In the midst of a recession, a global pandemic, political polarization and climate change, perhaps more voters are looking for spiritual and moral leadership in Washington, D.C.

Robert Speel is an associate professor of political science at Penn State Behrend.