(RNS) — As we have remembered Martin Luther King Jr. and his contributions to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s each January, our memory of him has blurred to the point that it obscures much of his actual thought. In a seminal 2005 essay, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall wrote that King has been “endlessly reproduced and selectively quoted, his speeches retain their majesty yet lose their political bite.”

Specifically omitted from popular memory are some of the more “radical” elements of King’s message — democratic socialism, ending the war in Vietnam, nuclear de-escalation, a Poor People’s Campaign to force the federal government to address systemic poverty, and support of a sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis when he was killed.

For many, he has become the “quotable King,” his entire message reduced to his dream when his children would “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” In the same way, we have softened in our social memory how strongly many White evangelical Christians — even those deemed socially and politically “moderate” — opposed King.

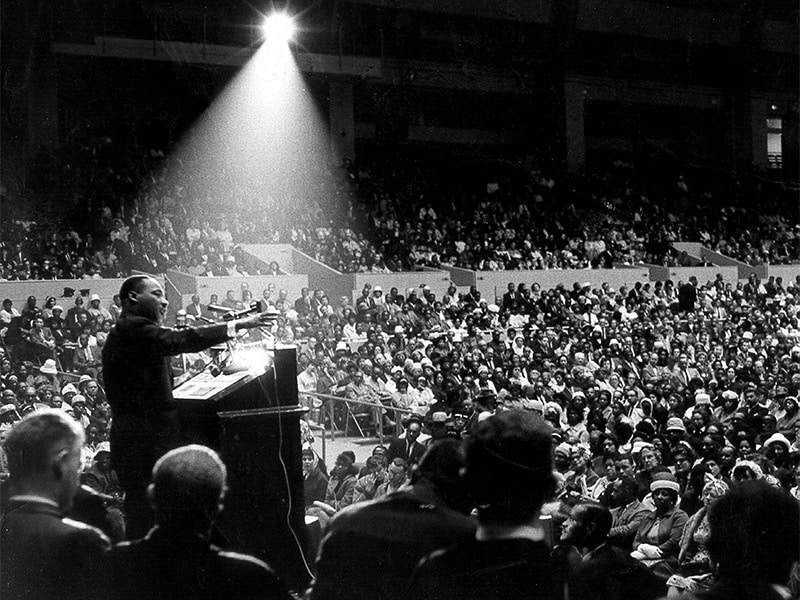

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at an interfaith civil rights rally at the Cow Palace in San Francisco on June 30, 1964. (George Conklin/Creative Commons)

King saw an indissoluble link between the Christian faith and the responsibility to change unjust laws and policies. But his emphasis on the social dimensions of Christianity, especially regarding race relations, angered many White evangelicals at the time. They considered race relations a purely social issue, not a spiritual one, and tended to believe that the government should not force people of different races to integrate. Some, of course, thought that racial segregation was a divine declaration and defended the practice from the Bible.

Decades after his death, White evangelicals finally came to recognize King’s contribution to American democracy and biblical justice. But during his lifetime, a large segment of the American church derided King and other activists and even resisted the aims of the civil rights movement.

The evangelist Billy Graham represented the moderate White evangelical position well. Christian commentators today make much of Graham’s gestures of support for Black civil rights, remembering the time, at one of his evangelistic crusades in 1953, when Graham personally removed the ropes dividing White and Black attendees. Four years later, he invited King to give the opening prayer at one of his rallies, an invitation that King accepted.

Yet as the civil rights movement continued and King led more demonstrations, Graham advised King and his allies to “put on the brakes.” Though Graham did more than many of his fellow Christian leaders, he never made any bold public proclamations of solidarity with Black citizens, and decided against demonstrating alongside activists on the March on Selma, a move Graham later said he regretted.

Like the White moderates King wrote about in his letter from jail, who paternalistically feel they can “set the timetable for another man’s freedom,” Graham never relented from the belief that “the evangelist is not primarily a social reformer, a temperance lecturer, or a moralizer. He is simply a kēryx, a proclaimer of the good news.”

While a resident of North Carolina, Graham claimed membership at First Baptist Church of Dallas, at the time, the largest congregation in the Southern Baptist Convention, and had great respect for the church’s pastor, W.A. Criswell.

Criswell was a magnetic preacher, but he had a dim view of the civil rights movement and of activists like King. When officials invited Criswell to preach at an evangelism conference for the South Carolina Baptist Convention in 1956, he called desegregation “a denial of all that we believe in.” He went on to say that Brown v. Board was “foolishness” and an “idiocy,” and he called anyone who advocated for racial integration “a bunch of infidels, dying from the neck up.”

Criswell moderated some of his stances later in life, but not before thousands of Christians in his own congregation and tens of thousands more of his followers nationwide had absorbed his views of civil rights and activists like King.

As time went on, efforts to give King a hearing in White evangelical forums were rejected. In 1961, King spoke at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the SBC’s flagship seminary, at the invitation of a professor. Powerful Southern Baptists opposed his visit.

As historian Taylor Branch wrote in his biography of King, “Within the church, this simple invitation was a racial and theological heresy, such that churches across the South rescinded their regular donations to the seminary.”

Even at his murder, some White evangelicals viewed King as an agitator whose presence they were glad to be rid of.

In his book Reconciliation Blues, writer Edward Gilbreath relates the experience of a Black college student named Dolphus Weary at a predominantly White Christian school in the late 1960s. Weary had received the offer of a spot on the basketball team through the persistent efforts of an admissions director.

Weary who was raised in rural Mississippi, attended Los Angeles Baptist College, now known as The Master’s University. Weary was one of the first two Black students at the school, and at first it was a positive experience. He earned good grades and helped lead the basketball team to a 19–5 record that season.

On April 4, 1968, a white classmate ran up to Weary and asked whether he had heard the news about Dr. King. Weary went back to his room and turned on the radio to get an update. He was “devastated” to hear that King had been shot. As he sat in his room he could hear his White peers down the hall, laughing. Then came the awful news that King was dead. As soon as commentators reported this news, the young Black man “could hear White voices down the hall let out a cheer.”

Reflecting back on this experience, Weary said, “Laughing at Dr. King’s death was just like laughing at me — or at the millions of other Blacks for whom King labored.”

Remarkably, Weary did not let the hate of others consume him. He has spent his life working for racial reconciliation in his home state, Mississippi.

The Gospel of John says, “A prophet has no honor in his own country.” We might extend it: A prophet (or truth-teller) has no honor in his or her own time.

If White evangelicals or anyone else wish to learn from MLK’s legacy, then they will ask who the modern-day prophets of racial justice are and whether they are willing to listen right now or will they honor the wisdom of these voices in the wilderness only after they die?

If White evangelicals or anyone else wish to learn from MLK’s legacy, then they will ask who the modern-day prophets of racial justice are and whether they are willing to listen right now or will they honor the wisdom of these voices in the wilderness only after they die?

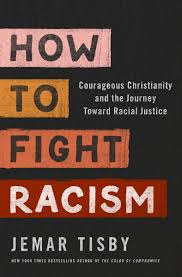

This article is adapted from Jemar Tisby’s How to Fight Racism: Courageous Christianity and the Journey toward Racial Justice. Follow him on Twitter: @JemarTisby.