As Dwight McKissic looks at the Southern Baptist Convention these days as a Black pastor in Texas, he sees a parallel with a scene in the new film One Night in Miami. The pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, Texas, talked about issues of racism and the SBC in the latest episode of the Word&Way podcast “Baptist Without An Adjective.”

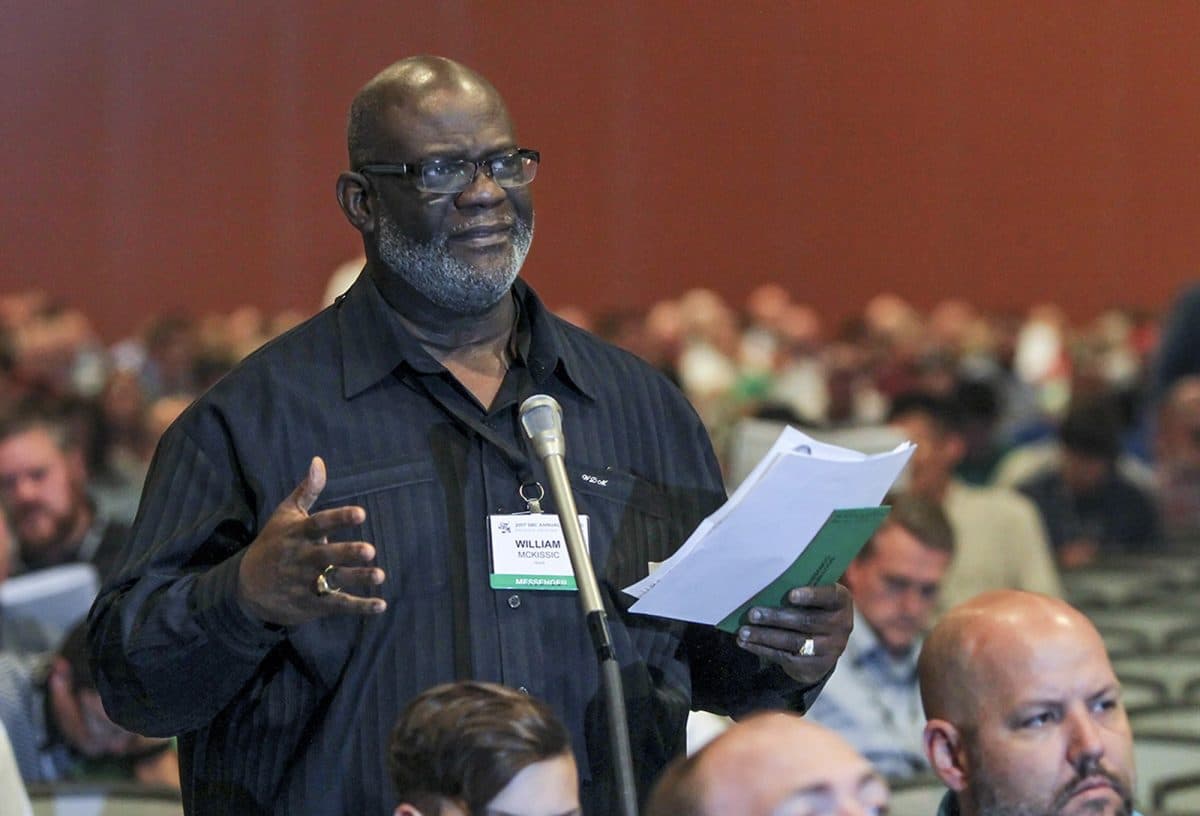

Dwight McKissic speaks about White Supremacy during the 2017 Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting. (Van Payne/Baptist Press)

McKissic successfully pushed the SBC to pass a resolution in 2016 repudiating the Confederate flag. And the next year he successfully pushed another resolution condemning White Supremacy and the alt-right movement.

But now he — like several other Black Southern Baptist pastors — feels dishonored. Just like a scene in that new movie.

One Night in Miami focuses on an evening in 1964 with Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Sam Cooke, and Malcom X after Ali defeats Sonny Liston to claim the world heavyweight champion title. Before these four Black men, each famous in their own area, gather together for the fight, the film first opens with each of them experiencing a struggle.

It’s the first scene with football great Brown — based on a true story in Brown’s autobiography — that caught McKissic’s attention as he watched the film.

Returning to his hometown in Georgia during the off-season, the NFL player is warmly greeted by a wealthy White family after he rings the bell on the door of their screened-in front porch. A young woman appears, and then bursts with excitement when he announces himself. She yells for her grandfather, who had requested the visit, and shakes Brown’s hand.

Returning to his hometown in Georgia during the off-season, the NFL player is warmly greeted by a wealthy White family after he rings the bell on the door of their screened-in front porch. A young woman appears, and then bursts with excitement when he announces himself. She yells for her grandfather, who had requested the visit, and shakes Brown’s hand.

The older man, referred to as “Mr. Carlton” by Brown, appears and with a smile declares, “Would you look at who’s on my porch!” He greets Brown with a handshake, and invites Brown to sit and talk. The two men chat while the young woman fetches lemonade for them. Carlton praises Brown’s skills on the football field, and pledges to help Brown in any way if ever needed. Brown, moved by Carlton’s support, relaxes a bit and notes that not everyone in the community is as supportive.

When Carlton’s granddaughter reminds him she needs help moving a piece of furniture, the young, athletic Brown stands up and offers to help.

“So considerate of you, Jimmy,” Carlton says, “but you know we don’t allow niggers in the house, so it’s quite alright. It really is wonderful to see you, son. You keep up the good work. You do us all proud.”

The man turns and walks off, leaving Brown standing on the front porch.

“They have a long front porch, a lot of chairs, a lot of places to rest food and plates and drinks,” McKissic said as he recounted that scene. “Sheltered, screened-in beautiful Southern front porch. Great visit out on the front porch. Access to the entirety of the front porches that sort of wrapped around the house. You’re welcome on the front porch, you can fellowship on the front porch, we can eat together, drink on the front porch, we can have great conversation on the front porch. But we don’t allow niggers inside our house.”

For McKissic, that moment symbolizes “kind of how I’m feeling about the SBC.”

“We’ll let you sit out on the front porch,” he said. “We’ll even let you preside out on the front porch, be president for a year or two on the front porch. But what we’re not going to do is let you make policy, is let you have a significant voice or any part of the conversation about race. We’re not going to include you as entity head. We’re not going to let you inside the house. And we’re not going let you move the furniture around in the house. We could just only enjoy your smile with you on the front porch.”

In January, McKissic announced his church would leave the Southern Baptists of Texas Convention after the SBC-affiliated group passed a resolution condemning Critical Race Theory, a decades-old broad social science perspective that scholars use in analyzing issues of race, power, and society. The resolution denounced CRT as “secular” and “an unbiblical approach to the problem of sin that brings division among ethnic diversity and, as such, must be rejected.”

And McKissic said his church will leave the SBC if that body makes a similar move at its annual meeting in June. In November, the presidents of the six SBC seminaries — all Anglo men — issued a statement condemning CRT. Leaders of the SBC’s National African American Fellowship criticized the statement. And Black Southern Baptist pastors from Minnesota to Illinois to Kentucky to Texas and elsewhere said they were leaving the SBC after the anti-CRT move.

As the controversy grew, the seminary presidents held a virtual meeting with several Black Southern Baptists on Jan. 6. While the presidents admitted they should’ve discussed the matter with the Black pastors before the anti-CRT statement, they also said it wouldn’t have changed their statement. McKissic attended the Jan. 6 session, which he discusses in the “Baptist Without An Adjective” episode.

For McKissic, the anti-CRT moves cannot be ignored.

“I cannot betray the history of my people by remaining in a convention that would make these kinds of decisions in 2020 without even really caring what we thought, and when they hear it doesn’t change them at all,” he said. “I’m not going to desecrate the graves of Frederick Douglass and Benjamin Banneker, W.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Phillis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman … Martin Luther King.”

“I’m not going to desecrate their graves,” he added, “and participate in a system that would leave us on the front porch.”

NOTE: Hear more about this topic and much more from McKissic in the latest episode of Word&Way’s award-winning podcast “Baptist Without An Adjective.”

NOTE: Hear more about this topic and much more from McKissic in the latest episode of Word&Way’s award-winning podcast “Baptist Without An Adjective.”