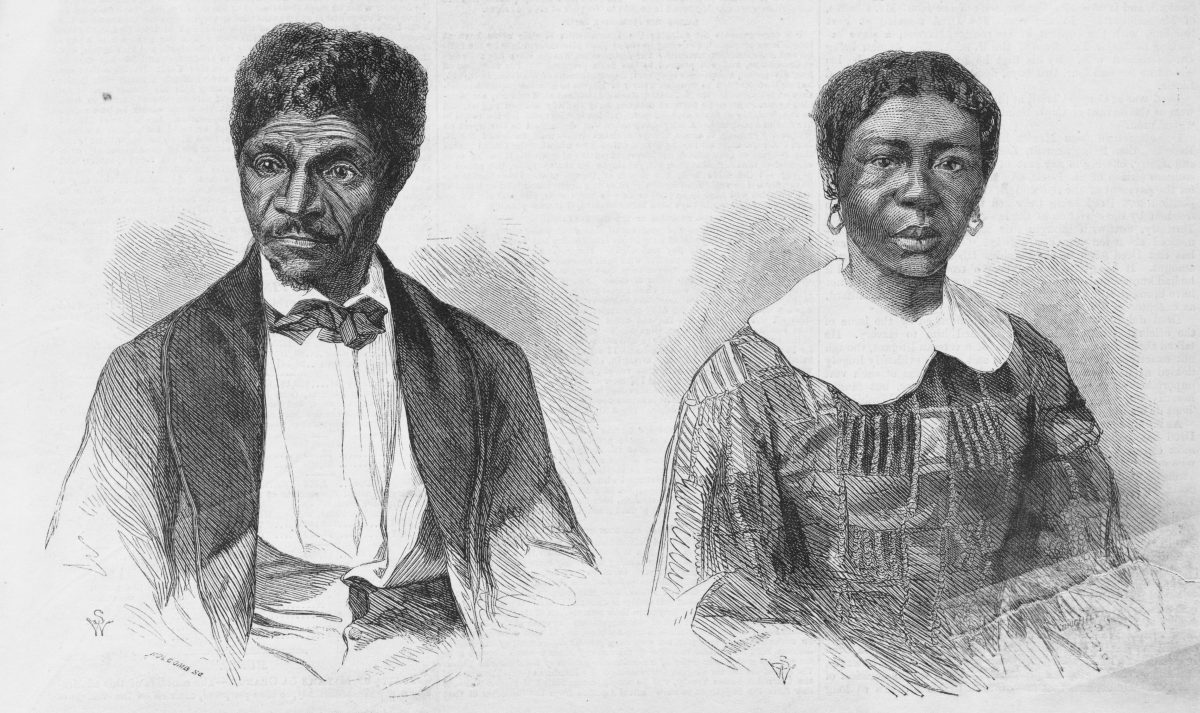

Dred and Harriet Scott wood engravings after photographs by John H. Fitzgibbon.

That changed when their case reached the Missouri Supreme Court. With three members elected by popular vote for the first time in the state’s history and growing national agitation over slavery, the court, in a 2-1 decision, overturned all standing precedent and returned the couple to bondage.

“Times now are not as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made,” Judge William Scott wrote in the majority opinion.

That decision set the stage for one of the most racist decisions ever by the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1857, ruling on an appeal of a federal court decision against Dred Scott’s petition, Chief Justice Robert Taney ignored precedent and history to not only deny Scott his freedom but strip all Black Americans, free or slave, of their right to sue in federal courts because they were not citizens.

Now, 164 years later, a resolution heard Tuesday (Feb. 9) in the Missouri Senate Rules, Joint Rules, Resolutions, and Ethics Committee states “that the times have once again changed and we declare the March 22, 1852, Missouri Supreme Court Dred Scott decision is fully and entirely renounced.”

State Sen. Steve Roberts, D-St. Louis, told the committee that the bicentennial of Missouri’s statehood is the time to make a statement denouncing the decision and Missouri’s history of slavery.

The resolution “renounces the Missouri Supreme Court decision and affirms that we, as Missourians, will forever affirm that all people are created equal,” Roberts said during Tuesday’s hearing.

The committee took no vote on Roberts’ resolution.

A similar resolution passed the Missouri House in 2018 but did not receive a Senate vote, Roberts reminded the committee. Last year, it received favorable hearings early in the session but the COVID-19 pandemic derailed most legislation.

And to remind senators that actions with little actual impact can still have a symbolic importance, Lois Hogan of the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation noted that it was not until 1975 that then-Gov. Kit Bond issued an executive order rescinding Gov. Lilburn Boggs’ 1838 order that Mormons “must be exterminated or driven from the state.”

“What we want to do here is clear up this blight that should have never been,” Hogan said.

Missouri was born in controversy over slavery.

First, to gain admission, Congress had to agree to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which prohibited slavery in most of the territory in the Louisiana Purchase. Then, when Congress was debating the proposed state Constitution, it insisted on removal of a clause barring free Blacks from settling in the state.

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia about 1799 and sold to an army physician, John Emerson, in 1830 in St. Louis. Emerson moved frequently for his army postings, first to Illinois, then to a frontier outpost of Fort Snelling in what is today Minnesota. It was at Fort Snelling that Dred Scott met and married Harriet Robinson.

Slavery was banned in Illinois under the 1787 Northwest Ordinance and in the area around Fort Snelling by Missouri compromise. After Emerson retired from the army, he returned, with Dred and Harriet Scott, to St. Louis. In their court cases, the Scotts argued that they became free when they were transported to a free state. And until their case came before the Missouri Supreme Court, it was settled precedent in the state that they were right.

“These decisions, which come down to the year 1837 seem to have so fully settled the question, that since that time there has been no case bringing it before the court for any reconsideration until the present,” Judge Hamilton Gamble noted in his dissenting opinion.

The decisions that returned the Scotts to slavery are a shameful episode and the resolution is a chance to show the state regrets that era, Roberts said in an interview Monday.

“My goal is that we have never, from a legislative standpoint, condemned that decision,” Roberts said. “It is a blight and a shame on our state.”

Roberts, who is also sponsoring several bills designed to reform policing in the state, including a limitation on chokeholds, said the resolution is a step forward in repairing race relations.

“There is meaning in symbolism,” Roberts said. “It is not a bill that is going to change how crimes are prosecuted in the state, but it sends a message.”

Scott did not remain a slave after the U.S. Supreme Court decision, but his second period of freedom did not last as long as the first. Calvin Chaffee, the second husband of Irene Emerson and an abolitionist Congressman from Massachusetts, arranged for his and Harriet’s emancipation on May 26, 1857.

Dred Scott remained free until his death in September 1858. Harriett Scott lived long enough to see all other slaves in the state freed when Missouri passed emancipation on Jan. 11, 1865. She died in 1876.

This piece was originally published by Missouri Independent, and written by Rudi Keller. Missouri Independent is part of States Newsroom, a network of news outlets supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Missouri Independent maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jason Hancock for questions: info@missouriindependent.com. Follow Missouri Independent on Facebook and Twitter.