TULSA, Okla. (BP) – A hundred years after a horrific massacre, Deron Spoo hopes to set the foundation for a new narrative. The senior pastor of Tulsa’s First Baptist has studied the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, in which as many as 300 Blacks were killed and 35 blocks of Black-owned homes and businesses were reduced to ashes over a two-day period.

First Baptist was among White congregations that helped house more than 10,000 displaced Black residents. But in the Sundays following the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, comments from pastors of those same churches were not indicative of the aid extended.

“There were newspaper articles that share what those pastors said the following Sundays in their pulpits, and it was not good,” Spoo said. “It was offensive, it was racist, and those are a matter of public record.”

The Tulsa Race Massacre Prayer Room at First Baptist Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma. (FBC Tulsa/Baptist Press)

His answer: the informative and inspirational Tulsa Race Massacre Prayer Room for the church and community.

“First Baptist Tulsa, we were located on the same spot 100 years ago. We opened a room for the healing of the refugees, those who were wounded and needed a place to stay. The church offered refuge,” Spoo said. “It just kind of dawned on me and some of our leadership 100 years later, ‘Why don’t we open another room for healing, and why don’t we have a prayer room and pray for the healing of the wounds of racism that still exists in our world today?’”

The room, open February through June 1, will offer a space for 121 days of intensive prayer as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission holds months of events in advance of the official June 1 centennial commemoration.

“I think it’s important for our church to be a part of this project to send a message into the future, but also for today,” Spoo said, “that racism doesn’t have a place in the heart of the church, nor in any follower of Jesus.”

Fellow Southern Baptist pastor LeRon West, who leads Tulsa’s predominantly-Black Gilcrease Hills Baptist Church, thinks the prayer room could foster reconciliation in Tulsa, which he describes as still divided.

“To have a place where different people can come in and pray, and pray together … that goes a long way, because relationships happen as we’re in the proximity of one another and begin to see each other that way,” West said. “And the church has to lead out in that. If the church is divided, the world has no chance.”

The Greenwood community holds special prominence for West. His late grandfather bought a restaurant in the community in 1928 as Blacks rebuilt after the riots, and West worked in the restaurant as a youth. The 35-block area of north Tulsa known as Black Wall Street rebounded through the 1950s, later suffered decline and, according to historian Hannibal Johnson, is experiencing a renaissance as a business, educational, and cultural hub.

“It was extremely segregated,” West said. “Tulsa is still divided.”

While Tulsa is actively discussing racial reconciliation as the centennial approaches, Spoo believes only God can change human hearts in a way that will unite the community.

“We can solve a lot of problems if we communicate together, but I think we can solve more problems if we communicate with God,” Spoo said. “So while we’re talking about this, why don’t we include God in the conversation?”

First Baptist Tulsa worked with the Tulsa Historical Society in establishing the prayer room that Spoo describes as museum quality. Sections include historical accounts and images, newspaper reports, written prayers and prayer points, four prayer stations with audio guidance, and a joint anti-racism statement signed by Spoo and fellow pastors of downtown churches.

“I ask people to stop and pray against the spirit and sin of racism in our culture and against the spirit and sin of racism in the church, and in our particular church, and then the spirit and sin of racism in our lives,” Spoo said. “The only person who can change the human heart is God. I might not be able to change the culture of Tulsa, but I sure am responsible for changing my heart and making sure it is right before God and loving toward other people.”

“I just think it’s important for posterity to have First Baptist Tulsa’s name on that, to say we’re a part of this,” Spoo added. “We can’t change what happened in 1921, but we certainly do have a say in what happens in 2021.”Spoo has enlisted at least one church member a day to pray in the room, preferably at 12:21 p.m., following a narrated self-guided tour that takes 20-30 minutes. Community members are also free to visit the room, and community groups are encouraged to tour. At the end, participants are encouraged to learn about the massacre’s survivors, and to make a donation to the Greenwood Rising history center, with First Baptist Tulsa committed to matching up to $5,000 in contributions for a potential $10,000 gift. Names of supporting organizations will be preserved on bricks or plaques at the center.

The community’s response has been overwhelmingly positive, Spoo said, although a small minority has decried the room and also disparaged the commemoration.

Spoo collaborated with Philip Armstrong, the centennial commission project manager and a minister at Metropolitan Baptist Church in Tulsa, a National Baptist Convention USA-affiliated congregation. Armstrong narrated the guided prayer stations at First Baptist Tulsa.

“At the heart of it all, we are God’s creation. And we are still dealing with this horrible sin called racism even 100 years later,” Armstrong said. “And it’s kind of like the cries of Blacks and Whites, young and old over this past summer with George Floyd’s death, ‘Enough is enough.’”

(Baptist Press)

“Tulsa, because of its history, is now being the place where people are saying it’s ground zero, ground zero of race relations, ground zero of racial trauma, and a place where people can maybe find a way to get on this journey to reconciliation,” Armstrong added.

Armstrong is readying for the June 2 dedication of the new multimillion-dollar Greenwood Rising history center at the entrance to the historic Greenwood community. He believes the prayer room is an important outreach for the church in the 121 days leading up to the dedication, as it can cause many to face historical facts.

“Especially for a largely White congregation and places and organizations … like that, it causes them to step back and say, ‘We can no longer continue to tell people let’s not talk about that, it happened in the past. Let’s just move on,’” Armstrong said of the prayer room. “It makes people stop and face the fact that maybe because we’ve done that for so many years is why we’re still dealing with racial division. It’s because all we want to do is sweep it under the rug.”

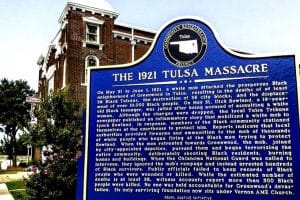

According to a historical marker to be dedicated in the Greenwood community, Black Tulsans went to the courthouse to protect a prisoner the White community planned to lynch on May 31, 1921. The prisoner, 19-year-old Dick Rowland, had been accused of assaulting a White woman on an elevator, although the charges were later dropped.

The marker cites reports of authorities providing firearms and ammunition to the mob of thousands of White men who fired upon Black men, forcing them to retreat towards Greenwood. The White mob followed, and joined by city-appointed deputies, began shooting Blacks and burning homes and businesses. The Oklahoma National Guard arrived and instead of stopping the violence, arrested hundreds of Black men. No one was ever held accountable for the destruction and death, the marker records.

Death counts are not certain, but they range from official accounts of 36 to eyewitness accounts of more than 300. All that remains of the original Greenwood, dubbed Black Wall Street, is under the foundation of Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was rebuilt after the massacre.

“You cannot move beyond the injury,” Armstrong said, “until that injury has been addressed. … We need people of faith to stand up and say this was wrong, it was horrific … but here we are 100 years later. Let’s not make that same mistake. Let’s not sit on the sidelines.”

West has also collaborated with Armstrong and fellow Tulsa pastors in planning faith-based events to mark the centennial, although he regrets having to commemorate a tragedy.

“It would be my hope that after this commemoration, that there are more relationships built across racial lines, across religious lines, across political lines, that we genuinely care about each other in a way that we need to,” West said. “In the times that we need each other, what does race matter?”