“We’ll fling our Green and Gold afar,

To light the ways of time.

And guide us as we onward go.

That good old Baylor Line.”

So ends the official school song of Baylor University, an institution that means so much to me. As a fourth-generation alum (B.A., 1995), Baylor holds a special place in my life. My formative years there shaped my faith, character, and outlook as much or more than any period in my life. Lifelong friends and a kindred spirit with other Baylor Bears ripple throughout my journey. I continue to “fling” my Baylor experience wherever I am in hopes that my heritage and my future are enlightening the ways of my time on this earth and the call of God on my life.

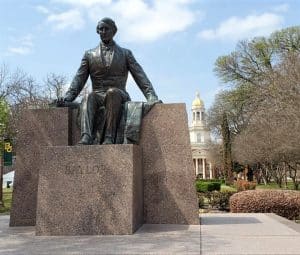

Statue of Judge R.E.B. Baylor on the campus of Baylor University. (Patrick Wilson)

This past week, while traveling from our home in Missouri to Texas, I had a few brief hours to spend on the Baylor campus. I reminisced as I passed through Penland Hall (where I lived as a freshman and served as a resident assistant my sophomore and junior years), peeked in on Joy and Lady (the two bears that serve as Baylor’s mascots), and walked through the Burleson Quadrangle (where many of my classes were held). I relished the historic buildings of my time at Baylor, while also appreciating the continued developments around campus. I stopped to take a picture in front of Pat Neff Hall and next to the central statue of the university’s namesake, Judge R.E.B. Baylor.

Yet, this stroll down memory lane was filled with new emotions. Continued Baylor spirit and pride coursed through me, but they were marred by a new sensitivity to the culture of 1845 and the prevalence of slavery and inequality rampant among the South and very much a part of the origin of my alma mater.

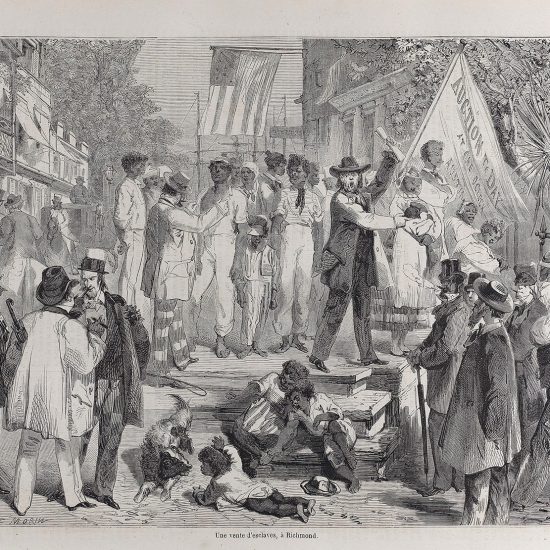

Just hours before my sojourn across Baylor, the report from the Commission on Historic Campus Representations was released to the public. Back in June of 2020, the Baylor Board of Regents established the commission to investigate and report on the university’s historical connections to slavery and the Confederacy. Refusing to take the lazy and uniformed approach of either dismissing the university’s ties to these sinful and unbenevolent activities of our nation’s past or hastily acting to undermine the long-standing heritage of the university, the commission did the hard work of reading, listening, learning, and sharing through difficult conversations that resulted in greater understanding and consensus building.

Commission Co-Chairs, Alicia Monroe, Gary Mortenson, and Walter Abercrombie stated their mission: “We believe now is the time for Baylor, as a Christian university, to lead by listening and learning with humility about our past and from voices that have been unheard for years while also taking tangible steps forward. In addition to making an important and visible contribution to today’s campus and Baylor community, the Commission’s work will create a lasting legacy for future generations of Baylor Bears.” Guided by the biblical mandate to love both God and neighbor (Matthew 22:37-39), the commission established principles to evaluate the historical data with honesty, dignity, love, redemption, and hope.

In the 94-page report, the commission analyzed each monument on the Baylor campus and the ties of the historic founders of Baylor to the practice of slavery and the Confederacy during the Civil War. Historical information was explained, monuments pictured, inscriptions evaluated, and recommendations clearly presented for consideration by the Board of Regents and the university administration.

Instead of saying that all monuments on the campus needed to be treated in the same manner, the commission provided individualized recommendations. These recommendations included erecting statues to Baylor’s first African American graduates and a new monument to the “unknown enslaved” who built Baylor’s campus in Independence.

While the commission did not affirm a change of name to the university, it recognized Judge Baylor as a slave owner and recommended changes to the inscription on his monument. Due to Burleson’s derogatory speech about slaves, personal involvement in the Confederate army, and promotion of the “Lost Cause,” the “quad” bearing his name was suggested to be renamed and his statue moved to a less prominent location. Other recommendations made by the commission included additional actions such as the building of a commemorative tile walkway, relocation of bells and other statues, renaming of some buildings, retiring the current mace used in commencement, and replacing Judge Baylor’s likeness on the Founder’s Medal.

As a Baylor alumnus, whose family has been enrolled or in advocacy of the university for much of the last century, I am grateful for the thorough and diligent work of the Commission on Historic Campus Representations. Such an endeavor is filled with much scrutiny and degradation from opponents on all sides. It would be much easier to simply overlook and justify Baylor’s original founders as being products of their cultural environment. Yet, the commission was willing to do the honest and comprehensive work to admit the historic ties to slavery and inequality — to seek to shine into the darkness of our past and “to light the ways of time.”

My personal awakening to racial inequality and the need to grow into becoming an anti-racist was birthed in the merciless death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. I have spent much of the past year doing a similar work to that done by my alma mater — reading, learning, understanding, reflecting, confessing, repenting, and seeking ways to personally grow and effect a greater racial equality in the lives of others around me. The “light” of Christ continues to shine in me, exposing sinful attitudes, patterns, and behaviors that need to be replaced by the redemptive work of a gracious God (John 3:20).

I commend the work of Baylor University to cultivate an ever-growing and self-reflective environment where the mistakes of the past are brought to light, where change is embraced, and where all people are welcomed with the acceptance, grace, and love of Jesus. I am horrified and ashamed of the inhumane actions of many that laid the foundation for Baylor, including Judge Baylor, himself. Yet, I am proud to be a part of an institutional family that is willing to take the humble road to recommend changes.

While we can never truly “right the wrongs” of our past, we can prevent them from continuing to plague our future. I pray that through intentional effort both in my own life and in the future endeavors of universities, businesses, churches, and other institutions across America, we can seek to be better and to do better.

Over 175 years ago, Baylor set out to be a place that is “fully susceptible of enlargement and development to meet the needs of all ages to come.” Once again, Baylor is charting a course forward that is neither easy or painless. Yet, through the reflective and introspective evaluation of our past, we can look forward to a brighter future where all are welcomed, accepted, and treated with Christ-like kindness. We can no longer afford to stand on the sidelines and long for a world of equality; we must do the hard work, both personally and collectively, to end systemic racism and unite America as “one nation.”

I pray that Baylor will strive to be a Christ-centered people, who will not seek to create a “line” that separates people as superior and inferior. Rather this “Baylor Line” will be a line of every tribe, nation, and tongue, in which all people stand side-by-side in equality, united it heart and spirit, committed to the same mission: “to light the ways of time.” Dear God, please “guide us as we onward go!”

Patrick Wilson is senior pastor at Salem Avenue Baptist Church in Rolla, Missouri. He is a graduate of Baylor University, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Logsdon Seminary.