There is a genre of Christian books that attempt something audacious. They try to concisely explain the major claims of the faith in an accessible way. This stands in contrast to the self-help emphasis of many books on “the Christian life” that you’ll find in bookstores or the dense academic treatises on theology written by scholars intent on talking mostly among themselves.

The classic volume in this category is C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, which originated as lectures shared on the radio during World War II. There is a new entrant into this small club: Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt’s The Love that is God (Eerdmans, 2020). Born out of a sermon that sought to convey the basic meaning of Christianity today, this book offers an invitation to new and long-time followers of Jesus to reflect on the faith we profess.

The classic volume in this category is C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, which originated as lectures shared on the radio during World War II. There is a new entrant into this small club: Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt’s The Love that is God (Eerdmans, 2020). Born out of a sermon that sought to convey the basic meaning of Christianity today, this book offers an invitation to new and long-time followers of Jesus to reflect on the faith we profess.

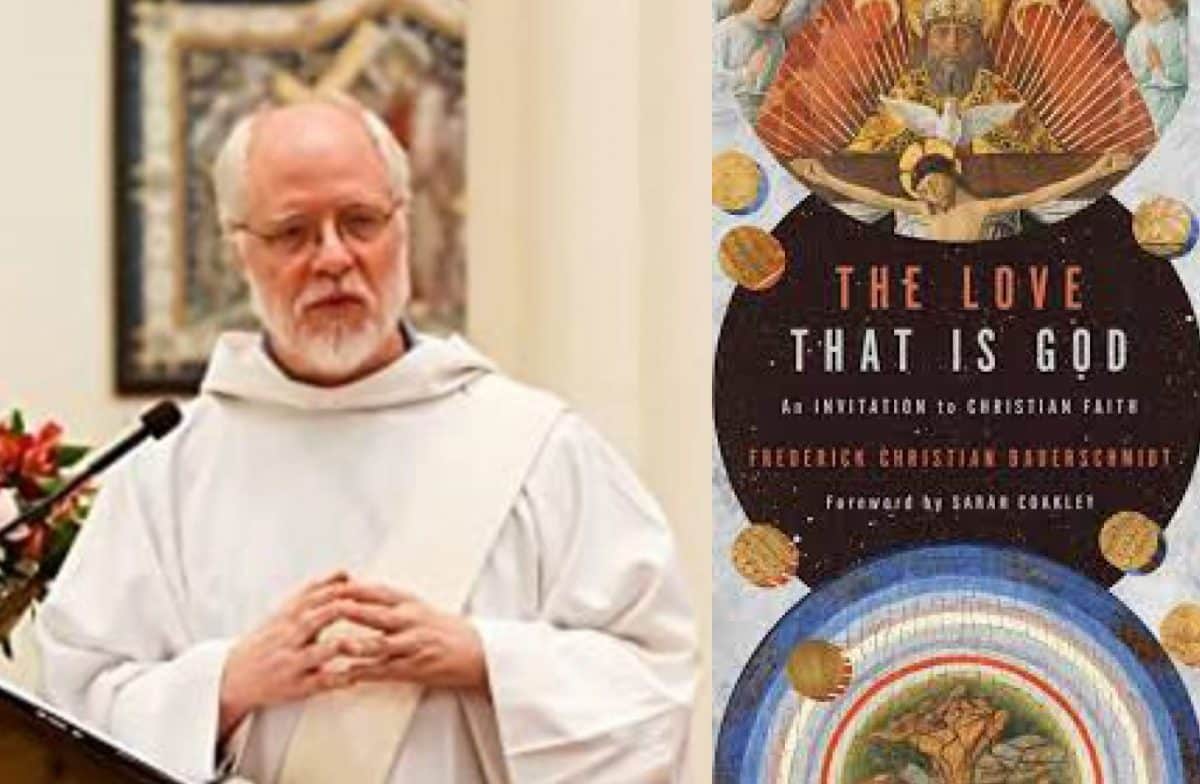

We recently interviewed Dr. Bauerschmidt — who teaches theology at Loyola University Maryland — by e-mail about his reasons for writing, the book’s main message, and why “love” is not a sentimental idea but central to what Christians believe about God.

Who do you hope reads The Love that is God? What would you anticipate readers of various religious perspectives to find in it?

As your question suggests, I hope it would be helpful to both outsiders and insiders to Christianity. For an outsider to Christianity, I would hope that they would discover that the Christian faith actually has something to offer: a story to tell that can give life’s questions a larger, more hopeful framework; practices that can enrich and sustain a yearning for meaning; a community that can provide companionship on the adventure of existence. Even if they were not moved to become a Christian, I would hope that they might develop a deeper understanding of why someone else might to be one.

For the insider, I would hope that they might be reminded of why they are a Christian and be encouraged in their faith. I also hope that Christians would be challenged to think in new ways about God, Jesus, and the Church, so as to live their faith more deeply and to bear more effective witness to the Gospel.

You write that “trivialization [of love] can lead us to forget that the claim that God is love is the radical claim of Christianity.” What do you mean by this and how do Christians rediscover it?

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt

I suppose I mean that the belief that God is love is both at the root of all our beliefs (which is where the word “radical” comes from) and that it is a belief with revolutionary consequences for our personal and interpersonal lives, as well as for the world.

As to how we rediscover this, the method I employ in the book is to try and place our everyday lives into the scriptural story, as interpreted through the lives of exemplary Christians of the past — those whom my tradition refers to as “saints.” That is one reason why the book engages Christians ranging from great theologians like Augustine and Aquinas to activists like Martin Luther King Jr. and Dorothy Day. I think that reflecting on how people have embodied the revolutionary belief that God is love in their times and contexts can spark our imaginations as to how we might embody this in our own time and context.

“We might say,” you write, “that love is the desire for and delight in someone or something’s goodness.” If “God is love” then can we define God as “the One who desires for and delights in our — and the world’s — goodness?” Is there anything that definition leaves out about God?

I think this definition leaves out how God has, down through the centuries, desired and delighted in the world’s goodness. To be a Christian is not simply to believe that God is love; it is to believe that God has loved the world in a particular way: through making a covenant with Abraham and his descendants, through taking on crucified flesh in Jesus of Nazareth, through pouring out the Spirit on Jesus’s followers to make of them a single living body. The word “love” is interpreted for us through the particulars of this story, which helps prevent the claim that God is love from being turned into a sentimental (and infinitely malleable) platitude.

You want readers to understand the crucifixion as an expression of Jesus’s obedience to the Kingdom of God, and the love it reveals, rather than divine punishment for human sin. What do atonement theories of the cross miss?

While it is true that the cross stands at the center of the story of Jesus, it cannot really be understood in isolation from what precedes and follows it, namely the life of Jesus and his resurrection. If it is isolated from these it can be reduced to some sort of mechanism for balancing the scales of divine justice, a justice understood as something independent from God’s loving will. It also obscures the role that we human beings play in the killing of Jesus, a role that reveals just how threatened we are by the kind of kingdom Jesus proclaims.

Some reviewers of the book have seen me as hostile to substitutionary accounts of atonement. I don’t think this is the case. I am a big fan of Anselm’s account of satisfaction, particularly as tweaked by Aquinas to highlight the cross as an offering of love and obedience made by Jesus to the Father on our behalf. What I am critical of is the notion that, on the cross, Jesus suffers the divine punishment that is due to us. This seems to me to run counter to the understanding of God that is conveyed by Jesus’s teachings, making God both unloving and unjust.

We live in a hyper-individualistic culture, where my demands take priority over the welfare of the community. Many Christians have adopted this attitude uncritically. They shop for churches reflecting their preferences and expect their needs to be catered to by their congregation. You push back strongly against this mindset. Why do Christians need to invest themselves in community? How does the Church help us see the love that is God?

Well, some days the Church seems largely to obscure the love that is God; therefore people walk away from it. But at its heart the Church is Christ’s body in the world and the temple of his Spirit. I do not think the failures of the Church can take that away, since that identity is produced by God’s grace, not by our moral achievement.

One thing I emphasize in the book — and this might reflect my own Catholic tradition — is how the practices of the Church, such as baptism and the Eucharist or Lord’s Supper, contain within themselves the revolutionary potential of divine love, a potential that is there no matter how mediocre the Church might be. If you really think about the meaning of these practices, the death and rebirth of the self that is promised in baptism, the presence of divine crucified love in the Eucharist, they impel us to embrace the God who is love. And these are practices that need a community in order to be carried out: you can’t baptize yourself; you can’t give yourself communion. Though we want these practices to cohere with the other practices of our churches, even a community that has grown lukewarm in its faith still contains within it the seeds of the revolutionary Gospel Jesus proclaimed.

I also think that we all need concrete experiences of Christian community in which the words of Scripture and the tradition are heard by a diversity of ears and spoken in a multitude of voices. The diversity of gifts and experiences that one finds in even the most outwardly homogeneous congregation can help to remind us that the love that is God is too big to be captured by one person’s perspective.

You identify that “Christian teaching on forgiveness and love of enemies is in some ways both the most attractive aspect of Christianity and the most repellent.” For Christians, are there any boundaries on forgiveness? Does Jesus really want us to love those who hate us?

It seems to me that the connection between our forgiveness of others and our forgiveness by God is a red thread that runs throughout the entire New Testament, in both the Gospels and in Paul’s letters. We must love our enemies because, when we were God’s enemies, God still loved us. Even when we crucified God, God still loved us. And if we are, as Jesus says, to be perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect, then this kind of love must at least be our target.

Particularly in our day, when social media has given is a way to hate our opponents from a safe distance, the call to love our enemies has emerged as one of the most counter-cultural of Jesus’s teachings. I have even encountered people who suggest that the love of enemies that Jesus commands is something positively immoral. Of course, the early Christians were also often accused of immorality by the Romans, so you are in good company.

Your comment that “faith in God … something upon which we stake our lives” is quite revealing. This is clearly more than an academic exercise for you. Why do you stake your life on the God who is love? What would you encourage others (who aren’t professional theologians) to do so they might take ownership of their faith in the same way?

I sometimes ask myself why I am a Christian; it seems to me that there is no single clear reason, but rather a convergence of intuitions, arguments, contingent circumstances, and personal relationships that together have landed me where I am. But at the heart of it all is a conviction that the love that is revealed in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth is what holds the key to the mystery of existence, that thing that some of us call “God.” I have tried to live my life in such a way that, if this conviction is false, then my life is absurd, and probably deserves widespread mockery.

I wrote the first draft of this book very quickly — in about three weeks — and found myself reflecting on how the speed with which it flowed forth from me was not only a function of the years I had spent teaching theology, but also a sign that, well, I actually do believe this stuff.

Those who do not have the blessing/curse of being professional theologians are still called to think and speak about the things of God. And all of us are called to do that in community, so that our thoughts and words might be tested in the crucible of our common experience of God. I would say that speaking and listening to each other in the Christian community challenges us to own the faith we profess as our contribution to the common faith of the Church. It also challenges us to let that faith be challenged and expanded by the faith of others.

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt, a professor of theology at Loyola University Maryland, is the author of The Love that is God (Eerdmans, 2020). Interviewer Beau Underwood is senior editor for Word&Way.