“Pray without ceasing,” the Apostle Paul exhorts Christians in the early church (1 Thessalonians 5:16). The spiritual life is one of constant interaction with God. But what does this look like in practice? What does it mean to pray without ceasing in the world today?

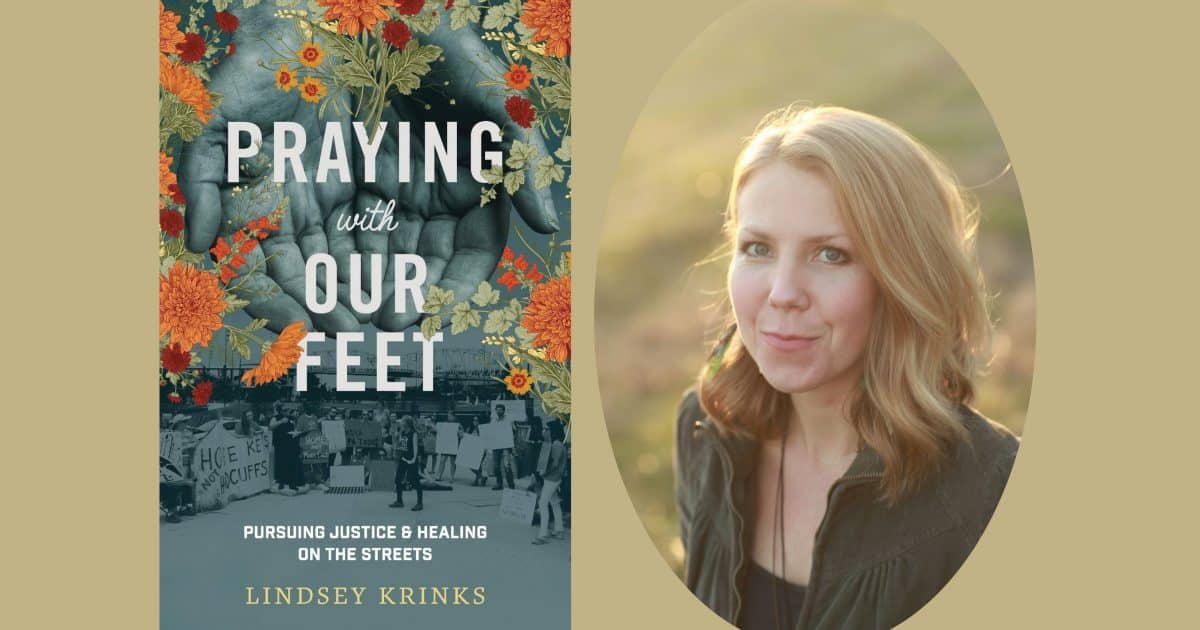

Lindsay Krinks

Lindsey Krinks, a street chaplain and social justice activist in Nashville, Tennessee, offers one compelling answer. Her prayers are not restricted to words of petition. They are visibly expressed in moments of solidarity, acts of compassion, and advocacy for social change with and among the unhoused in Tennessee’s state capital.

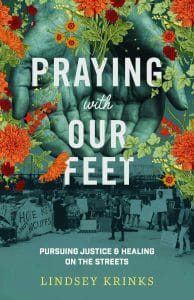

Krinks details her calling and ministry in a new book, Praying with Our Feet: Pursuing Justice and Healing on the Streets (Brazos, 2021). Her writing warrants your careful attention and promises to stir your soul.

The book is an inspiring memoir of a young, arguably naïve, Christian becoming awakened to the inequities of the world through seeing the injustices of her local community. Rudely confronted by the powers that protect and perpetuate these societal sins, she is transformed from a well-intentioned but inexperienced college student into a committed, strategic activist. Realizing that “kindness lived out on a systemic level is justice,” she focuses her attention and energies to realizing this ideal in service to and in collaboration with those whom our society neglects but Jesus would never forget.

Her memoir also describes her own theological and vocational journey. Raised in a conservative church tradition that denied women the chance to fully participate in leadership, especially professional ministry, Krinks wrestles with the way her upbringing continues to perniciously affect her current sense of ministry.

“I had internalized the message that I shouldn’t speak up,” she writes about her childhood impressions of gender roles.

Yet, she finds herself serving God’s people in ways that require her voice and, eventually, are recognized as ordained ministry.

Additionally, the book is a gentle and valuable introduction to issues of homelessness, housing insecurity, and interconnected policy issues and socioeconomic factors. Without diving into wonky dynamics, she introduces readers to the difficulties of landlords and substandard housing, of the intersection of mental health conditions and chronic homelessness, and the various ways the structures of our society do not work for those on its margins.

You cannot digest the stories on its pages without becoming righteously indignant over the episodes she describes. Still, her intention is not to offer a cure for these social ills. Rather, she humanizes what we often perceive as abstract problems and insists that followers of Jesus have a responsibility to care about the people, and their particular stories, involved.

Krinks seeks to be a prophetic witness to what has gone wrong rather than claiming an expertise in how to make it right. Above all, she insists we see these challenges from a particular perspective. As Christians, we first need to grasp the realities of the street instead of privileging the perspectives of those in power.

Within her story there is a thread of disappointment. The institutional church is an obstacle or problem as much as it is a solution. Government leaders say the right things but follow through with half measures. The people she’s ministering to frequently encounter new problems or prove unable to get their proverbial houses in order. Her colleagues find the work unsustainable and burn out.

All hope, however, is not lost because, as she writes, “we keep believing, against all odds, that another world is not only possible but that it is on its way.”

Perhaps the book’s most valuable contribution to its readers is the way she struggles with these letdowns and her own limitations. She writes of being “trapped in the tension between telling myself that the responsibility for others didn’t rest solely on my shoulders and knowing that many situations depended on my response.” Eventually she is able to differentiate being responsible “for” someone — having to carry them along — and being responsible “to” someone as steadfastly walking beside them. This is a lesson every advocate, pastor, social worker, and compassionate human being needs to learn.

The only thing better than reading this book alone would be the chance to discuss it with others. Praying with Our Feet is the inaugural selection in the Word&Way Book Club. Each month a different title will be announced for those interested to purchase from their favorite bookseller. Then, Word&Way will host facilitated small group discussions for those wanting to digest the book in community. You can learn more and sign up for one of the meetings in June by visiting wordandway.org/bookclub.

The only thing better than reading this book alone would be the chance to discuss it with others. Praying with Our Feet is the inaugural selection in the Word&Way Book Club. Each month a different title will be announced for those interested to purchase from their favorite bookseller. Then, Word&Way will host facilitated small group discussions for those wanting to digest the book in community. You can learn more and sign up for one of the meetings in June by visiting wordandway.org/bookclub.