Donald W. Dayton, who died last May 2020 at age 77 in California, was an important interpreter of Evangelical, Wesleyan, Holiness, and Pentecostal traditions, revealing how they were connected and displaying how their roots were more entangled than historians had previously understood.

Donald W. Dayton (Christian T. Collins Winn)

Dayton was the first book editor at Sojourners (previously Post American) in 1975 as that community moved from the Chicago area to Washington, D.C. Don was not merely a bridge builder, but often served as the bridge himself. He bridged Pentecostal and Wesleyan traditions to Evangelical and Reformed traditions, social justice reform traditions to orthodox Christian traditions, ecumenical organizations to lesser known holiness movements, Western European Christian movements to Asian Christian movements. He left behind legacies including his many students (he advised scores of Drew Theological Seminary students among others at North Park Theological, Northern Baptist, Fuller, and international seminaries), his son Soren, friends, and colleagues across the country and around the world.

Having persevered through significant life challenges alongside his regular intellectual sparing matches, his efforts bore fruit and service to the church and humanity, benefiting a range of organizations and networks from the World Council of Churches, Wesleyan Theological Studies, The Society for Pentecostal Studies, and National Council of Churches Faith & Order work that was groundbreaking, to his engagement with Korean churches and scholars.

Evangelical social justice activist and writer Ron Sider, who was for a time Don’s brother-in-law, described him as “a simply brilliant scholar with an incredible mind, who popularized his own research in an effective way.”

Don’s formative time at Houghton College (the Wheaton of the East) revealed to him what a fundamentalist college provided in the early 1960s with their tangible piety existing alongside intellectual engagement; his father’s mentor Stephen Paine was the college president and served as president of the National Association of Evangelicals from 1948-1950. Dayton’s father became president of Houghton with its mandatory chapel most days, a dress-code, and other traditional holiness practices.

Don was a dedicated institutionalist who questioned why institutions existed, from what historical movements they evolved, and how they functioned for those found at the margins of such organizations, schools and movements. Formed in the crucible of the Wesleyan tradition during America’s civil rights struggles, Dayton witnessed and chronicled the flow from and to the margins of religious life in America.

JoAnne Lyon, Ambassador and General Superintendent Emerita of the Wesleyan Church and vice president of the National Association of Evangelicals was instrumental in bringing back Don closer to the denominational fold in the later decades of his life, having felt estranged as a young man given differences in his developing theology. Lyon recalls, “I invited him to The Wesleyan Church General Conference in 2016 as a special guest. We did a night of recounting our heritage and how we are living it out today. He wrote me, ‘I nearly wept out loud tonight as I felt I can now embrace the church of my upbringing.’ I concurred.”

Dayton influenced, supported and mentored many women scholars and church leaders, especially those in the Wesleyan and holiness traditions. Lyon remembered, “Don and his then wife Lucille produced a paper for the Christian Holiness Association convention in 1974, Women in the Holiness Tradition, that was a Kairos moment in my life. I wept when I read the paper and the impact has continued throughout the years. May his voice continue down through the generations.”

Dayton’s work highlighted the fact that while “most people associate [women’s ordination] with ‘liberal’ churches … the fact is that the churches of the NAE (i.e. more marginal) ordained women a century before the churches of the NCC (i.e. more mainstream) and in much larger numbers until recently.” It was his style to point to a religious movement’s often inconvenient history to keep our eye on the Gospel for the disinherited, more than cultural ephemera which often moved us to focus on the powerful or those considered central in religious movements.

Dayton was involved in several ongoing conversations and debates across academic disciplines and areas of thought. Regarding historiography in his own discipline, he was known for a debate with historians George Marsden of Duke University and Mark Noll of Wheaton College on the roots and streams of fundamentalism. The question remained for him: how could one understand the evolution of fundamentalism into neo-evangelicalism focusing primarily or exclusively on the Reformed churches and not Wesleyan and holiness movements. His early scholarship took head on the previous assumptions that orthodox or traditional Christianity was not deeply connected to reform movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. From abolition and women’s movements to civil rights and other reforms, the followers of Jesus were front and center in Don’s retelling.

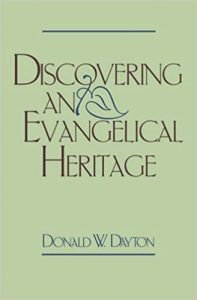

His experience of fundamentalism personally in the 1950s and 1960s, and its evolution into the religious right of the 1980s to the 2000s, was regularly chronicled by Dayton. He wrote in the 1988 Preface to one of his most important books, Discovering an Evangelical Heritage: “I do not entirely sympathize with the new religious right. I do think that we have something to learn from it — and that it needs a more sympathetic treatment than it tends to get from the secular media and from some other Christians.” By 2007, having just finished teaching at a school where, along with other holiness Christian colleges, he noticed they had returned to a new brand of fundamentalism, he remarked “I don’t think I really believed in the existence of the new religious right until at [my] university I met a mathematics professor researching the ‘biblical worldviews’ of the students and faculty. When I asked about themes of biblical worldviews, I was referred to The Federalist Papers.”

His experience of fundamentalism personally in the 1950s and 1960s, and its evolution into the religious right of the 1980s to the 2000s, was regularly chronicled by Dayton. He wrote in the 1988 Preface to one of his most important books, Discovering an Evangelical Heritage: “I do not entirely sympathize with the new religious right. I do think that we have something to learn from it — and that it needs a more sympathetic treatment than it tends to get from the secular media and from some other Christians.” By 2007, having just finished teaching at a school where, along with other holiness Christian colleges, he noticed they had returned to a new brand of fundamentalism, he remarked “I don’t think I really believed in the existence of the new religious right until at [my] university I met a mathematics professor researching the ‘biblical worldviews’ of the students and faculty. When I asked about themes of biblical worldviews, I was referred to The Federalist Papers.”

Dayton believed in the centripetal and centrifugal movements within evangelical movements (theology and practice move from the center to the margins, and from the margins to the center) which often perplexed participants who assumed a linear, one-dimensional movement from traditional to liberal. He helped his readers understand how seeing things “from the margins” revealed the constant motion of orthodox and heterodox thought and practice, revealing that history must not be told merely from one angle or direction.

Referring to his work with the World Council of Churches, he stated, “I had little luck convincing the Council that as one moves to the periphery one must also make theological adjustments to the more radical ecclesiologies found there. Global Christianity is much more than European Christianity in local dress.” He was blunt in asserting that in the ecumenical movement “it is clear that most wish to dialogue with those higher on the social ladder, better understood and studied, and more ancient and prestigious.”

Christianity Today co-founder Carl F.H. Henry, known to Don and others as part of the Chicago Declaration, was fond of telling a joke to many of us that exposed related tensions at the time. What’s the difference between an evangelical and a fundamentalist? The fundamentalist says to the evangelical, “I’ll call you a Christian if you’ll call me a scholar.” Dayton often found himself between these two camps and tried to help them understand their common and divergent roots, and just as importantly, possible futures.

His Ph.D. dissertation adviser and mine, University of Chicago historian Martin Marty, commented that Donald Dayton “in Walt Whitman’s term, ‘contained multitudes,’ so he is hard to condense. Dayton, in one of his essays, identified himself in the company of the ‘riff-raff’ whose roots had been, in the eyes of ecumenical elites, less than respectable. There were high-brow Methodists in the academy and the media, but he chose the low-brow route to make his contribution to scholarship in the rough-and-tumble circles of ‘holiness’ movements, and brought them into the religious spheres where ‘scholars of the heart’ found and find a home. I was his doctoral adviser and learned far more from him than I taught him.”

Our fellow Marty advisees included Vincent Harding, Nancy Hardesty, and Craig Barnes, each like Don with a distinct relationship to the social justice perspectives of Sojourners and served as leaders in the broader evangelical movement. Dayton pointed to the Fourfold Gospel tradition as being central to understanding what happens to such movements when they interacted with and sometimes clashed with more traditional approaches both to the practice and study of Christianity in America.

Dayton’s books are well known to those who study and teach Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism among American Christian movements. His students ranging from Scott Kisker, Dawk-Mahn Bae, and Myung Soo Park to Christian Collins Winn have gone on to publish and teach in the fields he first helped establish for and with them. In the festschrift created by Winn and fellow students, From the Margins, Dayton shines as a constant in a moving universe of interpretations of the various family members of Fundamentalism, Evangelicalism, Revivalism, Reform church, holiness, Charismatic, and Pentecostal movements. That these lesser known movements at the edges were acknowledged as part of the American Protestant family at all was his important contribution.

Dayton’s books are well known to those who study and teach Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism among American Christian movements. His students ranging from Scott Kisker, Dawk-Mahn Bae, and Myung Soo Park to Christian Collins Winn have gone on to publish and teach in the fields he first helped establish for and with them. In the festschrift created by Winn and fellow students, From the Margins, Dayton shines as a constant in a moving universe of interpretations of the various family members of Fundamentalism, Evangelicalism, Revivalism, Reform church, holiness, Charismatic, and Pentecostal movements. That these lesser known movements at the edges were acknowledged as part of the American Protestant family at all was his important contribution.

Internal coherence is something Dayton sought whether investigating German theologian Karl Barth’s work or attending to the Wesleyan church’s role in ecumenical dialogue. As his student Christian Winn elucidates, Dayton believed that the movements he explicated were themselves a powerful interpretive lens for those seeking a connection between the imperial Christian establishment in Europe and Asian Christianity among other two-thirds world churches. Dayton strongly believed that the study of holiness movements held clues to understanding evangelicalism and other related movements and churches.

How does one make sense of Dayton, who was taught by global theological giants Paul Ricoeur and David Tracy yet wrote as a Barthian from the Wesleyan tradition with a Yale education and studied holiness movements to help European ecumenists understand Korean evangelicals as part of the American Pentecostal and fundamentalist traditions? How should we understand this historical theologian in the Hans Frei narrative theology tradition whose understanding of third wave feminism arriving via 19th Century women’s reform movements moved him to interpret modern day race and poverty movements as deeply indebted to that same century’s struggles at Oberlin with Finney’s abolitionist movement among evangelicals?

The Reverend Dr. Hana Kim, pastor of one of the largest Presbyterian churches in the world, Myungsung in Seoul, Korea knew Dayton at Drew and saw him as a “scholar who swam upstream. His audacious yet poised findings shed lights upon the study of evangelicals and greatly aided seekers of American church history. He called for a moratorium on the use of the term ‘evangelicalism’ that led me to find the true meaning of it. His scholarship and legacies will be remembered not only in the US but also in many parts of the world including South Korea.”

Dayton clearly expressed that doing justice must come first and that would bring people closer to God and Jesus. Others with whom he dialogued felt that by attending to one’s faith in Jesus the justice would flow from that. Don was not convinced that piety led to social justice, or at least he was not willing to risk that and thus called for social justice to come first or be acknowledged as so integral that they could not be disentangled theologically.

The temptation to achieve political power and lose your evangelical soul appears to be too strong for many American (and other global) Christians about once every generation. Dayton wondered if the temptation to move to the center of power was too much to resist and thus action from the margins was the safest or most viable way to witness to Jesus’s good news.

Donald Dayton was an important theologian and historian, a rare intellectual who meshed together the “preferential option for the poor” with the hermeneutics of suspicion, explaining: “I have fought more to find ways to put my scholarship at the service of the poor. I have learned much from this strategy, but it is not to be recommended to the faint of heart.” His students, readers, and ecumenical activists continue to reveal his legacy and keep us on a path of appreciative interrogation across Christian movements.

Robert Wilson-Black is CEO of Sojourners. A graduate of the University of Chicago (Ph.D., A.M.) under Martin E. Marty, and the University of Richmond (B.A., M.H.), Rob served as a college and seminary vice president for 10 years before joining Sojourners in 2009.