VATICAN CITY (RNS) — One of the Vatican’s most important but least studied departments is actually one of its most extensive: the massive network of lay and religious people engaged in peacemaking, information gathering, and international diplomacy who throughout history have swayed governments and challenged kings.

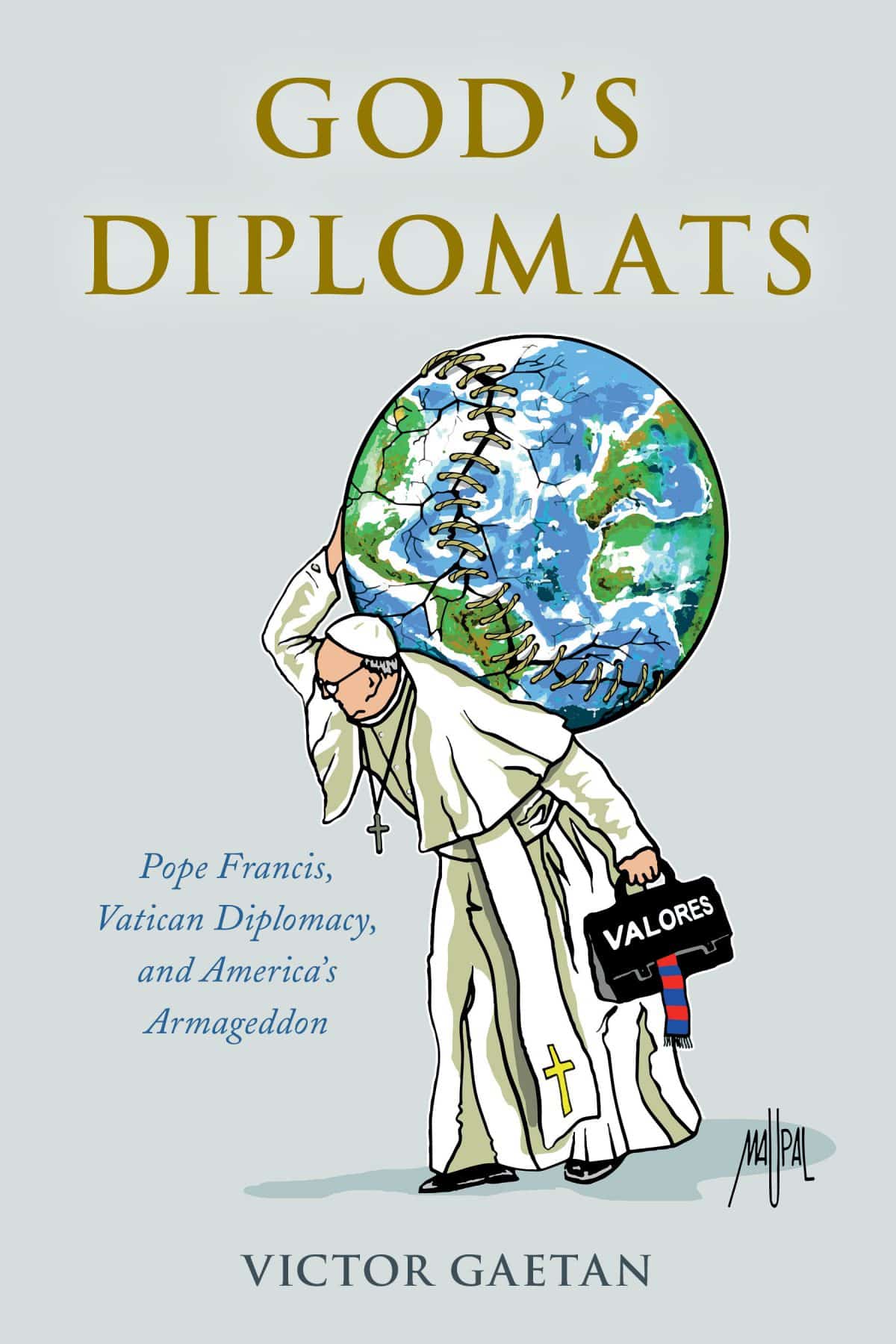

In a new book, God’s Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy and America’s Armageddon, journalist Victor Gaetan unveils the inner workings of the Holy See’s diplomatic efforts. The book not only corrects the relative anonymity of the Catholic Church’s crucial function, but also discloses how Vatican diplomats often find themselves clashing with United States foreign policy.

“As pope, Francis practices diplomacy for a multipolar world,” said Gaetan in an interview with Religion News Service. “In three major theaters today, the Holy See sees U.S. hubris as particularly counterproductive: Middle East, Russia and China.”

“And in each place, Francis goes out of his way to model dialogue as the antidote to conflict,” he said.

Rich in personal anecdotes and interviews, God’s Diplomats is divided into two parts. In the first part of the book, Gaetan unpacks what makes Vatican diplomacy effective and unique before taking up case studies in which cassocked diplomats have tipped the balance in favor of dialogue and encounter amid global crises.

An important and often confusing distinction underlies the book. Vatican City is an independent city-state, “smaller than Central Park,” as Gaetan puts it, while the Holy See is a global entity that reaches wherever its more than 1.2 billion faithful are.

“That duality is at the heart of what makes Vatican diplomacy nimble — and successful,” said Gaetan.

The Holy See’s top diplomat is the secretary of state, currently Cardinal Pietro Parolin, who holds a position comparable to that of prime minister. His office is divided in three parts, one for general church affairs, another for relations with other states and the third, created by Francis in 2017, comprises diplomatic staff.

The secretariat can count on a network of Catholic charitable organizations, lay movements, missionaries, and nuns spread across the world who have a direct insight into the communities they serve. In addition, it has a permanent observer status at the United Nations, allowing it to get “involved in the nitty-gritty of global debates,” Gaetan said.

Holy See representatives, called nuncios, cultivate relationships with most of the world’s governments, relying on information gathered by Catholics on the ground. They are trained at the oldest training institute for professional diplomats in the world, the Pontifical Academia Diplomatica, created in 1701.

Gaetan dissects a nuncios’ preparation, which includes international and diplomatic history, negotiation techniques and fluency in at least four languages. Historically, the author explains, Vatican diplomats applied principles of prudence and discretion, born from their experience in the confessional.

Francis has ordered the development of courses on the plight of immigrants and refugees, and aspiring Vatican diplomats must now undergo a mandatory year of missionary work. Like his predecessors, Francis asked a Catholic lay movement to help him forward his vision, the Catholic Movement of St. Egidio, which is centered on “prayer, poor, and peace.”

As a state without an army and with its biggest export being postcards, it can remain above the push and pull of economic and political power. Its charitable works further burnish its reputation. The pope’s diplomats are nonetheless powerful intermediaries on the world stage. If they are little recognized, it’s in part because they often prefer to work behind the scenes.

Under Francis, Vatican diplomats tipped the balance in favor of dialogue and negotiation from Kenya to Colombia to South Sudan and influenced a host of other issues.

“Did you know that under Pope Francis, Vatican diplomats have questioned the ethics of weaponized drones, challenged pharmaceutical companies for claiming intellectual property rights that prevent the poor from accessing medicine, and defended indigenous people losing land to extractive industries such as mining?” Gaetan asks in the book.

This pope and the United States have seen their positions drift farther apart, most recently disagreeing on China. But Gaetan explains that “the worldview clash between the U.S. and Holy See extends back to the start of the modern era” in 1870.

Pope Leo XIII “was horrified” by the U.S. takeover of the Philippines in 1899, Gaetan writes, just as Pope Benedict XV opposed the post-World War I Treaty of Versailles because it deepened resentment among the losing parties, especially Germany. After the U.S. dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Pope Pius XII was quick to diplomatically recognize Japan, angering President Roosevelt.

More recently, Pope John Paul II condemned the U.S. invasion of Iraq, while Benedict XVI’s rekindling of relations with Russia and the local Orthodox church angered the White House.

Questions remain as to whether Francis and President Joe Biden, the second Catholic American chief executive, see eye to eye.

“Can Biden impress on his foreign policy apparatus the need to settle disputes justly, without revenge, without seeking to “win” or to make another nation suffer for disagreeing?” Gaetan asks.

Gaetan points out that Biden helped his then-boss, President Barack Obama, decide to overthrow Libyan President Muammar al-Qaddafi, a move that Francis criticized.

“The catastrophic tragedy in Afghanistan should inspire reflection,” Gaetan told RNS, expressing his hope “that the president discerns the need for what Pope Francis counsels: identifying shared interests, even with protagonists. Then, working to expand collaboration from there.”

Gaetan explained. “Francis allies with national and regional stakeholders who have moral authority, whether they are political leaders or religious leaders,” he said. Francis has sought encounter in every major world crisis he has faced since the beginning of his papacy, Gaetan writes, sometimes angering political players as well as Catholics.

The U.S. is most at odds with the Holy See when it comes to Russia and China. When conflict arose in Ukraine in 2014, “the Holy See and Pope Francis refused to side with one party or the other in the conflict,” Gaetan writes. “They did not want a religious cold war to ensue in the country.”

Francis’s refusal to be sucked into the partisan conflict in Ukraine underlines how “the Vatican leadership believes Russia is a valuable ally for Europe,” Gaetan says. The same could be said about China. In 2018, the Holy See and China signed a controversial and secretive provisional agreement. Last year, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo all but chastised the pope for the deal during a visit to Rome.

Francis’s approach has yielded some landmark moments, from the historic encounter in 2016 at the airport in Cuba with Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill to the document on fraternity signed with the grand imam of al-Azhar, Ahmed al-Tayeb, one of Sunni Islam’s most esteemed leaders.

“The Catholic faithful mainly seem oblivious to the positive impact the Church has in the rough and tumble world of foreign relations, probably because so often the work is done behind the scenes,” said Gaetan, who said that writing the book has strengthened his own faith.

“But as one of the world’s last absolute monarchies, the pope doesn’t need affirmation or permission for his policies — except from God. And having practiced diplomacy for some 1,700 years, the Catholic Church will surely keep at it,” he added.