Note: This essay is a free issue of our e-newsletter A Public Witness. So, if you like it, please help sustain our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber to A Public Witness. You’ll receive more essays like this each week in your inbox (including this Thursday) and gain access to the full archive.

On Sunday, the congregation attending Influence Church in Orange County, California, heard two sermons. First up was preacher Josh Hotsenpiller, son of the cofounders of the megachurch. He started his sermon by noting he was actually supposed to speak second but guest speaker Larry Elder was running late. So, Hotsenpiller asked the congregation to “be here for God’s word, too.” Then he asked how many people were excited to hear from Larry Elder, and the congregation erupted with applause and cheers.

After Hotsenpiller finished his sermon, the praise team sang about raising “a hallelujah.” Then a staffer for “American Faith,” a political commentary site founded by Hotsenpiller’s dad, came to the stage to introduce Elder, one of the leading candidates for California’s recall gubernatorial election happening two days later (Sept. 14).

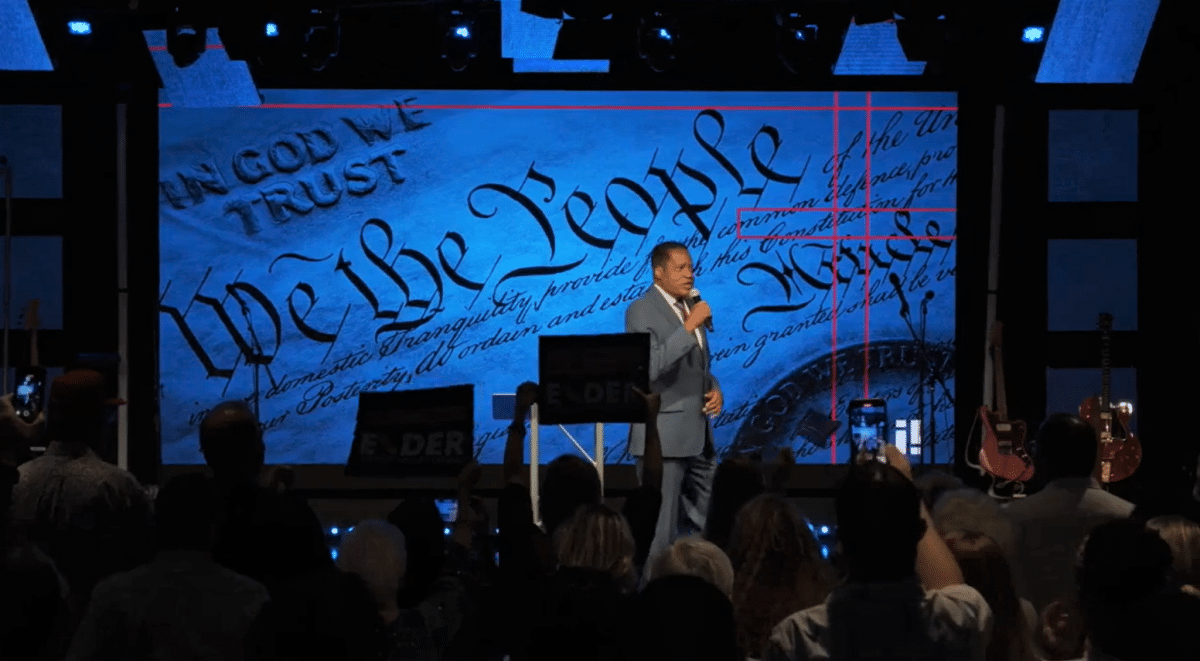

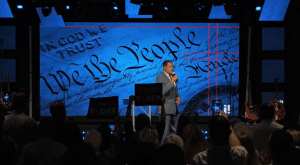

The large video background behind the pulpit changed from showing lyrics of a praise song to displaying the beginning of the U.S. Constitution. But stamped on top of the Constitution was “In God we trust” and the outline of a cross.

As the words on the church’s screen changed, so did the tone of the service. Elder quickly made it clear this “sermon” wouldn’t be about the Bible. He started his remarks by announcing, “I’m running for a number of reasons,” and proceeded to outline various political and economic complaints about Gov. Gavin Newsom.

If you closed your eyes, Elder’s remarks — and the crowd’s applause, cheers, and laughter — would’ve fit right in at a campaign rally in a rented gym or a park’s pavilion. But this secular, partisan speech occurred in a sanctuary during a church service on the Sabbath in a house of worship exempt from paying taxes. And if you opened your eyes, you would’ve seen people — purportedly there because of Jesus — waving Elder’s campaign signs as they cheered him on.

Screengrab of Larry Elder speaking at Influence Church on Sept. 12, 2021, as some near the front hold up Elder gubernatorial signs.

Sadly, this event wasn’t an anomaly. Rather it was a common occurrence in churches across the Golden State in recent weeks as Elder and other gubernatorial candidates seek political salvation at the ballot box. And it’s a problem that occurs during elections across the country.

In this issue of A Public Witness, we look at today’s special California election and the troubling campaign tactic of churches turning over their pulpits on Sundays for campaign speeches. We also offer a reminder that the IRS rule banning such partisan sermons has not been recalled.

Total Recall

Unless you are reading this in California, you are excused for not following this story more closely. The vitriol of last November, along with the vast misinformation and shocking insurrection it produced, linger in bitter-tasting ways. Many desire a reprieve from following politics. If we ever needed an “off-year” from elections, this would seem like it. But not everyone has been spared from another cycle of campaign ads.

One interesting facet of California election law is that citizens can band together to demand a vote on whether their elected leaders should continue in office. For only the second time in gubernatorial history, the recall effort succeeded in gathering enough signatures to put the question to a vote. The first time this happened was in 2003, when Arnold Schwarzenegger ended up being cast for a new role.

What prompted the current recall effort against Gov. Gavin Newsom, who Larry Elder railed against at the “church” service, is far from clear. The technical language of the petition listed a set of grievances around immigration, tax policy, water use, and even the death penalty. The actual outrage by his critics is less about these issues and more about his perceived hypocrisy and overreach in response to the pandemic.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom at the 2019 Democratic Party State Convention in San Francisco. (Gage Skidmore/Creative Commons)

The long odds against defeating Newson ensured political theater rather than actual policy debates would define this election. Dozens of candidates, including Caitlyn Jenner, qualified for the ballot, and Elder emerged as the frontrunner. A former lawyer, Elder’s fame stems from a long career writing books and hosting a conservative talk radio show. Controversies from new allegations of physical violence by a former fiancé and past claims of sexual harassment have tarnished his campaign.

Polls and pundits predict that when the polls close tonight and the ballots are tabulated, the governor will easily retain his office. Faced with this likely outcome, Elder and others are already alluding to election fraud as a way to excuse their inability to oust Newsom from office. The message of “rigged” elections may haunt our politics as the new normal. But regardless of the outcome of the recall election, we find much that alarms us in the campaign.

Political Blessing

Elder’s “sermon” on Sunday at Influence Church was merely another example of campaigns politicking during worship services. Alejandra Molina reported for Religion News Service about Elder’s Aug. 15 remarks during services at Calvary Chapel Chino Hills in San Bernardino County.

The church’s pastor, Jack Hibbs, is a vocal supporter of Donald Trump and attended the former president’s infamous Jan. 6 rally on the National Mall just before the insurrection at the Capitol. Hibbs blamed the violence that day not on its instigators and perpetrators but on the country for supposedly “eject[ing] God from the courts and from the schools.”

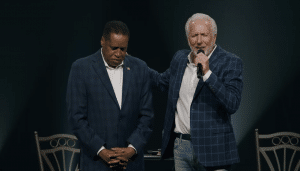

Hibbs, who continued holding indoor worship services last year in violation of Newsom’s COVID-19 restrictions on mass gatherings, also encouraged Elder to run in the recall election. And Elder told Hibbs’s congregation that he was running because “I have a spiritual, a moral, and patriotic obligation to do it.” Hibbs, who suggested during a worship service that people donate to Elder’s campaign, then laid hands on Elder and prayed for the election.

Reporter Faith E. Pinho of the L.A. Times covered Elder’s visit on Sept. 5 to Destiny Christian Church in Rocklin. Elder told the 5,000 people in the sanctuary — and the thousands more watching online — “People of faith, in my opinion, have stood on the sidelines for far too long. We need to get involved. And that is why I’m running.”

That church and its pastor, Greg Farrington, sparked headlines throughout the COVID-19 pandemic as they also defied Newsom’s state health orders banning indoor mass gatherings. Their services were later linked to an outbreak of the virus. More recently, Farrington spoke against COVID-19 vaccines as supposedly creating “a morally compromising situation for many people of faith,” so the church offers religious exemption letters for anyone seeking to avoid vaccination mandates at their workplace.

Farrington introduced Elder at the service by quoting Proverbs 29:2: “When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.” The pastor then added, “We’ve been groaning in the state of California for a while right now, because we have not been governed by a moral governor.”

Screengrab as Greg Farrington (right) prays for Larry Elder on Sept. 5, 2021 at Destiny Christian Church.

But Pinho pointed out in her report that Elder isn’t alone in this campaign strategy. That same Sunday, Newsom could be found in the Youngnak Church of L.A., a Korean American congregation, making his own faith-based pitch as he seeks political redemption: “The Bible teaches us we are many parts but one body. And when one part suffers, we all suffer. This notion of a web of mutuality — that we’re all in this together.”

Several other recall candidates have also tried this approach. Some pastors, presumably trying to follow the requirements of IRS rules, invited multiple candidates over various Sundays. They avoided making explicit references about how to vote and refrained from endorsing candidates. Others choose to completely ignore those lines.

At this past Sunday’s service at Influence Church (that we watched so you don’t have to), once Elder ended his stump speech, the ministry staffer who introduced the candidate then put a hand on Elder’s shoulder. He led the congregation to pray “in the name of Jesus” for God’s “blessing upon Larry and his team.” Then as Elder left the stage to applause, a pastor at the church walked on and declared, “Come on, Influence Church, can we please give it up for Mr. Larry Elder. Elder for governor.” She then urged people to give to the church to help them “be the influence.”

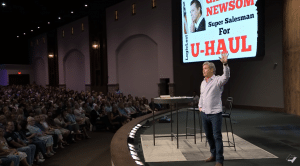

And like Farrington at Destiny, the staffer who introduced Elder at Influence made a point to highlight their opposition to Newsom as based, in part, on their disagreement with his COVID-19 mass gathering restrictions: “Last year, churches were deemed nonessential. We were essentially attempted to be shut down by the governor of California. And we learned firsthand the importance of righteous leadership.”

The implication was clear and explicit. Vote to recall Newsom, and then vote for Elder as governor. And do it as an act of worship to protect your church.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Totally Destroy

These appearances by candidates during church services might win some votes. The pastor may bank a favor or two with a powerful person. Yet, it puts the church at significant risk, legally and spiritually.

Partisan activities by 501(c)3 tax-exempt nonprofit organizations are prohibited through what is called the “political campaign activity ban.” You might recognize the rule from its informal nickname: the “Johnson Amendment.” That reference is to then-Senator Lyndon Johnson who proposed it in 1954. Some conservatives use the moniker to paint it as a liberal policy even though it was passed without controversy by a Republican House and Senate and then signed into law by Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower. It was later strengthened in 1987 by a Democratic House, Republican Senate, and Republican President Ronald Reagan.

According to IRS guidelines on the political campaign activity ban, a nonprofit improperly engages in partisan politicking if they do not give “an equal opportunity to participate to political candidates seeking the same office.” In other words, a nonprofit must invite all (or no) candidates from the various parties to speak.

The IRS also notes an organization could invite a candidate to speak in “a non-candidate capacity,” but that should occur without references to the election or candidacy. Factors that would determine if a nonprofit improperly engaged in partisan politics include “whether either the individual or any representative of the organization makes any mention of his or her candidacy or the election” or “whether the organization clearly indicates the capacity in which the candidate is appearing and does not mention the individual’s political candidacy or the upcoming election in the communications announcing the candidate’s attendance at the event.” The Sunday services we noted from the California recall campaign clearly violate these restrictions.

President Donald Trump promised in 2017 to “totally destroy the Johnson Amendment.” Despite falsely bragging about ending the prohibition, an executive order he signed only instructed the IRS not to enforce it.

President Trump signs an executive order pausing IRS enforcement of the political campaign activity ban during the National Day of Prayer event at the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, D.C., on May 4, 2017. (Carlos Barria/Reuters)

Undoing the ban would require congressional action, which has repeatedly failed. BJC and Americans United for Separation of Church and State in 2017 and 2018 led a coalition to push back legislative attempts to repeal the ban. More than 100 faith groups and more than 5,600 nonprofits signed on to support the ban. (Note: We covered more of the history and purpose of the political activity ban in an award-winning podcast episode back in 2018.)

Despite the widespread support from religious groups in support of the Johnson Amendment, it is widely ignored by both Republicans and Democrats. Not only did Trump campaign at churches during the last campaign but so did Joe Biden and several other Democratic hopefuls.

Yet, only one church so far actually lost its tax-exempt status under the rule. But it wasn’t for what happened in its sanctuary. A church in New York ran into trouble after it paid for newspaper ads attacking Bill Clinton during the 1992 campaign. Others have been investigated but not punished, including a liberal Episcopal church in California after a sermon during the 2004 campaign.

And while the IRS generally remains reticent to investigate houses of worship — likely for reasons of underfunding as well as concerns about not wanting to be cast as anti-religious — this rule still applies to houses of worship and other 501(c)3 tax-exempt nonprofits. Since Trump didn’t actually get rid of it, that means inviting a candidate to come speak about an election puts a church at risk of an IRS investigation or worse. Just because the IRS hasn’t often enforced the rule in the past doesn’t mean it couldn’t start today.

All to say, Hibbs, Farrington, and others should be praying there aren’t any IRS agents in their congregations.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Beyond the IRS

Imagine, though, that the IRS’s ban on political campaign activity didn’t exist (i.e. Donald Trump’s dreams actually come true!). In this scenario, churches would be allowed to become partisan weapons in our political fights, but that doesn’t mean they should. The sacredness of our worship space brings a far more significant reason to avoid the practice. Pulpits should not be turned over to politicians for electoral gain.

As Amanda Tyler of BJC explained in the December 2017 issue of Word&Way magazine, she is “very concerned about what [eliminating the Johnson Amendment] could do to the character of nonprofits and to our reputation in the communities” as 501(c)(3) organizations have not “been sullied by partisan campaigning like just about every other section of our society has.” The California recall suggests that Tyler is too optimistic about the damage already done, but we agree that even more harm would be inflicted if Congress repealed the ban.

Our witness as the Church is more important than who sits in the Governor’s Mansion in Sacramento or even in the Oval Office. When a church endorses a candidate, it sends a message to people who support a different candidate that they aren’t really welcome. And when a church turns over the pulpit during worship for a campaign rally, we reduce the words from God to just another human voice competing for attention in the public square.

“We cherish our role as separate from the State, and that prophetic voice that the Church can serve to the State on issues,” Tyler added back in 2017. “Pastors and people of faith know that there’s nothing free about a pulpit that is bought and paid for by political campaign donations or beholden to partisan interests.”

Screengrab of Jack Hibbs preaching at Calvary Chapel Chino Hills on Aug. 15, 2021, just before Larry Elder joined him on stage. On the screen in the sanctuary behind Hibbs is a satirical anti-Newsom ad.

Many of the pastors preaching the gospel of Larry Elder claim that Gov. Newsom took away their religious freedom during the COVID-19 pandemic. As much as we disagree with them on the substance of the argument, their cries for liberty ring a bit ironic as their actions reveal their fascination with temporal power. Tying their reputations to a politician or a party taints their sacred calling and settles for a much lesser prize. Whether Elder finds victory or defeat, these churches have already lost.

Returning to what transpired at Influence Church on Sunday, the congregation was inadvertently given a warning in the sermon preached before Elder arrived. That preacher, whose name you may recall is Josh Hotsenpiller, read from Luke 9: “What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, and yet lose or forfeit their very self?”

What good is it, indeed?

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood