(RNS) — Over the course of the past two years, the preachers of the Washington National Cathedral have addressed the grief, loneliness, and other trials of the COVID-19 pandemic through sermons each Sunday. Now, a new book, Reconciliation, Healing, and Hope: Sermons From Washington National Cathedral, has compiled dozens of their homilies about facing the realities of illness and isolation.

Its editor and provost of the cathedral, Rev. Jan Naylor Cope, said that every Sunday since the cathedral reopened in July — except for a brief closure at Christmastime during the height of the omicron variant — visiting worshipers have arrived early to express their gratitude for the virtual sermons and services offered throughout the pandemic.

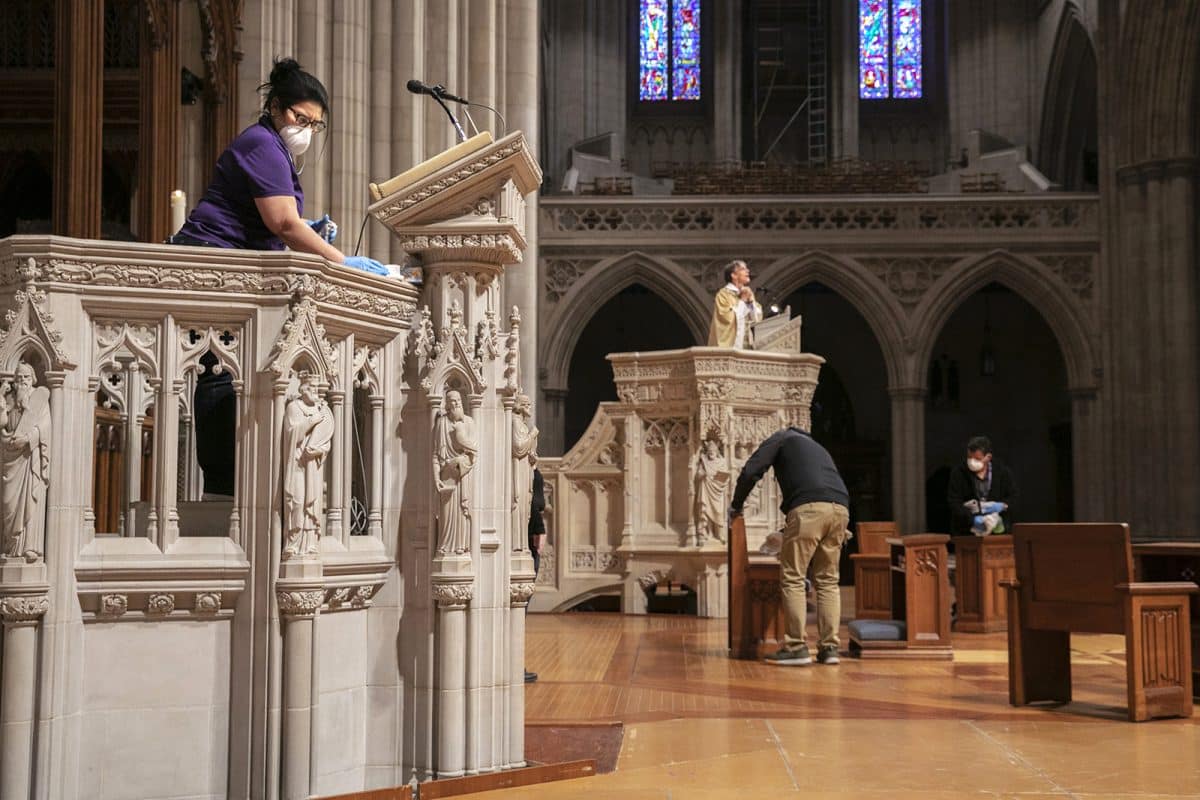

Wearing a face mask, Erlinda Ortega (top left) cleans a pulpit, while Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde (center) with the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, prepares to record a homily, after Budde led Easter Sunday services via livestream to an empty Washington National Cathedral on April 12, 2020, in Washington, D.C. (Jacquelyn Martin/Associated Press)

“People who’ve been worshiping with us online started coming, making a pilgrimage, because they just wanted to meet us, to thank us in person,” said Cope, who is among the 10 preachers featured in the book that includes two bishops, six cathedral staff clergy, a canon theologian, and a canon historian.

“It tells me that people need God and something to be hopeful about. And people in this pandemic need connection. People have been so isolated, alone, afraid. They just need to connect,” she explained.

Cope, who oversees the cathedral’s development department, spoke with Religion News Service about the cathedral’s expanded online congregation, the way it adapted Communion, and the enduring lessons of pandemic preaching.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Two years after Washington National Cathedral halted in-person services due to the pandemic, what has been the most surprising result for the preachers from the cathedral’s pulpit?

Just the overwhelming response from people, literally all across the country and around the globe, who found us during the pandemic and have wanted to be in relationship with us.

You already had an online presence before the pandemic so how did it change?

We might have a few hundred people or so streaming live with our service and then maybe during the course of a week, 1,500 people or so would pick up the service. Today, even after all the other churches have reopened — so this is not peak during the pandemic, but two years in — we’ll have four or five thousand people streaming live, and by the end of the week, (a two-year average of) 34,000 will have watched the service. So you can see the dramatic increase.

Many of the sermons, especially early on, directly mentioned the pandemic, either the grief of loss of life or of normalcy, or the appreciation of streaming technology. At some point, was it no longer cited because it had become a new norm?

It was still cited but some other events happened, like George Floyd’s murder, and we knew we were dealing with not only the pandemic of COVID-19 but the pandemic of systemic racism, and we felt we needed to speak to both.

These cathedral sermons dealt with loving others, including across partisan lines, or, as you just mentioned, fighting racism in light of the protests after George Floyd’s murder. What difference can sermons make on such challenging topics?

I hope that what we’re lifting up is the power of love. And what unites us is stronger than what divides us. Our (Episcopal Church) presiding bishop, Michael Curry, says it best and most succinctly: that the way of Jesus is the way of love. And we are trying to lift up, as Christians, that Jesus was a reconciler. He was a uniter, not a divider. And also during that time, of course, we’re going through a presidential campaign and election. The divisiveness of that on top of the others just made it essential that we speak to bringing people together and lifting up common values and ethics in the midst of pretty challenging times.

On Easter of 2020, Bishop Curry noted that the smells of lilies were missing but Easter came anyway. Have Easter observances been some of the most difficult times during the pandemic?

Yes. Particularly that first Easter. We were limited with the number of people who could physically be in the space. So I was not at the cathedral. Most of the clergy were not. The dean and our bishop were and it was the first Easter I could remember in my life that I hadn’t been in church, and I just wept. All of us did. Was it hard? Yes, it was incredibly hard. That first Holy Week, I’ll never forget preaching Maundy Thursday, which was a very personal sermon, to a camera on a tripod.

Cathedral Dean Randy Hollerith preached that “Christ will appear wherever his followers gather together to break bread,” even “when we are gathered as a digital community.” How did the cathedral adapt Communion during the pandemic when you didn’t have an in-person congregation?

None of us received. So we offered up during the time of Communion a prayer for spiritual communion. The people online, as well as those of us who were in worship, were not physically receiving Communion. The first time we offered Communion was Easter ’21. And we called it drive-by Communion because we weren’t gathered yet. But people were so longing that we masked up, we put on gloves and people literally drove by. There was a couple who drove up from North Carolina, who had been worshiping with us. People came from all over and all they were going to do was see us for just a moment.

Were you serving bread and wine?

No. We’re still not serving wine. It’s bread only.

Washington Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde preached on love being “more than a feeling.” Though she talked about following Jesus, she also encouraged people to recommit to their community of faith as a way to experience “loving well.” Do you have a sense of how much of an interfaith audience the cathedral has had online?

That’s harder for me to say. It’s much more ecumenical than it is interreligious, although you never know who’s out there. I was preaching and I happened to quote Jewish New Testament scholar Amy-Jill Levine in my sermon. I got back to my office and had an email from Amy-Jill Levine, whom I did not know. And she said something to the effect of thanks for the shoutout.

You mentioned in a sermon shortly after Easter last year that many people have reached out to the cathedral seeking a national service of grief around COVID. What is the cathedral’s response to that request?

You mentioned in a sermon shortly after Easter last year that many people have reached out to the cathedral seeking a national service of grief around COVID. What is the cathedral’s response to that request?

We’re still in it. When we’re asked to do a national service, like after 9/11, 9/11 was a specific event. Will we do something for a million lives lost? Probably. But that’s one reason why we continue once a month our Saturday COVID memorial services where we read the new names that have come in, and lift (them) up. That’s why at the 100,000; 200,000; 900,000 mark, we’ve tolled our Bourdon bell because something has to mark these moments. And we can’t forget. It’s imperative that we remember: 1,500 people are dying a day. So when people were pressing us, we understand why, because people wanted it to be over. We wanted to put a punctuation point in it, but we’re not there.

You titled the book you edited Reconciliation, Healing, and Hope. What lessons have you learned about any of those topics that may shape your sermons in the future?

We are wounded, all of us in some way. And Jesus was a great healer. That was one of the things that first attracted people to him. It’s still true that we are called to be repairers of the breach, to be healers, to be reconcilers. Our faith points us to the hope that is always there if we have eyes to see and ears to hear and hearts to respond. That’s the core of our Christian belief. And so our work is never done.